Global credit: Speed or scale?

The winners from a widely anticipated shakeout in global credit markets will be defined by different qualities. Direct lenders expect size to be a decisive factor, while distress players prioritize nimbleness

Bain Capital's entry into the Australian credit market was facilitated by three acquisitions over the course of three years. In 2013, it paid more than $300 million for a portfolio of corporate loans from Lloyds Banking Group. This was followed by the acquisition of J.P. Morgan's Global Special Opportunities Group, which had meaningful Australian exposure. Finally, Bain picked up GE Capital's A$2 billion ($1.4 billion) commercial lending and leasing business in Australia and New Zealand.

The firm now claims to be one of the largest private lenders in the country. While buying existing portfolios of assets represented a jumpstart, it was accompanied by a commitment to the Australian market manifested in the recruitment of a local team and the opening of an office in Melbourne.

"The GE commercial finance business came with about 100 relationships with individual businesses where we became the current lender. When it comes to doing due diligence, getting a head start and directly originating loans, an existing relationship and existing diligence on a company can be valuable," Michael Boyle a managing director with Bain Capital Credit, told the AVCJ Japan Forum. "But buying a portfolio to enter a geography is helpful, not mission-critical. Having a local team is mission-critical."

Scale of resources is expected to be a key differentiator when the global direct lending space – characterized in recent years by abundant capital, elevated prices, and squeezed returns – goes through its inevitable shakeout. Large incumbents with local teams capable of originating transactions and driving outcomes will prevail. New entrants that have chased deals at the expense of discipline on terms and tightness on covenants, usually by participating in club deals or syndications, will flounder.

In other segments of the credit market, however, size does not conquer all. Ares Management is raising a distress fund precisely because it believes a swathe of restructuring opportunities will arise from situations in which second-tier direct lenders have been too aggressive on terms. But the firm is wary of raising too much. In 2018, direct lending strategies accounted for 80% of the $31.6 billion committed to Ares-managed credit funds. The firm's latest global distress vehicle reached an initial close of $1 billion in June and is expected to reach up to $2 billion in the next 12 months.

"There are certain sectors where size is a deterrent to performance and certain sectors where size drives performance. We believe that in direct lending, size drives performance. In distress, I think it's the opposite. Being more opportunistic, being nimbler is important. If you have a fund that is too big, you become an index for the distressed market," says Greg Margolies, a partner with Ares.

Being local

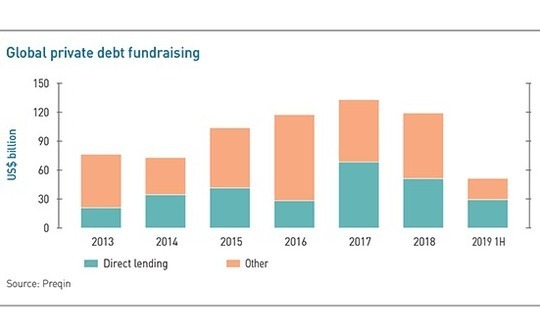

Global private credit fundraising reached $118.4 billion in 2018, according to Preqin, down from $132.2 billion the previous year, but still the second-largest annual total on record. Direct lending has been the major growth story of recent times, rising from $20.8 billion in 2013 to $67.9 billion and $50.8 billion in the last two years.

Large managers tend to attract a disproportionate amount of capital. In the first quarter of 2019, for example, 13 final closes by direct lending funds were responsible for $16.9 billion out of $23.9 billion raised across all credit strategies. The top four accounted for $14 billion. Nevertheless, there is a long tail. Commitments have more than doubled in US dollar terms since 2013, but the average fund size has increased by 50% to $605 million last year due to strong growth in new arrivals. Margolies estimates that 75% of all capital raised for direct lending in 2018 went to vehicles of $250 million and below.

"To find the best value in direct lending around Europe, you have to be local. You just can't do it from one base, typically London. To do deals in France, you need a French team in a French office, and that echoes across the continent," says James Greenwood, CEO of Permira Debt Managers, which focuses on direct lending in Europe. "As I look at the European landscape, there are maybe 30 lenders I can name that are active in the market and there is a clear separation between the larger players that have scale – maybe five or six – and the rest, who are trying to get specific by sector or geography."

Several groups have expanded into Europe from North America and failed to achieve scale because they used London as a hub for the region rather than build out a local office network. Ares is among those that succeeded. It is present in seven cities in Europe, as well as eight in the US, with more than 150 investment professionals dedicated to originating middle-market loans in the two regions. This growth involved a significant upfront cost: Ares wasn't profitable in Europe until the beginning of its third fund.

"We were investing from a management company perspective for many years before we saw any return on that. Now we underwrite close to 50% of the deals in Europe's middle market," says Margolies. "It was a long road for us before we were profitable, but we had to build the infrastructure before the AUM [assets under management] came because if you are not local, if you don't have the ability to originate and diligence, it won't end well."

Dealing in distress

Not everyone is completely sold on the notion of a handful of large players emerging from the wreckage of an overpopulated global direct lending market. While admitting that size can be helpful, Dennis McCrary, a partner at Pantheon, which primarily participates in private credit as an LP in secondary funds, also sees scope for customization and specialization. There are already healthcare-focused lenders in the US and more sector specialists are set to emerge as credit follows the footsteps of PE.

"There are opportunities to be a smaller and successful player if you have a specialty, a competitive advantage. This might be sector expertise or knowing an individual country well," McCrary explains. "In the distress space, 80-90% of money raised recently has gone to the 10 biggest funds. You could argue size does matter there – you need tentacles all over the place."

Those tentacles facilitate cross-fertilization between direct lending and distress strategies. For example, Bain Capital acquired a portfolio of Irish non-performing loans (NPLs) in the wake of the global financial crisis. Once it worked through those and the economy rebounded, the firm was able to generate lending opportunities from the same set of corporate relationships. A similar knock-on effect is expected from NPL deals in Portugal, Spain and Italy.

The bigger challenge is predicting where opportunities might arise in the other direction, from direct lending to distress. Several investors observe that assessing weakness below the industry level is complicated by opacity. If a company's outstanding debts are packaged into a collateralized loan obligation (CLO), investors in that product are leveraged. If the company is subject to a buyout, the transaction is likely to be leveraged and the PE firm might have additional leverage at the fund level. On top of that, a secondary investor could use debt to support the purchase of an interest in the fund.

A sudden change in market conditions and the behavior of individual industry participants will come into focus but peeling back the layers of apparently strong credits is a time-consuming process. "It's hard to time when the next distress cycle will hit," says Bain's Boyle. "Our point of view is you want to allocate capital to distress earlier rather than later. If you wait for the cracks to appear in the corporate distress cycle, it is likely to be too late to get that capital deployed."

As a result, there is an emphasis on mobility – leveraging global networks to move quickly when opportunities emerge but with flexible pools of capital, rather than funds that are too cumbersome to deploy efficiently. These opportunities are all about finding an edge. It might mean targeting less liquid markets and structural complexity or identifying capital vacuums in areas that tend to get overlooked.

CarVal Investors, which manages about $10 billion across distressed credit globally, has found angles around residential mortgages and solar in the US. Banks want to sell the former because the regulatory capital requirements are twice as high as for new loans. As for the latter, the capital markets haven't kept pace with industry growth, creating opportunities to buy small-scale commercial solar projects and fund the installation of solar panels in homes.

"In both cases, we are creating cash flow streams in the low double digits or high single digits. They are unlevered and of high quality," says Chris Hedberg, CFO at CarVal. "Those returns are not caused by distress, rather there is a dislocation or inefficiency of capital. In this environment, those are the things we are focusing on and then relying on a broad global team to do the more traditional distressed investing when the cycle does turn."

Flexibility first

Even when this happens, some investors advocate sticking to an opportunistic approach. Greenwood of Permira notes that classic loan-to-own players that buy up corporate debt and seek to assume control in the event of a covenant breach struggled to gain traction in Europe during the global financial crisis due to complex insolvency regimes and protracted processes. While he expects deal flow to emanate from NPL sales and stress in direct lending, niche and nimble strategies might be the best performers.

This view is shared by some in the LP community who prioritize flexibility in challenging times. One investor cites the high-yield crisis in late 2015 as an example. Falling energy prices, a weak macro environment and fears about deteriorating credit quality sent bond prices into freefall and redemptions soaring. Third Avenue Management was forced to gate one of its high-yield funds because liquidity had dried up and the only way it could pay back investors was to sell assets at fire-sale prices.

The LP favors master custody agreements – whereby portfolio managers, having been allocated capital for a set period under a fee structure that doesn't distinguish between investment structures, bring opportunities to the LP as they arise – because they allow a higher degree of autonomy. It contacted GPs and told them the checkbook was open and that it wanted to buy distressed assets. More than $80 million was deployed in the space of a week before the market stabilized.

While the amount of capital being pushed into the credit space by institutional investors seeking yield in a pervasively low-interest-rate environment is disconcerting, the LP expects opportunities to emerge – for those who can move quickly. "If you are not a model investor or holder of a certain kind of investment, you tend to be skittish in behavior and throw the baby out with the bathwater when markets go down," the investor tells AVCJ. "We can step in as a liquidity provider."

SIDEBAR: Asia credit - Work in progress

Asia special situations fundraising is seldom indicative because local managers are relatively few and most international players operate through global funds. AVCJ Research's numbers for the first half of 2019 stand out for a different reason: the bulk of the approximately $2 billion raised was for India.

Foreign investors are piling into India's distressed asset space, looking to tap restructuring opportunities expected to arise from the $200 billion in non-performing assets (NPAs) sitting on the balance sheets of the country's banks. They strike partnerships with local operators but there are no specific deployment targets – capital is allocated from other pools when required.

Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) therefore went against the grain when it wrote a check of $500 million for a special situations fund launched in conjunction with Kotak Private Equity. The headline fundraising number received a further boost when Edelweiss Alternative Asset Advisors closed its latest stressed assets fund at INR92 billion ($1.3 billion), up from $77 million for the previous vintage.

Credit advances across the entire Indian system have grown from $200 billion in 2008 to around $1.4 trillion today, according to Haseeb Malik, a Singapore-based partner with Värde Partners. As the market has developed, creditor rights have formed and been challenged.

"It is a learning process in terms of how banks lend and how intercreditor issues work," Malik says. "Since the insolvency code started to get implemented in 2017, creditor rights have got more attention and the code brings predictability. That transparency, and the protection of creditor rights, is important in the evolution of the Indian credit market."

Värde, which has $14 billion under management across corporate and traded credit, real estate, mortgages, financial services, real assets and infrastructure, entered the India market last year through a stressed and distressed assets JV with Aditya Birla Capital, the financial services arm of the Aditya Birla Group. Another JV has been established in Indonesia.

These are integral to the firm's approach to Asia, which comprises multiple markets that differ in language, culture, and regulation. Those issues aside, a local presence is essential to building up a meaningful deal sourcing network. "It's part of our right to play," Malik adds. "We are going to be thoughtful on picking the markets we play in – wherever we go, we need to have not only knowledge, but also a repeatable and scalable business."

Once on the ground, flexibility is the key to making investments. Bottom-up analysis is used to identify the best way to capitalize on an opportunity with a company. It may involve buying up non-performing loans (NPLs) and driving a restructuring or primary lending intended to solve liquidity needs. When the objective is filling a liquidity gap, it's usually due to banks not lending to a certain sector, changes in regulation, or capital demand-supply mismatches.

Malik sees parallels between the early evolution of credit markets in Asia and Europe in the 1990s and early 2000s. Filling gaps is a common theme. "Banks want to lend to high-quality credit and also the flow of money from institutional investors into private credit is relatively small," he says. "Even a developed market like Australia has very few high-yield issuers. If you're not in the top 30-40 companies, banks have a higher bar to lend to you, and as a company it's also hard to get access to public credit markets."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.