Coronavirus & leverage: Room to maneuver?

Economic disruption caused by the coronavirus outbreak is likely to leave many private equity portfolio companies in breach of their leverage covenants. Borrowers and lenders are looking for a fix

Of the more than 400,000 foreign students enrolled in higher education courses in Australia, China accounts for above one-third. It remains to be seen how quickly they return to class.

International education is one of countless areas experiencing uncertainty and chaos as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. Australia, like many other nations, closed its borders to all apart from citizens and permanent residents last week. But the ban on international arrivals who have traveled from or through mainland China was introduced in February. Depending on how long the lockdown continues, educational institutions could be deprived of a key source of income.

Having contributed A$21 billion ($12.5 billion) to Australia's GDP in 2018, and with nearly 25% of students from overseas, international higher education is big business. Disruption to this lucrative dynamic is already affecting private equity investors interested in the space. Laureate Education has yet to announce who will buy its Australian and New Zealand operation, despite PE and strategic bidders aggressively chasing the asset. With debt and equity markets suffering convulsions, the buyers – and their financiers – might be waiting for the confusion to clear.

Questions are also being asked of another business, Navitas, which puts students into academic programs as a stepping stone to university enrolment. BGH Capital acquired Navitas for A$2.1 billion last year, supported by A$1.1 billion in debt. Is this structure robust enough to bear a drop-off in revenue without sliding into default? The message from a source close to the deal is unequivocal: "There is no – as in zero – chance Navitas breaches its only covenant for many, many years."

Two weeks ago, leveraged finance professionals were still working on new deals for PE firms enjoying a prolonged period of ample liquidity. Now, sponsors and lenders alike are scouring the operational metrics and financial structures of existing portfolio companies for signs of weakness.

The speed of the decline has caught everyone off guard. In the past fortnight, the Credit Suisse leveraged loan index marked its three worst days on record in just a four-day window due to a large-scale sell-off across all industries and ratings. Yields in the high-yield markets increased by 676 basis points over the course of four weeks, a steeper sell-off in a shorter period than the euro zone and Brexit crises of 2011 and 2016. Even in the global financial crisis, it took 78 weeks for yields to peak.

"The market as a whole is taking a step back – it's been fascinating because we're in several live situations," says Peter Graf, head of leveraged finance in Credit Suisse's Asia Pacific financing group. "If you look back at the global financial crisis, it played out over 6-9 months and then it took down the global economy after 12-18 months. Today, the speed of the sell-off has been so much faster and we need more time to assess the full impact."

Double wave

From a leveraged finance perspective, this impact will come in two waves: the first immediate as companies secure short-term liquidity; the second over the next three to nine months as the covenants attached to term loans that underpin LBOs undergo quarterly financial performance tests. The covenants in question are designed to capture whether a business can make interest payments on its debt and whether it can sustain operations under its current debt load and budgetary commitments.

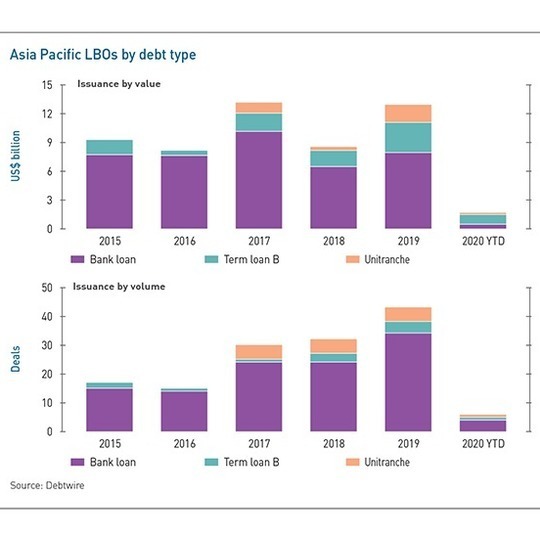

Confidence in the Navitas structure likely stems from a high bar in terms of what the company must do to breach its covenant or wide scope in what it can do to make amends. It is one of few unitranche structures in the market that offer such flexibility. Covenant-lite deals that aren't subject to these quarterly maintenance tests are equally rare. Four-fifths of the more than $50 billion raised by financial sponsors for leveraged buyouts in Asia Pacific since 2015 come from the traditional bank market, according to Debtwire. Regular principal payments and multiple covenants come as standard.

"It's all about the roll forward," says Edward Tong, head of private debt for Asia at Partners Group. "As you move into June and then September, how quickly is a business able to recover? How much of a liquidity buffer do you have? How much headroom is there in the documents? And how much cash are you sitting on? We have seen incidences where a certain amount of conservatism has been applied early in the life of a transaction. There's cash that brings the net leverage down. If you do have a shock, that additional cash acts as a buffer against a short-term deterioration. But is it sustainable?"

Covenants are calculated on a 12-month trailing basis, which means one or two quarters of pain could be counterbalanced by earlier robust performance. Moreover, there is normally a 30-60-day lag before companies must share their numbers with lenders. But financial sponsors are not hiding their heads in the sand: they are already reaching out to lenders, warning of impending difficulties, and looking for short-term cash and longer-term alterations to debt facilities.

"What's the saying? Ostriches rarely perform well in crises," says Alexander McMyn, a partner at White & Case in Singapore. "Sophisticated borrowers, whether they are financial sponsors or corporates, will be on the phone early with their banks. Banks get a lot more worried by silence than by getting calls. It's the lack of information and ignorance that trouble them most."

Short-term needs

Regarding interim liquidity, financial sponsors need to ascertain whether portfolio companies have enough cash to sustain themselves for the next three to six months. They are stripping out costs: putting capital expenditure plans on hold, eliminating non-essential expenses, asking landlords for breathing space on rent, and exploring temporary or permanent job cuts. They are also drawing on any existing facilities they have with banks, unless these facilities have covenants that restrict such behavior.

From multinationals to mid-size corporates, revolving credit facilities (RCFs) – obtained at the same time as term loans but intended to cover fluctuations in day-to-day operational cash flow – are being drawn to the max. Previously, a company might have used $100 million out of a $1 billion facility. Now it is taking the full $1 billion, regardless of immediate need.

"People cast their minds back to 2008-2009 and they worry about counterparty risk, so they draw first and prepare for the worst," says Tong of Partners Group. "If the worst doesn't happen, they've drawn more than they should have done but it's easier to pay it back after the fact than take some credit risk on a lender's ability to fund the drawdown request."

There is general acknowledgment that the current situation is not a repetition of the global financial crisis, where the banking system was in such a state that lenders stopped funding credit lines. Rather, facilities are drawn for a combination of psychological and tactical reasons. As one fund manager puts it: "There's a spiral effect. No one wants to be the last one in the queue holding up their hand when the tap turns off."

In some cases, banks are encouraging key financial sponsor clients to take advantage of the RCF, warning that it's much easier to help a company with a covenant breach – assuming it is viewed as a temporary aberration driven by exogenous factors – than one that has run out of money. In other cases, financial sponsors are securing cash now for fear that a downturn in business could trigger a material adverse change (MAC) draw stop, enabling banks to switch off credit lines.

"It's tough to exclude the MAC clause in its entirety from a deal, but sponsors use their negotiating powers – they might have relationships with a bank across multiple portfolio companies – to drive an optimized interpretation of that clause, such that it is very narrow," the manager adds. "What keeps me awake at night isn't a covenant breach but not having enough cash to weather the storm. If I was worried that revenue might dry up in a couple of months, I would draw the revolver in full today, so there's no ambiguity for the banks to try and assert the MAC has been breached."

Some cov-lite structures come with a springing covenant that introduces maintenance tests once the RCF is drawn down by 40%, with failure placing the facility into default. However, the financial sponsor usually has the option of implementing an equity cure, whereby it injects capital to increase EBITDA, reduce debt, or pay off part of the RCF.

"There are various ways to carry through," says Russell Sinclair, a member of PwC's Australia debt and capital advisory practice. "What mattered most when you first raised the debt? If it was flexibility, then you'll have made room on covenants."

Waive or amend?

Even though relatively few financial sponsors in Asia have been able to tap the US bond markets and secure cov-lite financing, covenants have become looser in recent years as a result of increasing competition among lenders. Nowhere is this more apparent than Australia, which remains the only jurisdiction in the region where private debt funds have mounted a meaningful challenge to banks.

US term loan B (TLB) remains, for many, the optimal arrangement. Pricing is tight, gradual amortization is replaced by a bullet repayment on maturity after seven years, and there is flexibility on dividend payments and capital expenditure. Moreover, covenants are only tested on an incurrence basis, such as when the borrower issues new debt or engages in M&A.

Unitranche was introduced in 2017 as a compromise solution. Combining the senior and mezzanine facilities into a single piece, it offered Australian dollar-denominated debt with zero amortization, a single maintenance covenant for leverage, and lower pricing than the mezzanine lenders. HPS Partners and Partners Group dominated the initial deals, but they have been joined by the likes of KKR, Bain Capital, ICG, Barings and various local providers. Tweaks to the Australian TLB – described as unitranche in all but name, with some differences in the fine detail of the documentation – are said to have followed.

To date, Unitranche has been used to support 16 leveraged buyouts in Asia, with aggregate debt of $3.6 billion, according to Debtwire. Most of those have been in Australia. Left with the role of super-senior RCF provider, local banks responded by offering improved terms to sponsors that didn't need the 6x debt-to-EBITDA leverage multiples typical of TLB and unitranche deals. They pushed up leverage, pushed out amortization, and reduced the number of covenants from four to two.

Lyndon Hsu, an experienced leverage finance executive in Asia, warns of the prospects for some of these deals, especially the class of 2019. "Some were done at up to 6.5x, and in one case apparently 7x," he says. "Australian credits could experience 12-24 months of deviations of several standard deviations of downside risk. If hospitality, transportation and services remain subdued for a long period of time, those businesses could collapse under the weight of their debts. A company with a high degree of operational leverage – such as a restaurant chain that rents its premises – could hit stress even with 4-4.25x leverage."

Covenants give lenders recourse, the ability to bring borrowers to the table for discussions on what can be done to revive a business. The greater the number of covenants, the better the chance of capturing any slip. However, EBITDA is the common denominator across all major covenants. A blowout in revenue of the magnitude some companies are facing due to COVID-19 would hit EBITDA and trigger a breach regardless of whether there is one covenant or four.

There might be some devil in the detail. A financial sponsor pushing for maximum flexibility may have negotiated a definition of EBITDA that allows for adjustments driven by one-off events. Similarly, on completion of a deal they could point to synergies, such as from a bolt-on acquisition, that are expected to deliver cost savings and have them wound into EBITDA ahead of realization. This manipulation of covenant calculations could provide more headroom and prevent a breach.

"There is an artificiality in that people say there are still covenants in Asia – they are so full of exceptions," says Charles McConnell, another partner at White & Case. "Will people breach? It's more likely in Asia than Europe, but there is still so much flexibility and long-worded provision with vague language that they will make a good go at saying they won't breach."

When financial sponsors are forced to engage with lenders, there are typically two priorities. First – and not for those with TLB or unitranche structures – they want amortization relief. This could involve bringing repayments to an immediate standstill as the portfolio company seeks stabilization and the pushing out the remaining amortization schedule as far as possible, perhaps even converting the term loan facility into a bullet structure.

Second, they want more flexibility on covenants, either in the form of a waiver or a renegotiation of covenant headroom. Most industry participants see the latter as preferable. A full renegotiation is contingent on the financial sponsor providing revised financial projections for the portfolio company, something many are unable to do given the current volatility. Obtaining a waiver – or a temporary suspension of covenants – rests on convincing lenders that the company is taking measures to mitigate the COVID-19 impact and will survive. But it really depends on how bad things are.

"As a deal progresses, covenants ratchet down and principal repayments ratchet up. You get a double whammy and sponsors must deal with those dynamics," Hsu explains. "Say your debt-to-EBITDA was 3x and you had 4x leverage coverage headroom. Then your EBITDA collapses and 3x becomes 3.5x at the end of June and will be 4.3x by December. You want to ask for a new covenant to be set at 4.75x. That type of conversation will happen in greater volumes as the year progresses."

Relationships matter

A key consideration is the number of counterparties involved in this dialogue. Bank financing packages might include 30 or more lenders, many of them small-ticket names with allocations of $5-10 million. Drumming up majority support is a challenge. By contrast, the unitranche provider universe is relatively concentrated. A financial sponsor might only need to negotiate with one credit fund – but if that fund is unwilling or unable to offer any leeway, the talks would be short-lived.

Asked which situation he would prefer, one manager opts for unitranche, in the expectation that credit funds would be generally supportive. However, he adds a caveat: if the portfolio company also has a pressing liquidity issue, it is better to have lots of existing lenders whose core business is lending money. This underlines the importance of relationships – whether negotiating changes to existing facilities or securing new ones – and the fact that behavior will differ by lender type.

"Banks tend to be relationship-driven and will focus on key sponsor clients during times of volatility. This means any movement in terms is usually less extreme than the broader capital markets. Institutional lenders tend to be relative value players and will look for the best returns across the primary markets, the secondary markets and in different geographies, currencies or product groups. As a result, the liquidity from institutional lenders is likely to flow to those markets that offer the most attractive opportunities and can impact yield requirements for the primary market," says Andrew Ashman, head of the Asia Pacific loan syndicate at Barclays.

Dialogue between borrowers and lenders will evolve in real time, driven by the immediacy of potential covenant breaches and how quickly COVID-19 can be brought under control. As things stand, it might be safe to assume that lenders will be amenable, but this doesn't equate to uniform treatment. The status of the sponsor – and the lender's relationship with the sponsor – will influence decisions alongside analysis of individual companies and the industries in which they operate.

The most important question is whether a business would come under stress regardless of COVID-19. Tigerlily, an Australian clothing retailer owned by Crescent Capital Partners, entered voluntary administration this week, with reduced shopping center footfall as a result of social distancing cited as a contributing factor. But the company, which has 30 outlets nationwide, was already struggling.

Brick-and-mortar retail would feature prominently on the list of industries unlikely to find favor with lenders, adding to the spate of distressed opportunities in the space. How far the contagion spreads rests on whether economies globally slip into recession – and current pricing in the public markets suggests investors attach a high likelihood to this outcome.

Even where lenders agree to a reset on existing facilities rather than just dumping the debt, there will be openings for special situations investors. For example, if senior or subordinated lenders are unwilling to increase their exposure, other parties can step in with a convertible preference note or a more equity-like instrument. David Couper, a partner with law firm Allens, believes it will be a target-rich environment for private lenders able to provide financing solutions tailored to specific requirements regarding quantum of capital, tenor, and flexibility.

These scenarios are waiting to play out once the climate of uncertainty dissipates. For now, Russell of PwC is just happy that people are talking about it. "There are lots of calls asking for advice on approaching different issues," he observes. "The worst thing that could have happened is people throwing up their hands and saying it's all too hard. At the moment, there are some sensible heads saying we have to try and find a way through."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.