Asset allocation: So long, silo?

The total portfolio approach remains on the margins of asset management. Advocates of the model hope LPs will reconsider as they look for alpha beyond the areas where they normally find it

Brookfield Asset Management's A$4.38 billion ($3.17 billion) acquisition of Australian hospital chain Healthscope, which closed last year, was a private equity deal from a private equity fund underwritten to a private equity return. When Healthscope's freehold hospital properties were separated from its operating business, a Brookfield real estate fund could have participated in the deal, a source familiar with the firm admits. However, a couple of North American real estate investment trusts were willing to pay more.

Later in 2019, the alternative asset manager moved for another Australian business, paying A$1.95 billion for retirement home operator Aveo Group. Once again, the target generated revenue streams from properties as well as services, but in Brookfield's view, it skewed more towards the former. The deal was allocated to the real estate strategy. Meanwhile, the firm's infrastructure funds continue to accumulate data centers, though other investors would classify them as real estate.

Healthcare, aged care, and information and communications technology infrastructure. Three megatrends underpinned by unyielding realities – Asia is getting richer, older, and increasingly reliant on data – but to some extent, they defy traditional asset class designations. If GPs are becoming more flexible in how they target these areas, factoring in operational upside, cost of capital, and investment tenor, should LPs review the rigid allocation parameters to which they are harnessed?

The strategic asset allocation (SAA) versus total portfolio approach (TPA, also known as the one portfolio approach) debate is not a new one. But amid the seemingly inexorable shift from public to private markets – institutional investors are running out of other places to pursue alpha – and the concentration of capital in areas such as healthcare and technology, it could be argued that thinking about exposure in terms of theme rather than silo represents a more prudent approach to risk.

"The biggest headache for CIOs is generating a 7-8% net return now that cash is zero, stocks that have done well are overpriced, and bond returns are heading south, and do it without loading up on risk assets in a way that doesn't work," says Marcus Simpson, formerly global head of private capital at Australia's QIC. "People have traditionally started with 70-30 or 80-20 equity-bond portfolios. Maybe that isn't right going forward, given the return expectations. At the same time, people are asking what they are really trying to get from their portfolios, what do they want to access."

On the move

Few industry participants would dispute the growing popularity of private markets or the primary reason behind it – low interest rates dragging down returns in other asset classes. There are two caveats: tweaking asset allocation is like turning a supertanker; and some tankers turn faster than others, with a subset barely able to turn at all. Still, Richard Tan, head of private markets for Asia at Mercer, believes the returns issue will only intensify. "The alternative is alternatives," he says.

There is even a case to be made that COVID-19 will accelerate this transition. Ferdinand von Sydow, a managing director at HQ Capital, who primarily focuses on Germany, notes that some investors reduced their public equities exposure as markets plummeted in February and March, tried to get back in a month or so later, but couldn't because prices had recovered. They ended up under-allocated. "It has made people understand the importance of private equity as an asset class that is stable, with no moving in and out," von Sydow says.

Comparisons are drawn with where institutional investors found themselves in 2008-2009 and it's possible that alpha will be found in similar places. Back then, Steve Byrom, who now runs institutional advisory firm Potentum Partners, was head of private equity at Future Fund. Confronted by so many unknowns and looking to get as much diversification as possible, the Australian sovereign wealth fund turned to private equity, and specifically idiosyncratic growth.

Byrom is doing the same now, through a broadband spectrum deal: it is virtually uncorrelated to listed equities and has a small negative correlation to listed real estate. Growth is expected to persist regardless of what happens in the wider economy. The same could be said of various other assets that fall into the gaps between infrastructure, real estate, and private equity.

However, increasing exposure to private markets or thinking more carefully about how that exposure is calibrated is several steps removed from abandoning SAA – which might be akin to taking a supertanker back to the dry dock for a refit.

Any investor contemplating changes within the private markets space has many more strategies to choose from. Ten-plus years ago, from a global perspective, private equity was buyout, venture, and a smattering of growth. Dedicated healthcare sector funds were relatively few. Banks had yet to step away from lending, so there was no void for private debt providers to occupy and deliver attractive risk-adjusted returns in an area where investors are currently having trouble finding yield.

If anything, says Brian Gildea, head of investments at Hamilton Lane, silos within private markets are disappearing as strategies proliferate. If an LP wants access to private credit, venture, small buyout and healthcare, these exposures should be mapped out to avoid having too many relationships that are similar in nature. Meanwhile, manager selection is not necessarily any easier.

"Investors are thinking holistically about what they are doing – they are not putting private markets to one side and letting it do its own thing," Gildea adds. "Private markets are becoming more mainstream – allocations might be 5% today but they are increasing to upwards of 20%, and some endowments are above that. That's one of the reasons why data and transparency are so critical. You can feed information into your system in real-time and understand your risk exposure and how it is moving."

Others agree that they get enough diversification through SAA that there is no need to take a different approach, deliberately thematic or otherwise.

"We've found that the range of asset classes we invest in – public equities, fixed income, private equity, infrastructure, private credit, absolute return, real estate, and risk parity – are broad enough in their respective purviews that we are able the be thematic and opportunistic within this framework. In other words, it would be unusual and unexpected for our staff to conclude a given opportunity is appealing but that it couldn't be mapped to one of these areas," says Marcus Frampton, CIO of Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation.

The counterargument, made by Simpson, is that having a portfolio tilt more towards venture and healthcare isn't enough. He expects overtly thematic approaches to become more prevalent, perhaps with overlay guide points around environment, social, and governance (ESG) agendas.

Head to head

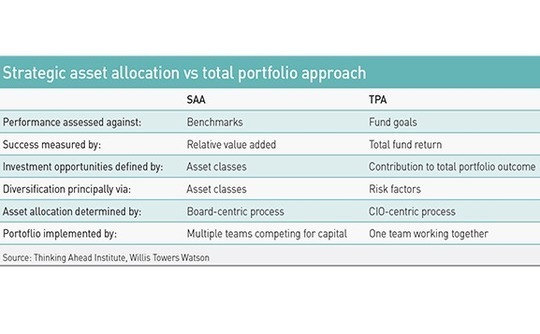

On a basic level, TPA is distinct from SAA in several ways. Performance is assessed via overarching fund goals, success is a function of total fund return, and strategies are implemented by the entire team working together; investment opportunities are defined by their contribution to total portfolio outcome; and diversification is based on risk exposure. With SAA, silos are the starting point. Individual asset classes are judged using specific benchmarks and the value they add relative to other asset classes. Teams compete for capital allocations, silo against silo.

"It is a governance challenge to have a structure that allows you to not really care which bucket an asset falls into and just look at the validity of the asset on its own idiosyncratic perspective. When we manage portfolios, we have a real assets team rather than separate real estate and infrastructure teams. We want people researching together. We want as many eyes on an idea as possible," says Craig Baker, global CIO at Willis Towers Watson, which advises investors on TPA and uses the model to manage some of its discretionary capital.

While Washington University makes familiar claims about breaking down silos and turning every investment professional into a generalist, several industry participants do not consider AustralianSuper to be particularly advanced on the one portfolio journey.

There is evidence of a movement beyond traditional silos: investment coverage is broadly divided into mid-risk, such as infrastructure, property and credit; traditional fixed interest; and equities, which serves as a catch-all for almost everything else. There is an emphasis on forming agile, cross-asset-class teams, with listed equity analysts contributing sector knowledge when private equity opportunities are being assessed. "We can look at anything and know we'll have a home for it, if it's a good deal," Shaun Manuell, a senior portfolio manager at AustralianSuper, told AVCJ last year.

Manuell is part of a single equities team, which is agnostic on public versus private, giving it the flexibility to pursue opportunities that cut across both. Another LP drills down to the philosophy behind the strategy: "Is it a question of do I do this through the public market or the private market, rather than am I getting a better risk-adjusted return by doing this as a credit investment over any another type of investment? And does that make it an extended equities silo rather than total portfolio?"

Within Asia Pacific, GIC and NZ Super stand out for using reference portfolios as the foundation for TPA. Sitting below its reference portfolio – currently 65% global equities and 35% global bonds, based on long-term risk appetite – GIC has a policy portfolio that offers balanced exposure across different asset classes and an active portfolio charged with pursuing skill-based strategies that bring alpha to the policy portfolio while broadly maintaining the same level of risk.

NZ Super also uses the reference portfolio – 80% equities, 20% fixed income – to achieve a basic level of diversification and then an actual portfolio that incorporates more specific asset classes based on whether they can improve the portfolio by increasing the return or reducing the risk. The sovereign wealth fund also engages in strategic tilting, responding to opportunities created by near-term market dislocation if they are consistent with longer-term thematic goals.

Hamilton Lane's Gildea notes that asset classes like private equity do not feature in any large tactical shifts in an overall portfolio because implementation takes too long and so the window of opportunity would pass.

Money and ideas

TPA is supposed to serve as a melting pot for top-down themes and bottom-up ideas. At Willis Towers Watson, the top-down perspective comes from the asset research team, which develops views on economies, considers the implications of those views for markets, and thinks about how to access the ideas that come out. The bottom-up is investment managers whose job is to identify strong partners in the asset management community and in doing so get exposure to other ideas.

"We blend all of those things and think about risk across various lenses – there is a specific mandate for each portfolio we run as to how much risk we should be taking – and there are tools that help us structure portfolios along those lines," Baker explains. "An enormous amount of quantitative analysis goes into it, but ultimately it's a qualitative judgment."

NZ Super takes a similar approach, but David Iverson, the group's head of asset allocation, observes that the top-down element might be stronger than most. For example, the merits of a proposed 5% allocation to retirement real estate would be examined and then an asset allocation team member will consult with relevant individuals across the organization before entry points are chosen.

Future Fund, on the other hand, is more bottom-up oriented. There is no reference portfolio as a starting point and its strategic themes are deliberately broad. According to Byrom, who played a key role in creating Future Fund's private equity strategy and led the team through 2018, this made competition for capital even more intense. Once a fortnight the investment committee met and the bottom-ups – representatives of different strategies – pitched their best ideas.

"It requires a high level of communication and a culture whereby it's acceptable to turn around and say ‘I don't have any great opportunities right now' or ‘I don't think we should be investing in my sector right now.' That's incredibly hard to do if it means you're going to lose allocation," Byrom says. "But we would have robust debates about which opportunities were best for the portfolio as a whole, not for a certain sector."

Once a decision was taken, the different teams – incentivized to pursue the best outcome for the fund – pulled together on execution. In areas like healthcare and logistics, infrastructure and private equity specialists would work side-by-side on deals. Byrom recalls one situation where infrastructure and credit were targeting the same asset, from an equity and a second lien credit angle, respectively. The investment committee decided to go with credit, and the teams collaborated on it.

In adopting TPA, Future Fund was greatly advantaged by the fact that it was starting from scratch in 2007. There were no existing asset class silos to tear down. An investment team could be assembled that possessed skills relevant to the model and foreknowledge as to what they were getting into. Compensation schemes didn't have to be restructured to reinforce the sense of common purpose.

NZ Super introduced its reference portfolio in 2010 while the actual portfolio and tilting elements were formalized a few years later. Compensation was already based on whole fund performance, though Iverson admits that the investor's recruitment philosophy "did gravitate towards generalists, because specialists often see what they want to see." He maintains that shift in mindset among those raised under an SAA system is the biggest challenge.

TCorp, a financial markets partner for the New South Wales government with A$107 billion in assets under management, is a more recent convert, having spent the last three years reorienting internal operations to incorporate TPA. In part, this involved organizing the entire investment staff along skill or function lines, rather than by asset class.

"Mechanically it is not that hard, but culturally it is very difficult," Stewart Brentnall, CIO of TCorp, said in a discussion with Willis Towers Watson in March. "It is a cultural journey. You can't just design a good process and give everyone an instruction manual; it needs a cultural change."

Size isn't necessarily an impediment. Washington is among the top 20 US university endowments but its $8.5 billion in assets are about one fifth those of Harvard. NZ Super's TPA journey began 10 years ago when it had NZ$15.6 billion ($10 billion) under management. Indeed, Byrom notes that the larger Future Fund's team got, the harder executing the strategy became. Keeping everyone informed all the time proved challenging.

Nevertheless, most of the clients Willis Towers Watson advises on implementing TPA have scale. The rest can always delegate fiduciary management to a third party, setting return targets, risk paraments and a timescale, and request TPA-style exposure.

Irvine of NZ Super contends that TPA is tied to investor size because of a tendency to conflate changes in portfolio construction with LPs taking more asset classes in-house, especially private markets where they must pay up for talent. The two phenomena, though distinct, are related. If a desire to capture alpha in the voids between asset classes is one motivating factor behind TPA, then the arrival of a more mature phase of management, best characterized by internalization, is another. An asset owner responsible for every part of a portfolio is more likely to view it as a single entity.

Championing change

At the same time, TPA is not the only way to pursue a thematic strategy. To take it to one extreme, endowments and foundations – arguably the antithesis of TPA in terms of diversification and flexibility – might claim to be thematic. As one investment professional puts it: "We focus on two themes: innovation, broadly defined, which is why we are 50% VC; and the consumer-technology opportunity in emerging markets, which is why we are 42% emerging and frontier markets."

Institutional investors will plot new courses in asset allocation – or fervently stick to tried and tested methodologies – based on considerations such as remit, regulation, resources, and risk appetite. The ongoing search for alpha suggests that private markets will play a significant role. And this will present increasing levels of complexity as investors work their way through a lengthy list of options.

These changing dynamics will prompt some groups to view their exposure to different asset classes in a more holistic way, which in turn may lead to a more formal reexamination of allocation strategy. Regardless of whether this is a version of TPA or not, the TPA experience underscores how significant shifts in approach require buy-in at all levels of an organization, from the top down. This is brought up repeatedly by LPs of all types.

It was true of Future Fund when David Neal, the first CIO, received very broad instructions to formulate an investment model. Just as it was true of San Francisco Employees' Retirement System (SFERS) in 2014 when it started transitioning to an asset-allocation approach more akin to an endowment than a public pension fund, heavy on venture and innovation. One source familiar with the SFERS credits the group's CIO for tirelessly advocating reform.

This is especially important if change involves fostering collaboration between representatives of different strategies or asset classes. Simpson recalls trying to put together a multi-asset-class approach during the fallout from the global financial crisis, targeting distressed assets with aspects of real estate, infrastructure, and private equity-style operating businesses. It wasn't that interest in the idea was lacking, rather those involved kept getting called away.

"Deals would crop up in their own asset classes and we couldn't get anywhere," he says. "If you are a vice president in the fixed income group and you want to get noticed by your boss and you are pulled into a side project working with people from across the organization on a thesis that isn't necessarily proven and for which the capital isn't necessarily there, you might want to just stay in your original team."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.