Asia private debt: Inflection point?

With other pools of capital running dry for many companies, private debt has become a more appealing proposition. Institutional funds have a chance to impose themselves on a bank-driven market

ICG is busier than ever before. With corporates across Asia facing liquidity crunches – or fearing they will before long – inbound inquiries have risen fourfold in the past couple of months. "As of the second week of March, the world changed from too much capital chasing too few deals to the complete opposite," says Wooseok Jun, ICG's regional head of equity and mezzanine.

"We're going to see more opportunities. Performance in the second and third quarters will be worse than the first, and once that happens, leverage will increase and balance sheets will deteriorate. This started out as a cash flow issue – survive it and everything would be fine. But now people expect a severe economic downturn, it's just a matter of how long it is going to last."

Most private debt providers in Asia have seen a surge in demand. Coronavirus-driven economic disruption has starved companies of revenue, challenged business models, and prompted concerns about the ability to service existing debts. There is a need for capital, but sources have narrowed. Debt capital markets are only accessible for large, blue-chip borrowers; banks have become less forthcoming; and equity financing – if available – comes at knockdown valuations and with strict conditions. Once deemed too expensive, private debt financing is an attractive proposition.

Rising inbound inquiries doesn't necessarily translate into increased executed deal flow. Much rests on which segments of the market an investor targets, what projected return is required to make them comfortable committing capital to situations where cash flows might be far from certain, and how close they can get to underlying assets. The most common response to invitations is still no.

"We are seeing more, but we're also rejecting more, because a lot of them just don't stack up," says Neil Harvey, executive chairman at ADM Capital. "It is often company-specific – we don't think they have the cash flow required or their leverage is too high – and then some sectors have been hit heavily. The other problem is access. The Chinese economy is picking up for example, but we can't access those opportunities and conduct our normal due diligence due to travel restrictions."

Hope springs

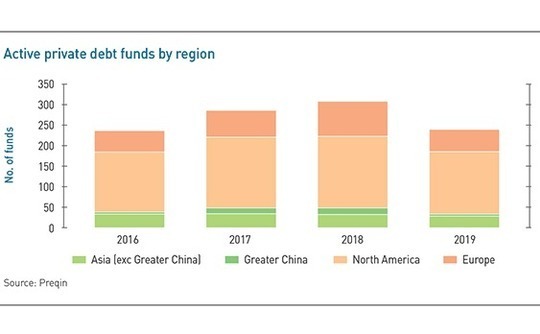

Beneath this initial circumspection, however, runs a firm belief in Asia's long-term potential. There are various reasons why debt penetration in the region lags North America and Europe: unreliable creditor rights, difficulties working in multiple currencies, complicated structures and drawn-out processes, and uncertainty as to whether there is enough deal flow to justify building a local presence. COVID-19 may help accelerate Asia's evolution from a debt market dominated by banks to one in which institutional funds have a meaningful share.

There is certainly more interest from would-be participants. Fundraising prospects may improve for the various mid-market shops that have emerged in recent years – primarily targeting a perceived withdrawal of banks from mid-market lending – while Taiwan's CDIB Capital announced the formation of an Asia structured credit group as recently as last week. Australia-based fund-of-funds Roc Partners is also considering private debt strategies, though discussions are preliminary.

"If we have a slower recovery than anticipated, we think that means a lot of this accumulated liability will come home to roost probably later in the year or in the first quarter next year," says Michael Lukin, a managing partner with the firm. "It could be bridge-style financing – a scenario where the banks are tapped out, the GP is maybe tapped out from a portfolio construction perspective, and you target the companies that will to do well in the post-COVID environment but potentially need some capital to restart, and regear, and provide a working capital solution."

"We've seen public opportunities and separately private opportunities over the last two months," observes Robert Petty, co-CEO of Clearwater Capital Partners. "The public markets move viciously and fast. While no one was unscathed, we were able to move quickly and participate in some of the compelling discounted valuations in the public market space that have somewhat normalized over the most recent weeks."

The most immediate private opportunities involved rescue financing for companies in sectors like travel and hospitality that were hardest hit by COVID-19. Not all private debt investors play in the distress space, but it is one of three prongs to Bain Capital Credit's (BCC) special situations strategy, alongside structured primary capital and purchasing portfolios of non-performing loans (NPLs). The firm has completed one rescue finance deal in recent weeks and just signed another.

Non-distress situations take longer to process because the companies have time to adjust to the new normal. They have sufficient near-term liquidity, but revenue has deteriorated to the extent that covenants on existing debt facilities will be breached or they will struggle to refinance on previous terms because leverage levels are higher.

Private equity-owned companies are among the more proactive when it comes to addressing problems. A significant portion of ICG's activity in this area involves dealing with financial sponsors that fear a covenant breach in the next 12 months and don't want to negotiate with banks over a waiver because they know there will be an additional fee and a repricing of the existing debt. ICG extends financing that allows the sponsor to pay down some of the debt and avoid a breach – provided that the financing can ultimately be taken out by a cheaper form of debt.

"There are a lot of situations where companies are fundamentally strong but have liquidity issues. The popular belief was that typical offshore mezzanine was too expensive. Now there's no such thing as easy money, price has become secondary to certainty," says ICG's Jun. If the cost of mezzanine in Asia's more developed markets is 8-10%, he estimates that demand would still be strong even with 300 basis points on top of that range.

Strategic withdrawal

The longer-term opportunity – and arguably the most profound – is supporting companies that need capital for growth. The lingering question is who will provide it, especially in a recessionary environment. While countries across Asia have rolled out policies intended to keep banks lending to local companies, this will hold only as long as government money is being put to work. After that, industry participants expect a flight to quality. The reality is very different for large corporates versus small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), but there are some common themes.

BCC is already getting traction with corporates that previously had little interest in private debt solutions. "They would not have considered alternative capital because they had access to cheaper bond, bank or public equity solutions. Now they are engaging with us quite seriously on multiple hundreds of million-dollar solutions, and in one case touching $1 billion" says Barnaby Lyons, a managing director and head of Asia at BCC. "They need capital to resolve balance sheet stress or because they see acquisition opportunities for themselves in this environment."

FC Capital is about as far removed from BCC as it is possible to get, lending sums of up to A$20 million ($12.8 million) to SMEs in Australia that aren't covered by local banks. However, COVID-19 has broadened the opportunity set. "I am seeing larger businesses that would typically not come across my desk because they get cheaper funding elsewhere. They can't get that funding, so they are looking wider to deal with their issues," says Alan Butterfield, head of FC's credit opportunities fund.

Last week, HSBC allocated $3 billion for loan provisions in anticipation of potential bankruptcies and defaults due to the pandemic. It warned that provisions could reach as high as $11 billion by year-end. Major US and European banks collectively expect to book $50 billion of charges on stressed or soured loans in the first quarter, the most since the global financial crisis. The consensus view is that they will become less willing to look beyond large, established relationships in corporate lending.

Asian banks are tipped to be similarly inclined. "If you were a Taiwanese lender and you were desperate to finance overseas, you were pushed into racy structures that maybe you shouldn't be doing. High up in the credit cycle, the yield differential between plain vanilla investment grade and highly structured lending recedes – everyone thinks they can do everything," says Erwan Stervinou, a partner at mid-market Asian credit investor Sammasan Capital. "However, at the first sign of problems, when one Taiwanese lender catches a cold, all the others run back home."

In this sense, COVID-19 might accelerate two trends: one cyclical, where banks retreat from complex, highly structured products; and the other structural, where they cut back on lending to SMEs. The latter has become increasingly apparent in the Asian market – where it is estimated that banks account for 95% of senior debt issuance outside of China and India, which have traditionally relied more on non-bank, local currency lenders – over the past four or five years.

Value proposition

While private debt could fill a gap in the capital structure vacated by banks, Sabita Prakash, who chairs ADM's investment committee, describes her firm as a collaborator rather than a competitor to traditional lenders. ADM seeks to address the credit void whilst meeting a number of other borrower requirements. "They might need a fast-moving lender with capabilities across markets" she says. "Or it could be they want something underwritten in a flexible structure that combines collateral and cost in a way that meets their needs and abilities."

Depending on the situation, private debt investors are comfortable with subordinated or preferred equity structures and customized repayment schedules that are back-ended or incur PIK (payment-in-kind) interest. Banks don't have the appetite for these. Moreover, while banks like traditional asset-heavy collateral in markets they understand, private debt players would consider contracted revenues or royalties. They will also lend in one jurisdiction against assets held in another; banks prefer guarantees at the parent company level.

Chris Chia, a managing partner at Kendall Court Capital Partners, which focuses exclusively on growth-oriented businesses in Southeast Asia, points to a recent healthcare investment in Indonesia. Revenue was strong in the run-up to the COVID-19 outbreak but was significantly affected due to the lockdown measures. However, the company did not need additional capital because Kendall Court's investment structure was built to cater to a business downturn by allowing headroom on repayments.

Equally, private debt might serve as an attractive alternative to private equity. The former has always been preferable to the latter among founders that don't want to dilute their equity ownership. It might be especially pertinent now, given how recent declines in public market valuations are filtering through to the private markets. Why accept the equity dilution when a private debt solution – with a lower target IRR than PE – could see you through the next 24 months?

Many of these growth opportunities will take several months to materialize. This is partly because targets are holding out for as long as possible in the hope that they can engage with lenders in a more normalized environment and obtain more favorable terms. Investors are also biding their time. "When it does turn around, it will be a bonanza for people like myself," says FC's Butterfield. "Now is not the time to burn a lot of capital on deals I can't identify."

Some of the larger companies will ultimately return to their original sources of funding, but it is hoped that familiarity with private debt facilitates repeat business. One of the major challenges facing the asset class in Asia is a lack of understanding of the product. At one end of the spectrum, companies know what to expect from their banking relationships; at the other, they have a strong grasp of equity; private debt can get lost in the middle. However, if they move into this middle ground by necessity, they may appreciate what it has to offer, and stay by choice.

Educating business owners as to their options typically falls on financial advisors, not all of whom are plugged into the debt market. Zerobridge Advisors was established with a view to raising a fund and making private debt investments in Asia, but the firm is currently more active on the advisory side, establishing the needs of prospective borrowers and matching them with appropriate credit funds. According to Rahul Kotwal, the firm's founder and managing partner, the two business lines are highly interdependent.

"For me to have a scalable business on the investing side, I need a scalable origination machine otherwise it just doesn't work," he says. "It is difficult to get high-quality deal flow from third parties that allows you to invest in a timely manner. Most middle-market opportunities come through brokers and finders. They talk to a couple of lenders, and if those say no, they reach out to a friend who knows a few more lenders. It daisy-chains into 10 guys, all of whom want to get paid. They aren't adding any value and it can just kill deals."

The firm has sought to institutionalize and scale-up deal flow through partnerships. Most recently, it formed an alliance with BDA Partners, a boutique investment bank that works with corporates and financial sponsors on M&A and equity fundraising. The goal is to leverage BDA's network of investment bankers to put a wider variety of financing options in front of clients.

For deals of a certain size, much of the advisory work used to be carried out by mainstream investment banks. However, with the demise of proprietary trading desks, they are no longer participating as investors, so fewer resources are devoted to these transactions. The absence of supporting infrastructure – which means opportunities are less likely to arrive well-structured and diligence-ready – places a greater onus on the internal capabilities of private debt investors.

A busier market?

Zerobridge estimates there are 10-20 consistently active institutional players with mandates for Asia. Only about 10 can write checks of $50 million and above. While it is generally accepted that this number will swell over time – to the point that the region's private debt ecosystem could look more like the US or Europe 20 years from now – there is not necessarily agreement on the timeline.

Some industry participants argue that local infrastructure requirements remain an obstacle, regardless of how dislocations related to COVID-19 underline the potential for the asset class. Daniel Kwan, head of mezzanine capital at OCBC Bank, which focuses on Southeast Asia and China, believes that private debt will continue to grow steadily, but he doesn't see an inflection point.

"There are many factors to why but chiefly it's because there are not that many private debt funds covering Southeast Asia," he says. "It's a chicken and egg situation. I think those who come here to set up a mezzanine fund need patience to grow that portfolio; deal sizes are generally smaller and take a bit more work when it comes to structuring as well. I think that patience is somehow lacking because there haven't been many deals done. Funds are not set-up overnight just because there is a perception that there are opportunities in the market at this particular point in time."

Indeed, it remains to be seen whether more global firms will seek to add themselves to the cohort of established names that operate in different segments of the market. In the US, they have substantial operations that turn around $500 million deals within four weeks. Pursuing an Asia opportunity characterized by smaller tickets and longer processes might not appeal on a relative basis.

Lyons of Bain Capital Credit, which has over 70 deal and asset management professionals covering special situations in Asia, warns that building out a meaningful footprint is expensive and involves negotiating considerable regulatory complexity. However, he adds that it is important to be regional; a geographically imbalanced platform can be dangerous because it can make investors beholden to certain markets. Others suggest that the landscape is already thinning out as non-Asian credit providers choose the familiarity of their home territories over the complexities of Asia.

"Simply put, the competition's being roughly cut in half," says Clearwater's Petty. "Even if Asia is recovering better economically, the orientation of many of the global private debt providers seems to have pivoted back to their domestic markets."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.