Development finance: The great game

As the US overhauls its development finance institution in response to China’s growing infrastructure investment, the PE industry is preparing for a world in which politics goes hand-in-hand with capital

For policy makers in the US, nothing crystalized the fears of China's rise quite like the launch of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2015. The birth of a new multilateral development bank with nearly $100 billion in committed capital for deployment worldwide was a serious enough challenge to US global leadership – but the biggest shock was when the UK announced that it would sign on as one of the 57 founding member nations.

"There were jaws dropping around the world, but particularly in Washington it was seen as a huge betrayal that they were supporting AIIB," says a manager at one development finance institution (DFI). "And that led most of Europe to come on board as well."

Now in its fourth year, AIIB stands as a powerful reminder that China has the financial resources to counter US economic power and is gradually building the political will to use it through initiatives like One Belt One Road (OBOR). Critics of these projects paint a worst-case scenario of a "weaponized" form of development finance in which China uses the offer of needed infrastructure investments to extract diplomatic concessions from recipients.

The US has responded with a major revamp of its development finance strategy and the transformation of its principal DFI, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), into the US International Development Finance Corporation (USIDFC). The new organization will have not only a larger investment corpus but considerably expanded powers from its predecessor, including the ability to invest in equity rather than debt and greater flexibility in partnering with foreign entities.

These changes stand to bring significant benefits for Asian private equity firms, which have long seen OPIC as an attractive potential partner but struggled to satisfy all of its requirements and accommodate its unique deal structuring. The agency has fueled these hopes in communications with Asian GPs.

"They're already starting to tell managers that, possibly even by the end of this year, they'll be able to write fairly substantial equity checks," says the founder of an Asian GP that met OPIC's funds team earlier this year. "Say what you will about OPIC, but they understand that having a different form of capital does make it harder for other DFIs to work with them. I think they're quite looking forward to being able to make large equity commitments like other LPs."

Trump's legacy?

The irony of the biggest expansion of US development finance in decades being authorized by a president famously suspicious of US engagement overseas is lost on nobody. On the campaign trail, complaints about ungrateful recipients of foreign aid were a constant refrain, and the first two years of Donald Trump's presidency have been marked by debates over US participation in multilateral organizations such as NATO.

The president never singled out OPIC for criticism, but his administration tried to set the agency's budget to zero in 2017. This step would not have disbanded OPIC completely, but it signaled the low priority placed on its role.

Axing OPIC would have been an ignominious end for the agency, which was established in 1971. Unlike traditional foreign aid models, which were based on providing grants, OPIC was intended to mobilize private sector investment in projects with sound business plans. It initially provided political risk insurance and loan guarantees only, though an investment funds program was added in the 1980s.

OPIC has built a reputation as a provider of high-quality financing. It is often sought after as a partner for the endorsement that its high standards are perceived to bestow upon a recipient, and its worldwide exposure topped $23 billion in 2017 and 2018 (with Asia accounting for more than $3.5 billion in both years). However, by 2018 the organization was straining under the weight of its legacy business model.

"The folks who work at OPIC are great, but it was a really burdensome setup," says Conor Savoy, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). "OPIC essentially created the political risk insurance market in the 1970s, and that was not an insignificant achievement. But its authorities were fundamentally the same as those that were passed in 1971, and it was time to do something new."

Dealing with OPIC has always been a tricky proposition for Asian GPs. Accepting the organization as an LP can mean a lot of extra work to ensure all stakeholders are comfortable with the investment structure. The most common criticism is that OPIC does not take equity stakes in a fund – it offers debt instruments only. This means that the DFI cannot anchor a fund; it can only provide leverage on top of prior equity commitments.

Meanwhile, the involvement of leverage can be a concern for other LPs. OPIC's commitments are typically structured intentionally similar to equity so that other investors' returns are not affected, but the covenants also normally have a clause giving priority for repayment to OPIC in emergency situations.

On top of that, the organization's US government ties can create headaches at the investment stage. OPIC's high environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards for portfolio GPs come with a US effects test, which prevents the agency from backing a company that could cause the loss of even a single US job. The review process can take weeks, and if OPIC ultimately refuses to invest, the GP must cover the cost using capital from other LPs. Such eventualities can be planned for, but they contribute to the perception among LPs that having OPIC as a partner is not worth the extra negotiation.

"There are a lot of LPs that just don't like leverage in general, but the other DFIs in particular hate OPIC," says the founder of one GP, who took a commitment from OPIC in a previous fund but decided not to approach the organization for his most recent fundraise due to objections from other investors. "It used to be more around the edges, but now a couple of DFIs have specific language in their side letters that says if you take our money you will not take leverage from OPIC."

Nevertheless, OPIC has been a significant player in Asia, making fund commitments in the past year to the likes of Quadria Capital and ADM Capital and completing investments in several infrastructure projects. Investors hope its successor can play an even larger role without the DFI's historic limitations.

All change

OPIC's transformation has been credited to its boosters within the administration – most notably Ray Washburne, a former entrepreneur and finance chair for the Republican National Committee that Trump nominated to head the organization in 2017. Washburne developed relationships with key administration figures such as Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, a close confidant of the president who joined OPIC's board in 2017.

High-profile initiatives such as a cooperation agreement with Japan's Bank for Investment & Cooperation (JBIC) were another part of Washburne's strategy to reposition OPIC as a tool for advancing US foreign policy objectives. As a result, the agency has gained increasing favor from the president: Trump publicly praised the JBIC agreement, holding it up as an example of promoting shared values with US allies, in a visit to Japan in November 2017 – less than eight months after proposing to defund OPIC.

The advocacy of Washburne and his allies came as their fellow policy makers were expressing fears about China's growing influence on the world stage, particularly in developing economies where the country has sought to position itself as a critical partner in the advancement of regional infrastructure.

"China holds itself up as a guardian of the developing world," says Bates Gill, professor of Asia-Pacific strategic studies at Australian National University. "Being a developing nation itself, it claims to have more sympathy and understanding of the challenges that recipient countries face than more powerful economically developed countries in the West."

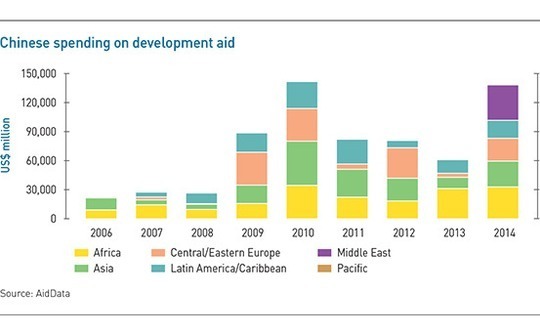

China does not release official figures on its provision of development finance, but AidData, a research lab at the College of William and Mary, conducted a five-year study to capture all officially-financed Chinese development projects between 2000 and 2014. The results show a surge in investments starting in 2009, when financing reached nearly $90 billion, more than the previous three years combined.

Development spending has remained above $60 billion in every year since; over the entire period China committed $354 billion worldwide, compared to US official aid spending of $395 billion. These figures are not directly comparable to OPIC's worldwide exposure, since they represent direct government investments rather than loan guarantees and risk insurance, but they help to illustrate the Chinese government's commitment to providing development aid.

Chinese financing has been welcomed by many recipients, particularly after the launch of OBOR, which encompasses infrastructure projects across 60 countries with an estimated price tag as high as $6 trillion. Borrowers' appetite is sometimes fueled by the fact that China is seen as a more accommodating partner than Western institutions that insist on high ESG standards.

But this apparently easy money comes with a high cost, with China often accused of structuring its loans to increase the chance of default and then using its leverage to force borrowers to turn over their assets to Chinese firms. Examples include a port in Sri Lanka, developed with Chinese financing, that was handed over to a Chinese state-owned company in 2017 on a 99-year lease.

The fallout from such accusations has been highly damaging for China's image as a champion of the developing world, and recent moves by the country have sought to highlight its multilateral credibility. AIIB is one example: Despite perceptions that it is primarily intended to back OBOR projects, the bank stresses its independence and willingness to work with any partners in the development finance space.

"We are apolitical in the way we work, and that's part of our constitution – all of our project screening and selection decisions are made according to objective economic criteria to do with the bankability of projects, economic benefits, debt sustainability, and so on," says Danny Alexander, a vice president and corporate secretary at AIIB. "In common with other MDBs we also have strong environmental and social safeguards and anti-corruption provisions."

Building out

Ironically, while China attempts to back away from accusations of politicization, the US has leaned in to the potential of development finance for promoting its foreign policy agenda. The Better Utilization of Investment Leading to Development (BUILD) Act, which Congress passed and Trump signed last October, was expressly pitched as a means of modernizing OPIC in response to the rise of China and providing a nonmilitary means for the US to exercise its soft power.

"You never would have gotten the political support for this if they didn't feel some pressure because of China," says Savoy of CSIS. "But there were also a lot of people who were persuaded that, beyond China, this is just a good thing for the US to do from a geopolitical development perspective."

The primary effect of the BUILD Act is the replacement of OPIC with USIDFC. In addition to raising USIDFC's overall capitalization to $60 billion – up from $29 billion for OPIC – the new organization will be able to take equity stakes in projects and funds. USIDFC will also be allowed to take smart risks through local currency loans, first loss guarantees, and the provision of small grants. It will only be asked to show a "preference" for US investors, rather than a requirement as with OPIC.

The changes have the potential to make OPIC's support available to a much wider array of GPs, most notably through the equity investment channel. In addition, USIDFC may have an easier time co-investing in companies alongside GPs and working with other DFIs to support infrastructure projects.

However, market watchers urge caution, as many of the details about how USIDFC will function have yet to be worked out. Before the new DFI officially opens in October, it will need to determine how its equity investments will function. This is particularly challenging because, while debt is an often-used tool by US government entities, equity has never been employed before.

Even in draft form, USIDFC's remit points to a much more coherent approach than that of OBOR, which is more of a broad, decentralized policy statement. Capital has been mobilized from a diverse group of players, mostly government-backed financial institutions and international multilateral investors, but there is no central authority designating which projects or companies will receive funding and how it will be provided. Implementation is largely left to individual investors.

By contrast, USIDFC is fundamentally a continuation of OPIC with the same basic goal: mobilizing private capital to effect development goals and create jobs for US companies. Unlike OBOR, it is designated as a market-based solution that can lend to small and medium-sized enterprises in emerging markets, as well as supporting large infrastructure projects. It should be a more palatable approach for GPs and private companies in the targeted regions.

"Once you take advantage of the authorities that are in the BUILD Act, you're really talking about a sea change. I've heard from other DFIs that if this is implemented well, it could be the gold standard for development finance," says Savoy.

Policy prop

Despite the optimism around the BUILD Act, the circumstances of its passage makes it clear that the administration expects USIDFC to lead to some kind of foreign policy benefit.

How that expectation will manifest in the new organization's operations is not yet known, but a common speculation is that recipients could face pressure to remove equipment from Huawei Technologies or ZTE Corporation from their infrastructure. This would represent a departure from OPIC's historically apolitical approach, but in light of China's perceived aggressive approach to development finance the US could well decide to take a more activist role itself.

ESG standards at USIDFC are another area of uncertainty. There are concerns that the high levels of compliance demanded by OPIC might be diluted by political meddling. This could result in support going to recipients previously considered unworthy such as companies with ties to dictatorial regimes or projects in the districts of politicians with whom the US seeks a closer alignment. If US commitment to ESG slips, it could undercut the efforts of other DFIs that seek to maintain high standards.

While there is little consensus around how these questions will be answered, observers in Asia broadly agree that the development finance landscape is entering a period of increasing polarization, with the US and China aiming to create strategic advantages by providing financial support to the right projects or people. Recipients could benefit as these two well-resourced rivals compete to earn their favor, but the fear is that financing will end up going not to those who deserve it but to those who can play the game the best.

"There's never really been untied aid. Japanese aid always came with a requirement to use Japanese resources, US aid has been largely linked to anticommunism, and Chinese aid may come with a requirement to remove recognition of Taiwan or allow basing rights for Chinese ships," says Parag Khanna, founder and managing partner of advisory firm FutureMap. "There are just differing degrees and different kinds of politicization by different actors."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.