Asia leveraged finance: Institutional aspirations

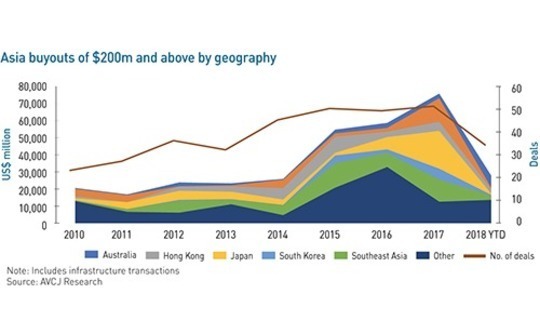

PE firms can obtain financing for leveraged buyouts in Asia on increasingly favorable terms, but this doesn’t necessarily point to institutionalization – or at least, not yet. For now, banks still lead the way

Australia's leveraged buyout market changed comprehensively – and perhaps permanently – last summer when Pacific Equity Partners and The Carlyle Group acquired iNova Pharmaceuticals for $930 million. HPS Investment Partners provided the bulk of the debt, marking the first sizeable transaction involving a credit fund and a unitranche-like structure.

Since then HPS has added to its tally, supporting nearly a dozen transactions. It is said to have deployed around $2 billion into Australian credits that are held by the firm's funds rather than syndicated to third parties. The "stretched senior" model combines senior and mezzanine facilities into a single debt piece, simplifying the process for PE firms because they don't have to negotiate with multiple counterparties across different tranches. Commercial banks, previously the go-to senior lenders for buyouts, now meet the super senior revolving credit needs of these deals.

With other non-bank lenders – from ICG to Partners Group – also active in the unitranche space, Australia appears to have followed the US and Europe in making the transition from a bank-led to an institutional market. But Gary Stead, a managing director at HPS, is wary of describing the change as irreversible. Australia, much like other markets around the world, has seen credit funds offer increasingly aggressive terms on deals. The party cannot last indefinitely.

"Money has crowded in and money can get pulled out pretty quick," he says. "There has been dilution in terms and pricing. Interest rates in Australia are at all-time lows, but they will eventually start to creep up and what pressure does that place on borrowers' businesses? That's why we don't just meet market terms but look at everything on a deal-by-deal basis and form a view on the risk and the terms."

A time of plenty

Several bankers and debt investors attest that, at least for the time being, borrowers in Asia have never had it so good. While the US and Europe have seen some minor repricing of risk in recent months, competition for financing mandates is intense. "I think banks are as aggressive as they've ever been because there isn't enough volume flowing through the market," says Lyndon Hsu, global head of leveraged and structured solutions at Standard Chartered.

The shortage of deal flow can, in turn, be tied to competition among the private equity firms themselves. Dry powder is at record levels, which means a lot of money is chasing the same transactions and driving up valuations to points that are beyond the limits of disciplined investors.

"Most of the clients I speak to are spending most of their time trying to find proprietary deals that their 10 other competitors aren't working on," adds James Horsburgh, head of leveraged and acquisition finance for Asia Pacific at HSBC. "Right now, from a financing point of view, the conditions are super receptive to doing big deals. Some clients, especially those with financing experts in their teams, say they look at deals and worry about the financing later because they're confident on leverage achievable."

This willingness to finance deals in Asia should not be confused with a broader institutionalization of the region's leverage markets. Several of the non-bank lenders active in Australia are looking for similar opportunities elsewhere in the region, but regulatory uncertainty and market access remain significant obstacles. And in the absence of covenant-lite terms within Asia, some banks are taking a covenant-loose approach to win business.

"The view is that in any number of jurisdictions the insolvency regime is corrupt, inefficient, doesn't exist or is unpredictable. They can't work out what the outcome would be, so they assume worst case," adds Alexander McMyn, a partner with Hogan Lovells in Singapore. "They recognize they have to get to Asia at some point, but they are constrained by the medium-term investment horizons of their funds. It is hard to say to investors that now is the time to generate more unpredictable returns in Asia."

Australia is exceptional because its insolvency regime and legal structures bear similarities to European markets, and most importantly, they are tried and tested. It also differs from other Asian jurisdictions in that the local banks, while disciplined and conservative on credit, are perceived by some as lacking a competitive edge. For funds that can offer more flexibility, this creates an opening.

Contrast that with Japan, which last year saw Asia's largest leveraged loan raised for the region's largest private equity-led buyout. The JPY2 trillion ($17.6 billion) acquisition of Toshiba Memory Corporation is said to have been supported by more than $7 billion in debt, and a club comprising Japan's leading commercial banks covered the entire package. Korean banks, like their Japanese counterparts, make the most of their relatively low cost of capital to crowd out international competition.

The Taiwan effect

Elsewhere in the region, the playing field is more even, although the Malaysian and Singaporean banks are known for aggressively pursuing deals in their home markets. As has been the case for several years, the Taiwanese banks constitute a random factor – and their willingness to offer competitive terms has resulted in situations where financial sponsors forgo a US-style structure.

"Term loan B-style structures are cov-lite but the pricing is expensive. They can also be inflexible on fees and some other terms," says one pan-regional fund manager. "When it comes to borrower-friendly terms, no one beats the Taiwan banks. The pricing is low, they are flexible on covenants and give you a lot of headroom. They offer many things Western banks won't give you."

The fundamental characteristics of a US term loan B cannot be matched in the Asian markets: incurrence covenants, which are only tested when the borrower takes certain actions, such as issuing new debt or engaging in M&A; flexibility on dividend payments and investment in capital expenditure; a bullet repayment on maturity after seven years instead of gradual amortization; and tight pricing.

A standard Asian bank loan package might be expected to feature a shorter tenor of five years, amortizing debt and multiple maintenance covenants linked to leverage levels, interest rate expenses, and cash available to make repayments on outstanding debt. If these covenants are breached at any point, the sponsor would have to spend a lot of time and money agreeing a reset on more favorable terms to the lenders or, at worst, face losing control of the portfolio company.

However, the covenants approved by some banks are so loose they could only be breached in extreme circumstances. For example, there is said to be a lot of flexibility in terms of a company's ability to make acquisitions without creditor permission or dispose of assets without using the sale proceeds for prepayment of the loan. In addition, the headroom – the amount by which pro forma leverage can exceed the ratio in the covenant – afforded to companies goes well beyond the 30-35% that in recent years has become the industry standard. International banks, by contrast, tend to be more disciplined.

"We always set covenants off a banking base case and we diligence how realistic the base is," says HSBC's Horsburgh. "Then there is the question of how you structure covenants. We are focused on the detail of how you define EBITDA and that the drafting of financial covenants is appropriate."

Private equity firms have also become more adept at playing the market. One advisor recalls working on a Southeast Asia deal last year where the sponsor ran a competitive process for the underwriting mandate and selected one international bank alongside a handful of Taiwanese lenders. The former had trusted execution capabilities, while the latter were there to ensure the best possible terms.

"Whenever the international bank objected to something, the sponsor would say we must have this position, let's put it to a vote among the banks," the advisor explains. "Every time, the international bank voted no but the Taiwanese banks voted yes, so it was swept through. It nearly cratered the deal because there was a contractual obligation for the international banks to be involved. The international bank was unhappy with the situation, but the sponsor didn't care because there's so much cash around."

Nevertheless, there are limits are to how much these lenders can commit to a deal. When Affinity Equity Partners acquired Trimco from Partners Group in January for an enterprise valuation of $520 million, Taiwanese banks provided the entire senior debt package "because they pushed terms to a level where none of the international banks could live with it," according to one banker who looked at the deal. For a transaction with $1 billion in debt, a broader collection of lenders would be necessary.

Taiwanese banks have their own comfort zones as well. Trimco is a Hong Kong-headquartered garment label manufacturer that generates a lot of its revenue from within Asia. Moreover, Affinity is the company's third consecutive private equity owner and Taiwanese lenders are said to have been involved when Partners Group acquired the business. This familiarity with the industry, geography, and Trimco itself may have encouraged the banks to be more aggressive.

A widening field

For larger transactions that have a relevant angle, Chinese banks are now prominent participants. Two leveraged buyouts from either end of last year – The Carlyle Group-CITIC Capital-CITIC Group acquisition of the McDonald's business in mainland China and Hong Kong and The Blackstone Group's purchase of ShyaHsin Packaging – were supported by Chinese and Taiwanese lenders.

When bidding for previous deals, Chinese lenders are said to have been accommodating on tenor, leverage, pricing, and covenants: seven-year packages; leverage multiples of 5-5.5x forward EBITDA; upfront fees of 1%, whereas most other banks would normally start at 2.5%, because there is limited syndication; and a lot of capital structure flexibility. Meanwhile, the quantum of capital available from a single lender could be in the region of $500 million.

Several bankers and advisors claim Chinese banks are now becoming tighter on terms, although patriotic lending for outbound deals is still a characteristic of the market. Bank of China recently committed $700 million to the $1.4 billion acquisition of Australia's Sirtex Medical by CDH Investments and China Grand Pharmaceutical & Healthcare Holdings. Meanwhile, the $17.6 billion buyout of Yum China didn't come to fruition, but it would likely have drawn strong interest from local and international lenders.

"The Asian bank market is very much akin to what the European bank market was in 2005, with a well-known set of parameters and terms that banks seldom stretch. However, with different pools of liquidity competing for deals, you can get differentiating terms," says David Irvine, a partner at Kirkland & Ellis. "In some transactions, there is a trade-off. A sponsor might want confidentiality and speed of execution, which means it will compromise on competitive tension and agree to less attractive pricing and terms. But if it's a publicly announced deal with a long gestation period, the sponsor can maximize competitive tension amongst, or within, the pools of liquidity and deliver the best available financing terms."

While term loan B has yet to arrive in Asia, Irvine notes that companies can access these differentiating terms by going direct to the US or Europe. KKR was the first to do it for an Asian buyout with the privatization of Singapore-listed container manufacturer Goodpack in 2014. Term loan B structures subsequently supported the acquisitions of Hong Kong-headquartered Vistra Group and Philippines-based SPi Global, and they also featured in several financings and refinancings in Australia prior to the rise of unitranche.

The industry is still waiting for a US term loan B breakthrough on a China deal. The Blackstone Group financed the privatization of US-listed Pactera, also in 2014, through a high-yield bond in the US, but the buyers were mostly Asian institutions. It all comes back to whether international credit funds can get comfortable with the jurisdictional complexities.

"If you are looking at a traditional US-style term loan B, the investors would need a familiar jurisdiction for workout scenarios and clear visibility into the collaterals. That would be tough for China deals because you can't get a pledge of any collateral onshore," says Desmond Tang, head of financial sponsors coverage for Asia Pacific at Natixis. Uncertainty over currency controls and leakages due to the withholding tax levied on dividends coming out of China are added complications.

Pactera got done because the company provides IT outsourcing services to multinationals, which meant the customer base was familiar and a lot of revenue is in US dollars. Vistra and SPi Global have similar commercial characteristics – as do the clutch of private equity-owned Indian IT outsourcers that obtain debt funding through the US markets, despite India presenting much the same onshore-offshore challenges as China.

Baring Private Equity Asia used a high-yield bond to take out a leveraged loan for Hexaware Technologies in 2016 and Blackstone did the same a year later for Mphasis. Earlier this year, Baring is said to have taken the market forward by putting in place a bridge financing and bond structure to support the acquisition of Intelenet, another Indian outsourcing business owned by Blackstone. It ended up losing the deal to a French strategic player.

However, India still entered new territory in 2018 with the acquisition of medical devices manufacturer Healthium MediTech by Apax Partners. This was the first unitranche financing, in the purest sense, for an Asian leveraged buyout. While stretched senior deals in Australia are often referred to as unitranche, they rely on traditional intercreditor agreement whereas US unitranche transactions are based on agreements among lenders (AALs) to which the borrower is not party.

Not if, but when

The outstanding question is when do these structures graduate from highly selective, situational use to become part of the mainstream in Asia. One significant change in the last few years is more institutional credit investors have people on the ground looking to generate business as opposed to covering the region out of Europe or the US. At the same time, an increasing number of global and regional sponsors are interested in seeing the more flexible structures they have used elsewhere take hold in Asia.

Given this favorable demand-supply dynamic, it's just a matter of time before institutional structures take hold, but it will be a gradual process. The sheer volume of liquidity in the bank market – and the competitive flexibility this encourages – is a factor, with one Hong Kong-based non-bank lender noting that in many cases "credits are not appropriately priced, and sponsors can get stretched leverage." It must be the right credit on the right terms, and perhaps most importantly, in an acceptable jurisdiction.

"You see deal structures where there is a Singapore holdco owning shares in a business that has operations in various markets around Asia," adds Stead of HPS, which has been shown Australia-style stretched senior opportunities in other Asian markets but has yet to execute on one. "You can take collateral over the shares, but it's still a subordinated piece of paper – you don't have direct security over the assets in the business. If you have to enforce you can take the shares, but what must you do to take the assets in country? In many markets, no one knows. So how do you then price that risk?"

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.