Energy transition: An emerging speciality

Kerogen Capital is trying to plot a more nuanced course into energy transition than building renewables. It is one of a growing number of nascent specialists in the space.

Ten years ago, Kerogen Capital was deploying its debut energy fund of around USD 1bn. The Hong Kong-based firm – formed through two spinouts, first from J.P. Morgan, then from Ancora Capital – targeted upstream oil and gas, typically assets too small or complex to interest global energy giants. It sought to feed the appetite of Asia's national oil companies that needed resources to fuel growth.

Today, Kerogen is pivoting. To the extent oil and gas remain part of the strategy, they will likely be addressed on a deal-by-deal basis. The firm is back in the market seeking USD 1bn, but for a global decarbonisation and sustainability investment platform, leveraging its experience in traditional energy to accelerate the transition to new sources.

It is a path trodden by numerous US oil and gas investors – spurred not only by the decarbonisation opportunity but also by a recognition that LP interest in energy is at best bifurcating, with some abandoning assets perceived as dirty. The most common solution is to recruit a renewables team.

Kerogen is taking a broader view that encompasses clean power, renewable fuels and chemicals, energy storage and battery ecosystems, and the decarbonisation of traditional energy. To this end, it absorbed Cobalt Equity Partners, an industrials-focused manager that spun out from General Electric. Cobalt is intended to provide downstream capabilities that complement Kerogen's upstream savvy.

"We didn't want to go down the typical renewables route. We needed to be more fundamental: energy transition touches every industry and business model. Moreover, the returns generated by onshore solar and wind had compressed dramatically," said Jason Cheng, co-founder and CEO of Kerogen and CEO of the new strategy, CelerateX.

"Energy transition 2.0 is not just 1.0 on steroids, it needs a complete rethink of the investment landscape. When we looked at the skillsets required to be successful, we realised we would benefit from adding coverage in areas like manufacturing, aviation and other industrial sectors. That's why we approached Cobalt."

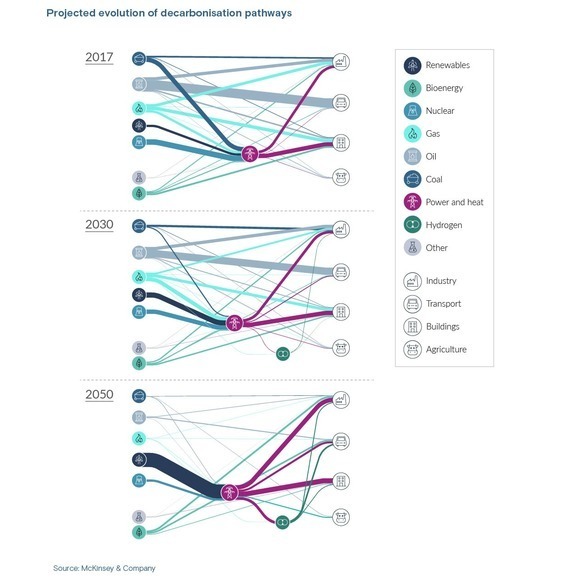

Achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050 – seen as essential to keeping global warming to no more than 1.5 degrees Centigrade – requires USD 275trn in capital spending on physical assets for energy and land-use systems, according to McKinsey & Company. Plenty of investors are looking for ways to tap into projected annual average spending between 2021 and 2050 of USD 9.2trn.

Oil and gas converts are among the more conspicuous members of a global energy transition financing ecosystem that features investment funds, utilities, banks, and other lenders. "The fastest energy transition underway is that of oil and gas professionals' business cards," Scott Jacobs, CEO and co-founder of US-based sustainable infrastructure investor Generate Capital, wryly observed.

But he welcomes the additional competition: "There are lots of sources of talent focused on how to get more sustainability solutions in the world, including talent from the traditional fossil fuels space. We need more human capital and financial capital to address the problems we are talking about."

Divergent strategies?

Generate's strategy involves targeting a segment below the classic large-scale wind and solar projects characterised by large equity cheques, long-term contracted cash flows, low risk, and low returns. It tends to focus on smaller opportunities, using technology to address inefficiencies, and delivering infrastructure-as-a-service that is more closely aligned with evolving customer needs.

The firm has been around for 10 years and claims to engage with assets before they enter the infrastructure mainstream. Sustainable power exposure includes green hydrogen, geothermal, fuel cells, and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, as well as solar and storage.

Other dedicated energy transition investors eke out their better-than-core-infrastructure returns by operating at different points along the risk curve. For US-based Energy Capital Partners (ECP), the goal is to deliver a mid to high-teens IRR by acquiring yield-generating power generation assets and then adding storage capacity or reconfiguring them to extend the operational lifespan.

Kerogen pursued PE-style returns from oil and gas, and CelerateX will do the same in energy transition. The willingness to address complexity is still there. For example, offshore wind is of interest because the team can leverage the fact that the technologies currently used to keep wind turbines afloat – barges, spars, and semisubmersibles – served much the same purpose for oil rigs.

Even as energy transition strategies take off globally, CelerateX remains an anomaly in Asia. The only specialist of comparable size is Decarbonization Partners, a joint effort between Singapore's Temasek Holdings and BlackRock with USD 600m in committed capital. Others tend to be sub-USD 250m in fund size and more geared towards climate technology, often with a global mandate.

"There is so much more depth in Europe than in Asia. We've talked to people about raising a fund and there are only a couple of managers in the space and one of them does quite a lot of investment in sustainable foods," said Toby Chan, co-founder and a partner at Audacy Ventures, which is currently investing its own capital. Chan previously worked for Kerogen.

"We see some people transitioning from traditional venture capital, but they would likely invest in businesses with more of a software component because they don't know enough about energy or the hard-tech side. There are a lot of carbon-tracking app deals."

Audacy has invested in areas such as sustainable aviation fuel, carbon capture and storage (CCS), and hydrogen fuels. There are similarities to Virescent Ventures, which spun out last year from Australia's Clean Energy Finance Corporation and is raising a AUD 200m (USD 133m) fund. Energy is the largest component of a strategy that also includes mobility, food and agriculture, and the circular economy.

Singapore-based Trirec closed its second fund last year on USD 100m. One of the founders, Melvyn Yeo, was the first investor in Sunseap, a solar developer sold to EDP Renewables at a valuation of USD 816m in 2021; his co-founder set up Sunseap. The strategy is early stage, but Yeo stresses the firm's comfort with capital-intensive businesses. Fund I had reasonable upstream energy exposure.

The biggest energy transition bets by private equity investors in Asia to date have come from generalist GPs. Biofuels have featured prominently in the past 12 months, with Hahn & Company's USD 292m carve-out of a recycling-enabled biofuels division from SK Chemicals and Bain Capital investing USD 400m in Hong Kong's EcoCeres. (Kerogen backed EcoCeres a year earlier.)

Other large investments reach deep into the renewables space, but Doug Kimmelman, founder and a senior partner at ECP, observes there is always an element of risk when GPs step outside their traditional comfort zone. This is especially the case when managers become operators.

"The kiss of death is when someone says, ‘I don't do merchant risk because I do renewables.' What happens when your plant is down for mechanical or weather reasons, and you buy replacement power? That's merchant risk. What happens when your contract goes below 10 years, you go to sell it, and the buyer evaluates the forward curve to set a price? That's merchant risk," said Kimmelman.

Three journeys

There is a prototype for the CelerateX strategy pursued by Kerogen. Norway-based HitecVision was established in the 1980s as a drilling and oil services player before raising its first institutional PE fund in 2002. Fund VII closed on USD 1.9bn in 2014. Five years later, it pivoted to decarbonisation, targeting renewables, CCS, alternative fuels, and helping traditional energy move to low carbon.

These investments first featured in HitecVision's 2019-vintage fund of USD 658m, according to a source close to the situation. It is now marked at 3.1x and distributions exceed 1x. HitecVision New Energy Fund – a debut energy transition vehicle – closed on EUR 875m (USD 947m) in 2022 and the scale-up is expected to continue. The firm didn't respond to requests for comment.

Kerogen's evolution has also been gradual. The Fund I thesis of targeting emerging basins and hard-to-access oil and gas deposits with a view to tapping Asian national oil companies to support development waned as these companies scaled back their M&A. For Fund II, which closed on USD 830m in 2016, the focus switched to operational improvement investments in the North Sea.

Spending time in Europe brought Kerogen closer to markets that were more attuned to environment, social, and governance (ESG) protocols, more stringent on emissions reporting, and more advanced in discussions that would ultimately lead to net-zero commitments. In 2016, the firm developed a carbon-light investment strategy for oil and gas, which ruled out tar sands and carbon venting.

Deeper exploration of energy transition 2.0 led to Kerogen announcing a formal commitment to the strategy in 2020. A net-zero pledge – including a 50% reduction in carbon intensity at the portfolio level by 2030 – came the following year. By this point, Kerogen's two largest portfolio companies, Zennor Petroleum in the UK and Pandion Energy in Norway, had achieved carbon neutrality.

"When we announced net zero, we were amongst the first managers in PE to do so. It required explaining the implications," said Cheng. "By and large, our LPs were positive. Given our background in real assets, LPs already appreciated we had strong experience in managing ESG factors."

In addition, elements of energy transition were already creeping into the portfolio through floating offshore wind, geothermal energy, and the digitalisation of energy.

The Cobalt acquisition represented the culmination of a different journey. Mark Chen assumed the leadership of GE's Asia Pacific private equity business in 2005 and took an operations-heavy approach, leveraging the parent's industrial connections and insights. Investments included Nanjing Gear, an industrial gearbox manufacturer that was repositioned to supply wind turbines.

The Asia PE unit was among the last to be offloaded as GE exited its voluminous financial services portfolio. Chen and his team opted to spinout as an independent – a three-year process during which he was counselled by Cheng, a friend as well as a professional acquaintance, and a spinout veteran.

Cobalt launched a fund, targeting around USD 300m, and signed up anchor investors. Progress was thwarted by tensions within the LP base and an unhelpful clause that allowed one LP to block any investment, according to a source close to the situation. After two years of work, the team decided to unwind the structure. Cheng then proposed merging Cobalt into Kerogen.

"They already had the geological and technical teams, and they knew the upstream inside out. Geothermal was a natural segue. Biofuels – perfect; because it's basically a refinery-type business. Offshore wind – perfect; because a lot of it stems from offshore oil and gas," said Chen.

Cobalt will bring its own experience to bear in areas like electric vehicles and energy storage, but the ultimate objective is a triangulation of ideas. In sustainable aviation fuels, for instance, Kerogen would examine an opportunity through a refining and chemicals lens and Cobalt would approach it from an engine manufacturer and aviation customer's perspective.

Domain expertise

Energy transition has been tapping traditional energy skillsets for years; not just technology, but also the regulatory and financial systems that govern energy and the supply chains that serve it. "Everything we do is rooted in something that's been done before. It can be hard to transition because so much capital stock is already meeting customer needs," said Jacobs of Generate.

One of the parallels Jacobs draws is between geothermal engineering and conventional drilling. Carlos Araque, co-founder and CEO of geothermal energy start-up Quaise, has experienced this first-hand. He spent 15 years in the oil and gas industry before switching to investment in 2013 and receiving a funding pitch from researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The technology, which emerged from MIT's plasma science fusion centre, involves taking a gyrotron typically used heat plasmas in nuclear fusion experiments and turning it into a boring machine. Drilling to a depth of 20 metres with a device capable of heating hydrogen to millions of degrees Centigrade can evaporate the target rock and generate geothermal heat.

"You could be anywhere in the world, and provided you drill deep enough, you are guaranteed access to that heat. We are talking about 300 degrees. Even in Iceland, geothermal heat is no more than 200 degrees, which isn't hot enough to serve industrial use cases," said Araque.

He decided to join the company instead of funding it. Quaise will soon begin field demonstrations of its technology, with commercialisation expected by the end of the decade. The plan is to drill close to established fossil fuel power plants, utilising existing infrastructure and replacing the energy source. A total of USD 75m has been raised to date, mostly of from VCs such as US-based Xplorer Capital.

The fingerprints of traditional energy are also visible in Cool Planet Technologies, a CCS start-up in the UK backed by Audacy. The founders, who have an oil and gas background, convinced a German research institute that its gas separation membrane technology could be applied to carbon dioxide. Then they launched pilot projects involving coal power plants and a Holcim Group cement plant.

"They used their engineering expertise to pack membranes into the carbon capture plants because they understand how gases react to different conditions," said Chan of Audacy. "They are also familiar with North Sea caverns where oil has been extracted and carbon can be stored."

Quaise and Cool Planet have yet to reach a level of development that would make them relevant to later-stage investors, but they demonstrate how the convergence of energy transition and traditional energy is also a convergence with technology. This became apparent to Kerogen when Pandion in Norway rolled out a digitalisation platform, prompting research into broader applications.

"We started looking at the impact of technology on time, productivity, and safety," said Cheng. "In the US, people were already developing analytical models based on the data sets coming out of US shale and using digital twins and robotics to improve uptime and productivity. It was applicable across our entire portfolio. We knew we had to introduce digital technology when building new assets."

Kerogen and Pandion ended up working with Google on a sub-surface search engine capable of analysing 200 wells a day – 100 times the capacity of an analogue system. The private equity firm went so far as to relocate a team member to Silicon Valley to track emerging innovations that might be additive to the existing portfolio or new energy transition-related investments.

Time and place

Given that convergence is playing out against a backdrop of massive expansion, the challenge is knowing how to apply skillsets. Jacobs of Generate describes an energy ecosystem that is ever more distributed, decarbonised, decentralised, and democratised. While noting the link between old and new energy, he adds there are "at least as many differences as there are similarities."

For example, under energy transition, distribution can literally work backwards. Electricity networks were designed on the premise of centralised production and one-directional flow to the point of consumption. The rollout of rooftop solar has confounded that presumption.

"About 20% of houses in Australia have rooftop solar, and nearly all export power some of the time. We're not far from the time when 40% of all substations on the Australian grid will experience reverse flows," said Blair Pritchard, a partner at Virescent. "Renewable energy is highly distributed and highly variable, and we have to lift our game to cope with that."

For ECP, the priority has always been reliability. Kimmelman ranks affordability and security ahead of decarbonisation from a customer perspective. Energy transition involves changing where electrons come from and supplying them in larger volumes because electrification – from transportation to digital infrastructure to power consumption – is becoming more widespread.

"You need to manage the input and output and there's risk because electricity markets can be volatile, and we are replacing baseload coal and nuclear in the US with intermittent renewables. The underlying product can't be stored, and batteries are 1% of the market," Kimmelman added.

Private equity firms will decide the best mode of application according to their investment mandates and expertise. The other consideration is time. Energy transition is broad enough in scope and the need is large enough in scale to create growth opportunities for everyone – provided they don't move too early (pre-empting provability) or too late (missing out on the highest returns).

Chen of Cobalt (and now CelerateX) recalls GE resisting the urge to enter wind energy for 15 years before finally extracting a ready-made business from the carcass of Enron in 2002. Within five years, it was of significant scale; within 15, it was a key standalone division.

"There are things we see as a generation past, like land-based wind, which have become too established, too commoditised. And there are areas we think are a generation too early such as hydrogen where the infrastructure isn't there," he said. "Over the next two to three decades, there won't be a better opportunity set anywhere than in energy transition, but timing is everything."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.