Asia exits: Liquidity lags

Private equity exits – outside of the public markets – are gradually emerging from a COVID-19 hibernation. But sellers must be mindful of timing, structure, and which buyers they are targeting

The Dow Jones Industrial Average has recovered nearly all the value it lost during February and March and is trading near to record highs. From Sydney to Tokyo to Seoul to Shanghai to Hong Kong to Mumbai, the stories may not be quite as spectacular, but they follow a similar theme: public markets defying the macroeconomic logic of lockdowns.

For private equity and venture capital investors, now is the time to lock in paper gains before the market turns, while simultaneously guiding a new generation of companies to IPO. Nearly $30 billion has been raised from 173 PE-backed offerings in Asia so far this year, according to AVCJ Research. This compares to $41.2 billion from 175 IPOs across the full 12 months of 2019.

"This year has been good for us in terms of exits. There's a pipeline of companies that have gone public in the past two years, so GPs are taking advantage of the strong market to lock in some gains," says Yar-Ping Soo, a partner at Adams Street Partners. "The IPO pipeline is also good, especially in healthcare. Once the lock-up on these companies expires, more distributions will come. We expect the high level of distributions to continue."

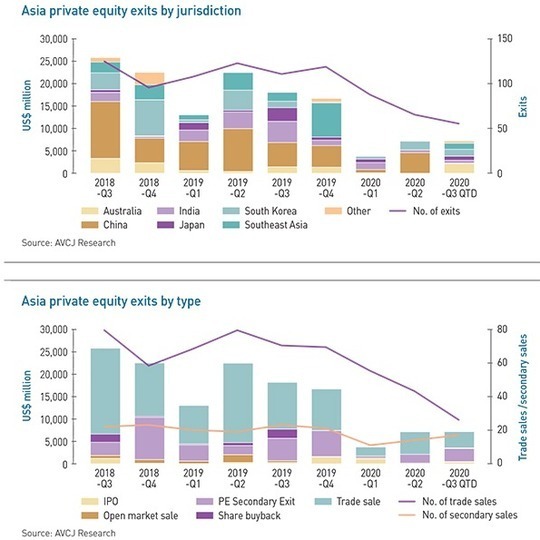

Overall exits, however, remain resolutely low. In the final three months of 2019, private equity firms generated $16.6 billion, roughly in line with the recent historical quarterly average. Trade sales accounted for 55% of the proceeds. COVID-19 forced strategic buyers to reexamine their economic models, causing numerous processes to be abandoned. Exits reached $3.7 billion in the first quarter of 2020, the lowest since the global financial crisis. Trade sales contributed $2 billion.

With travel restrictions preventing many prospective buyers from visiting targets – and continued economic uncertainty an obstacle for those who do have access – the situation has barely improved. Trade sales were responsible for $5 billion out of $7.1 billion in exits in the second quarter and $3.6 billion out of $7.2 billion so far in the third. The absolute number of sales has slipped from 69 to 55 to 43 over the past three quarters and stands at 26 in the current one.

There is anecdotal evidence from multiple advisors that the tide is finally turning. BDA Partners, for example, reported a relatively less active March and April, but saw business start to ramp up from May. The focal points are markets that have so far coped with COVID-19 most effectively: China, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam. Much of the work is pitching for mandates and preparing to launch new deals or transactions that were pulled earlier in the year and are now being reactivated.

"Everyone has internalized the fact that we aren't going back to normal. This is how we are all going to be interacting over the next 6-12 months, so if you want to be active you need to find a way to get things done with the restrictions that COVID-19 throws up," says Paul DiGiacomo, a senior managing director at BDA. "We are broadly optimistic about M&A activity, but especially private equity exit activity, and I definitely wouldn't have told you that in April."

Remote resources

The major obstacle to completing deals is the inability to conduct on-the-ground due diligence. A quick scan of the 10 largest trade sales from the coronavirus period suggests as much: seven went to domestic buyers and two went to other financial sponsors.

The 10th – and largest at $1.2 billion – saw US-based Kimberly-Clark acquire personal care products manufacturer Softex Indonesia from the family owner and CVC Capital Partners. Industry participants point to this transaction as an example of a buyer being lined up well in advance, having a degree of familiarity with the business through its own operations, and having probably conducted some on-site due diligence prior to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Buyers are increasingly willing to compromise on certain aspects of due diligence. In the absence of in-person interaction, videoconferencing, virtual site tours, and relying on trusted third-party advisors for verification are becoming more prominent aspects of processes. Levels of comfort vary: if the deal value is embedded largely in a single facility or operation, a visit might be mandatory; if there is a long tail of assets, it is easier and perhaps more practical to outsource physical inspections.

"Initially, we were quite skeptical about buyer interest during this period, especially for relatively larger transactions. We expected that buyers would need to meet management teams in person and do onsite due diligence," says Choon Hong Tan, CIO of Southeast Asia-focused Northstar Group. "What we are seeing is that, where buyers are familiar with the assets class and have a high level of conviction, they are open to virtual management meetings and using local service providers who can perform the due diligence without having to travel."

Although processes that stalled due to COVID-19 are now being relaunched, some private equity firms remain wary. Jason Shin, a managing partner at Korea-based VIG Partners, claims he would be happy putting a domestic-oriented business up for sale because there is reasonable confidence in the outlook – anything tied to global cycles is more problematic – and there is demand among local strategics for the right assets. But there is some discomfort at the notion of a full auction.

"Our assets are smaller and more oriented towards domestic than international buyers. We tend to do limited auctions or private transactions. If I were holding a very public, global auction, where you if you don't get it executed there is a stigma attached to the business, I think I would delay for a bit," he says. "I would wait for more visibility and certainty before putting it out there in a public fashion."

Issues around certainty and proximity might explain the tendency to go for smaller processes with known counterparties. While engaging and educating prospective buyers ahead of a formal auction has become standard practice in private equity exits – especially when dealing with strategic players that might require years to get their heads around a deal compared to months for financial sponsors – familiarity can pay dividends in a COVID-19 world.

"A lot of the deals we have seen recently are situations where people had existing relationships with management; maybe it is through different companies that were connected to those management teams or they have longstanding relationships with team members. They get comfortable without having managing directors going over to talk to them personally," says Marcia Ellis, a partner and co-head of Asia private equity at Morrison & Foerster.

When relaunching a process, it is logical to target groups that were involved the first time around and might have already conducted some level of due diligence. For new deals, there is an emphasis on buyers with a local presence.

"What we now pay attention to that we didn't as much before is who has boots on the ground, and who has had previous engagement with the company," says BDA's DiGiacomo. "Even if you don't have a local team, you might have spent some time getting to know the company pre-COVID and had face-to-face interaction and visited the facilities. It is much harder if you have never met the company before and you have no one on the ground who could satisfy that requirement."

Levels of comfort

A local presence doesn't necessitate a local buyer. Multinationals often have sufficient senior staff in China – who are now able to travel freely in-country – to make head office comfortable signing off on an acquisition. It is harder in markets like Southeast Asia, where the executives could be sitting in Singapore and the assets are elsewhere in the region. Even then, a Japanese or Korean strategic might be able to proceed on a Vietnam deal based on their experience in that specific market.

Modern Star, a primarily Australia-focused educational resources provider with a China expansion business, is an interesting example of how the geographical dynamics can change.

Navis Capital Partners put the business up for sale last autumn and lined up an international buyer that wanted to use the cash flows from Australia to support growth in China. This buyer expressed reservations in January when China's childcare centers and schools closed, so the process was halted. The GP then initiated a sale of the Australia operation alone in response to inbound inquiries from local investors, but that too was abandoned when the pandemic hit Australia.

By July, Modern Star had demonstrated robustness in the face of COVID-19 – when sales of school products were down, sales of toys and home products went up – and the Australian buyers reengaged. Navis ended up selling the company to Pacific Equity Partners for A$600 million ($433 million) earlier this month. It still owns the China business and several international buyers that were previously looking at Modern Star as a China expansion play have expressed an interest in it.

The switch from strategic to private equity buyer isn't surprising. While AVCJ Research's records thus far show little indication of an upturn in trade sales as 2020 has progressed, sales to financial sponsors rose from $436 million in the first quarter to $1.9 billion in the second and $2.9 billion in the third to mid-September. The number of transactions has increased as well.

Andrew Thompson, head of Asia Pacific private equity at KPMG, states that PE firms are quick to appreciate they cannot allow restrictions around COVID-19 to impair business for a protracted period and changing risk tolerance and approach is one way of breaking through that. In contrast, strategic investors, which may have to address internal issues before thinking about M&A, are generally more risk-averse and slower to adapt.

"They have to convince more stakeholders that it will be okay – convince them that it's still a good deal and that the process can change. And then they must get the board and c-level executives comfortable with doing it differently," he explains. "Some mid-level executives might have never met the founding family and they want to do the deal completely virtually. But when it works its way up to the board, they want to wait a year. There will be more secondaries as a consequence."

The pace of adaptation will vary by investor – Thompson estimates that strategics are generally 6-12 months behind their private equity peers – but some degree of change is seen as inevitable. Rodney Muse, a managing partner at Navis, describes it as an evolution through several phases: buyers having to be in the same location as their targets; remote buyers who previously visited and engaged with the target; and remote buyers who intimately aware of targets, but only as competitors.

"The final phase is people buying businesses that look interesting, that get through due diligence, but they've never visited and never had the opportunity to visit, and they've never met with management," he says. "We're not there yet but I'm hoping solutions to this pandemic will overtake the requirement for people to get there."

Navis, which also sold Malaysian IT business Strateq to Singapore's StarHub during the pandemic, is currently in negotiations regarding other assets with buyers from the likes of Japan, North America, and Europe. They all have some presence in Asia, but Navis tends to deal directly with headquarters. Muse notes that these local executives might be competitors – so he doesn't want them doing due diligence – or the deal will likely alter their circumstances, to they are deliberately kept in the dark.

Getting creative

Prevailing circumstances have also forced PE firms to be more creative in how they structure transactions. According to Samson Lo, head of Asia M&A at UBS, some vendors are reactivating deals and reconnecting with groups that expressed interest the first time around, but a 100% stake is no longer for sale. Rather, GPs have reined in their expectations and are looking to sell a significant minority interest now with a view to completing a full exit when the outlook is less volatile.

"You know that whoever buys 40% would be in pole position to buy the rest of the company later this year or next year, so it's not a bad way to get a deal done," Lo says. "It's not just an Asian phenomenon – I've seen a few global examples of 100% going to minority [stakeholders]. It meets liquidity requirements and allows you to take money off the table, while establishing a valuation benchmark. It is better than not doing anything at all."

Another solution – but perhaps more of a longer-term fix given the current uncertainty over valuations – is rolling over assets into continuation vehicles that give LPs the option of an exit as new investors give the same manager more runway with the assets.

K.C. Kung, founder of China-focused buyout firm Nexus Point is one of several industry participants who points to the secondaries as evidence of how avenues for monetization have proliferated. However, he also observes that for certain assets, the valuation gap is wider than before COVID-19. Buyers are calling for discounts on pre-coronavirus prices in recognition of the market uncertainty, while sellers expect a premium for businesses that have performed well during the pandemic.

DiGiacomo of BDA asserts that no one is selling based on the full impact of the pandemic year-to-date; rather assessments are based on look-through to run-rate performance, true underlying performance, or forward performance. And across the region in general, there are few examples of distress sales in industries that have been badly hit. Banks are willing to wait it out – or amid prolonged negotiations with borrowers – and private equity firms are reconciling themselves to playing the long game on problem assets.

"We want GPs to continue to show liquidity for our portfolio, but having said that, I don't think any LP would be willing to take a huge discount to get that liquidity," says Soo of Adams Street. "We are already seeing good liquidity and that buys GPs time."

If distributions are the price of patience, then managers who are unable to sell down positions in listed businesses must find other ways to generate some. This amounts to an incentive to push forward on trade sales. While attractive assets might go for a premium, several advisors observe that sellers looking for "crazy valuations" pre-COVID-19 are now willing to compromise. For private equity firms, numerous strategic considerations come into play, such as how much work an asset requires, the overall health of their portfolio, and their near-term fundraising plans.

"Putting aside exceptional companies that have done well through COVID, in a number of cases we have lost a year at least. I don't think there is any getting away from the fact that passage of time hurts IRR. It reinforces why, if we can lock in good IRRs from some of those positive ones we can, should and will do so," says Muse of Navis.

Reassuring recaps

Meanwhile, the private equity firm is further seeking to contain the impact of delayed exits by recapping stronger businesses that are not yet ready for realization and making dividend distributions to LPs. This is a standard maneuver from the Navis playbook: buy a company using a minimal amount of leverage; figure out a way forward, which usually involves investing in expansion; and once cashflow stabilizes take out some equity by introducing more debt.

However, Muse stresses the strategic importance of making these moves in the current climate almost as a demonstration of portfolio robustness. "It speaks to the strength of the business and the strength of the balance sheet," he maintains.

Others recognize the logic but are taking a more conservative approach, although much depends on how aggressive they were on debt financing in the first place. VIG has penciled in recaps for the first half of next year, with Shin noting that it will be easier to negotiate with banks when equipped with the full audited financial statements for 2020 rather than unaudited numbers for just six months.

A contrarian view is now might be the perfect time to engage with banks on refinancing. Many are carrying loans secured against businesses where covenants have been breached and the outlook is uncertain, but there is a reluctance to take punitive action. These lenders are naturally restricted when it comes to building new relationships, which means it is easier to persuade credit committees to expand exposure to proven borrowers that have emerged from COVID-19 relatively unscathed.

"That makes it quite fertile for dividend recaps," observes KMPG's Thompson. "Outside of Australia, the capital structures are more conservative and debt facilities are lower, so it's a fair conversation. You say, ‘We want to gear the business up, we've got an existing relationship, you've seen our financials and we've managed fine through COVID-19 and we are through the worst of it anyway, so how about we take that 3x to 6x and get some money out?'"

Northstar offered an added twist, securing one of the largest realizations of the pandemic period from an investment that was primarily structured as debt. In 2015, a consortium led by the private equity firm provided $1 billion in financing to Indonesian conglomerate Salim Group, whose founder pledged shares in several assets, among them Indomaret, the country's largest convenience store operator.

Taking advantage of the plentiful liquidity in the market, the deal has been refinanced, with a larger debt package replacing most of the equity. The investors received nearly $1 billion and retain a small stake in Indomaret. Salim secured more time to pursue growth initiatives, while Northstar – which is currently in the market with its fifth fund – took some money off the table.

"It's a win-win outcome, with Northstar returning a lot of capital to investors," says a source familiar with the transaction.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.