India e-commerce: Turning a page

The acquisition of Flipkart by Walmart signals the beginning of a new chapter in India’s e-commerce story. Venture capital investors also hope it represents a model for more exits from technology start-ups

India's e-commerce market can be a cutthroat place, as Kothandaram Vaitheeswaran knows firsthand. The entrepreneur and author helped establish the industry in 1999 with the launch of online music retailer Fabmart. He then headed the company through an expansion into more consumer goods categories and a rebranding as Indiaplaza before winding up the business in 2013 due to insufficient funds.

The experience gives Vaitheeswaran a unique perspective on the recent announcement by US retail giant Walmart that it would purchase Indian online marketplace Flipkart at a valuation of $20 billion. While acknowledging the success it represents for Flipkart's founders and investors, he worries about the effect this eye-popping number will have on Indian entrepreneurs.

"The exit is likely to convey to young entrepreneurs who are starting up that the way to build a business is actually not to worry about sustainability or profit, but simply raise money, spend it to create valuation, and hope somebody will buy them out," Vaitheeswaran says. "I would be very worried if Indian entrepreneurs look at this deal and say that's the way to go."

These misgivings are not widespread in the VC community. While no one disputes the fact that Flipkart has pursued scale at the expense of profitability, the successful exit from one of the country's unicorns is seen as a major validation of the Indian investment thesis. But they also recognize that the deal shows how far local start-ups need to go in some regards, particularly in comparison with their peers in China.

War of attrition

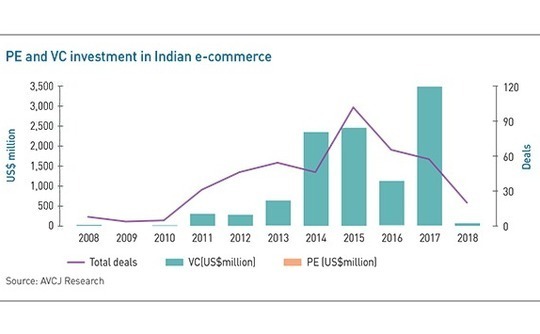

When Walmart announced it would pay $16 billion for a 77% stake in Flipkart earlier this month the news capped a long and sometimes tumultuous path for the company. Founded in 2007 by Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal, Flipkart had attracted multiple funding rounds from investors such as Accel Partners, Tiger Global Management, and Naspers. They wanted exposure to an e-commerce market that was experiencing rapid growth due to rising incomes and a surge in smart phone penetration.

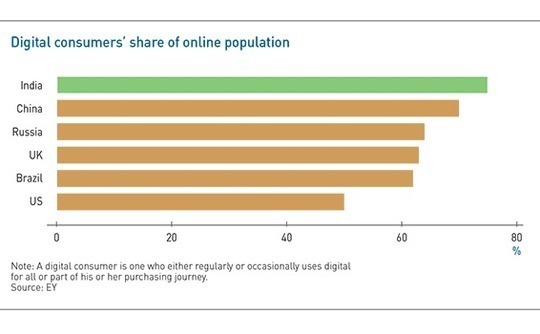

These predictions have been borne out. A report by the India Brand Equity Foundation last year found that the e-commerce market had grown from $7 billion in 2014 to $17 billion in 2017. It is predicted to be worth $188 billion by 2025. The same report showed that online retail represented just 2.5% of the country's total retail market in 2016, indicating considerable potential for growth in the customer base.

Flipkart was not the only company to recognize this opportunity, and it has fought for market share since inception. At first its battle was with domestic peer Snapdeal, US giant Amazon, and Paytm, a local online payment solutions and marketplace operator that is aligned with China's Alibaba Group. Three rivals became two last year as Snapdeal faded, but the competition was no less intense.

Flipkart's long war has been trying for its investors at times, particularly during 2016, the middle of an 18-month period when the company changed CEO twice and several other senior executives departed. During this period Amazon also overtook Flipkart and Snapdeal in gross merchandise value (GMV) for the first time.

With Snapdeal struggling, it was proposed that Flipkart absorb the business. SoftBank – a major investor in Snapdeal that subsequently bought a stake in Flipkart, which it will exit to Walmart – was the primary agitator for a deal. The breakdown in merger negotiations was greeted with condemnation by Snapdeal's other backers. Vani Kola, a managing director at Kalaari Capital, said the move would "harm the credibility" of India's start-up ecosystem.

Walmart's purchase took on added significance for VC investors given the turbulent history of both the company and the broader e-commerce market. The fact that Flipkart weathered these blows, kept on fighting and ultimately delivered an exit for its investors is seen as a vindication for the company's leadership and employees. More than that, the Walmart deal could help to sooth longstanding concerns about liquidity in India.

"As somebody who's been watching this space for a long time I'm very happy, but I'm actually more relieved than happy," says Sanjeev Krishan, India private equity leader with PwC. "Obviously there's been some discussion about how some of these bets have performed for investors – it's not as if you are finding a needle in a haystack, but clearly there have been fewer success stories in India than in other markets."

M&A outlook

VC investors recognize the deal as a confirmation that global technology players are willing to pay significant amounts for Indian technology start-ups. However, this represents only a part of the Flipkart exit's importance to the investment community. Further implications, including the impact on other VC-backed companies as well as on general entrepreneurial attitudes, will take longer to play out.

Though the sale generated substantial windfalls for Flipkart's investors, the clear majority of VC commitments in Indian e-commerce are in much smaller companies. For backers of these start-ups, many of which are pursuing niche markets such as jewelry or furniture, the question now is how the newly established competitive dynamics between three overseas companies – Walmart, Amazon and Alibaba, the latter acting through Paytm – will affect their own exit prospects.

"All three of these companies will do whatever it takes to keep growing market share," says Rahul Chowdhri, co-founder of Stellaris Venture Partners. "For the smaller e-commerce players this is a good thing: the larger companies will have this question of build versus buy, and now there are three well-funded players, so you will see more acquisitions."

Even before the Walmart deal Flipkart had dabbled in M&A with the acquisition of online fashion retailer Myntra Designs in 2014. Myntra has since become one of the platform's trademark brands, strengthening its footprint with the purchase of Jabong, another rival, last year. Amazon has made consolidation plays as well, buying online payment platform Emvantage in 2016 in a deal aimed at improving its own payment infrastructure.

Both companies have also made minority investments in several other Indian technology start-ups with a view to accumulating knowledge and industry partners. Flipkart has participated in multiple funding rounds for online truck booking platform BlackBuck as part of efforts to build closer ties with the logistics industry. In addition, it has supported Mech Mocha Game Studios and home rental platform Nestaway Technologies in the hope of collaborating on new technologies.

For its part, Amazon has made commitments this year to online insurance broker Acko, which is developing insurance products intended for online retailers and their customers. It also backed online lender Capital Float in order to improve credit penetration in India.

However, so far these investments have not represented a significant exit route for VC investors. Industry observers acknowledge this shortfall but believe the situation will change soon. Now that Flipkart, like Amazon and Paytm, has the backing of a large pool of overseas capital, it can step up its M&A activity to add capabilities it does not have, thereby attracting more customers. Rivals will have no choice but to follow suit, which will bring renewed energy to the overall market.

A useful template?

The usefulness of Flipkart as a model for other Indian start-ups is another topic of interest for GPs. Some worry that the community will emphasize the positive aspects of the story – the exit and its valuation – while downplaying the years of work it took to get the company to that point. In addition, focusing too much on a single success means founders will be ill-equipped to cope with a much more likely failure.

"My view is that one of the key responsibilities of any entrepreneur is to create a sustainable business in a frugal manner," says Vaitheeswaran. "The fact of the matter is Flipkart is a very large loss-making company and profitability is still many years away. All of its valuations reflect future potential and promise."

However, other industry participants do not believe that a loss-making business should automatically be cause for concern. Anand Prasanna, a managing partner at Iron Pillar Capital, compares the customer acquisition process for an e-commerce company to the construction of a power plant: both represent considerable sunk costs in terms of time and capital commitment, but they also promise reliable, long-term returns that can make up for the initial investment.

"If it's a business that has great payback periods, great customer acquisition costs, and great customer retention, I would actually be very happy about a company continuing to burn capital," says Prasanna. "They're going from strength to strength and acquiring more and more of their market. Low profitability doesn't matter, because at any point if they stop burning, they can turn to profitability very fast."

In addition, Prasanna says fears that the exit will prompt entrepreneurs to pursue large valuations while operating a loss, rather than aiming for profitability, are unrealistic. In India, as in any other market, entrepreneurs are not monolithic: some will want to build lasting companies that can stand the test of time and eventually go public, while others will choose to grow their businesses quickly and look for a trade sale exit.

Both approaches have their place in a healthy entrepreneurial ecosystem. A single deal, no matter how large, will not convince any founders to change their plans from one to the other. Moreover, entrepreneurs can look to other industries, such as IT outsourcing and gaming, for examples of successful IPOs in India.

A more widely acknowledged worry in India's VC community has to do with the contrast between the Flipkart exit and those of its peers in other markets. In China, for example, the runaway market leaders in the e-commerce space, Alibaba and JD.com, went public in 2014. Younger unicorns such as Didi Chuxing in ride-hailing, Meituan-Dianping in online-to-offline services, and Alibaba-owned internet finance business Ant Financial plan to follow suit within two years.

By comparison, the only Indian unicorn to produce an exit so far is Flipkart, and this was through a trade sale rather than an IPO. Meanwhile, ride-hailing app Ola is also said to be exploring a merger with US counterpart Uber. The fear among investors is that while entrepreneurs may wish to take their companies public in the future, market conditions will force them toward strategic exits instead.

Here the focus returns to profit, and the recognition that the cash burn required to build a customer base in an emerging industry is not always aligned with the interests of public market investors.

"The appetite of the mainstream market for investing in e-commerce companies is still not that deep," says Rachana Kothari Doshi, an associate director at consulting firm RBSA Advisors. "Ordinary consumers might buy items online every day, but for investing it's a cash flow story. All these e-commerce companies need to find a way of turning profitable, which is what the retail investor wants from an IPO."

Members of the VC community agree that a wider range of exit options is needed, though most hope that as the e-commerce industry continues to grow the need for cash burn will ease and mainstream investors will become more comfortable with the idea of holding shares in these companies. Indeed, Walmart has indicated that it will support an IPO by Flipkart that would leave the company a majority-owned subsidiary.

Meanwhile, investors are turning to a new challenge: finding the next high-growth industry where they can build on the thesis established with the Flipkart exit. "Many billions of dollars went toward building Flipkart into what it is today," says PwC's Krishan. "I struggle to see many other such big, investable segments for VC investors at this point in time."

Sidebar: The competitive edge

Walmart's $16 billion purchase of Flipkart represents an inflection point for India's e-commerce industry, with the market now being led by three overseas players: Walmart, Amazon, and Alibaba Group, which owns a 46% of Paytm Mall. Many industry observers see the deal as a long-awaited leveling factor, giving Flipkart the capital and strategic support it needs to stand up against the US and Chinese giants.

This is an especially important consideration given the cash burn characteristic of India's e-commerce industry. Flipkart has yet to earn a profit since its founding in 2007 and has been wholly supported by cash infusions from VC investors. Walmart's deep pockets will allow the company to remain competitive. This is a relief to observers who had feared that the collapse of a proposed merger with Snapdeal last year would leave the local players weakened during a time of consolidation.

"In the Indian telecom or FMCG [fast-moving consumer goods] sectors there are a few large players who are dominating the scene," says Rachana Kothari Doshi, an associate director with consulting firm RBSA Advisors. "In telecom, for example, there is Vodafone and Airtel, and other players have largely either fallen by the wayside or been acquired. E-commerce is developing in the same direction."

Walmart was attracted by Flipkart's success building a nationwide distribution network. The company had 54 million active customers and gross merchandise value of $7.5 billion for the 2018 financial year, and the deal gives the US retailer direct access to this distribution chain in addition to its Best Price stores. In its announcement of the Flipkart deal, Walmart said it expects e-commerce revenue to grow at four times the rate of total retail revenue in India over the next five years. E-commerce penetration is projected to triple over the same period.

However, some observers downplay the long-term impact of the acquisition. E-commerce entrepreneur and author Kothandaram Vaitheeswaran believes that Walmart overpaid for Flipkart, adding that the company is too new to India and unfamiliar with the needs of its e-commerce market to provide much strategic help in the short term. The danger is that Amazon and Alibaba will consolidate their lead while Walmart and Flipkart figure out how best to work together.

"If you look at Walmart's track record so far, it's been quite modest," says Vaitheeswaran. "They've been fighting Amazon in America for 10 years, and Amazon has stayed ahead. They've battled Alibaba in China and Alibaba is still ahead. To now expect to go into India and fight them both at the same time, having come in late, is something I'm not sure is likely to succeed."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.