PE and tech investment: The late show

Private equity firms are participating in late-stage rounds in Asia’s technology space as they look to gain a toehold in start-ups with the potential to transform economies. But do the valuations make sense?

Pinduoduo went public last week with a market capitalization of more than $25 billion, catapulting its 38-year-old founder and largest shareholder into the upper ranks of China's rich list. The company's quirky combination of social media and e-commerce – users are incentivized to share details of products they want to buy with friends – is seen as posing a nascent challenge to the likes of Alibaba Group. But three years ago, the company did not exist.

The speed at which Pinduoduo has gone from zero to RMB262 billion ($38.5 billion) in gross merchandise volume (GMV) and 195 million monthly active users says everything about the dynamism of Chinese internet-enabled technology. The condensed timeframe from establishment to IPO also explains why PE firms are increasingly willing to dabble in this space.

Investors weaned on buyouts or growth capital plays for relatively mature companies recognize the transformative role pre-profit start-ups are playing in the economy and they see an expedited path to liquidity. The question to which no one knows the answer – though it has been asked for years – is how much longer the party will last. As PE firms join assorted other capital providers in late-stage rounds at ever higher valuations, who will be left to rue the fact they took on too much risk?

"Many companies don't have financial models for PE guys to run their due diligence, but we keep getting calls from private equity investors, asking about our companies. And they are getting interested before the pre-IPO rounds. It doesn't matter if there's no profit. If a company has $10 million in revenue they want to take a look," says Chuan Thor, founder of Chinese early-stage VC firm AlphaX Partners. He notes that Series C rounds of $75 million and above are now typical PE targets.

Pinduoduo is a classic case of how valuations can escalate once a business gets traction. It also stands out as an example of how private equity investors can struggle to get access if they don't know the right people, can't move fast enough, or fail to outmuscle well-resourced strategic and financial competition.

By the time of its $100 million Series C round in 2017, Pinduoduo was said to be worth $1.5 billion. This became $15 billion in March when Tencent Holdings and Sequoia Capital accounted for the bulk of a $1.37 billion Series D round. Tencent's individual contribution of $988.8 million comprised cash and strategic support, while Sequoia participated through its $8 billion global growth fund.

A rising tide

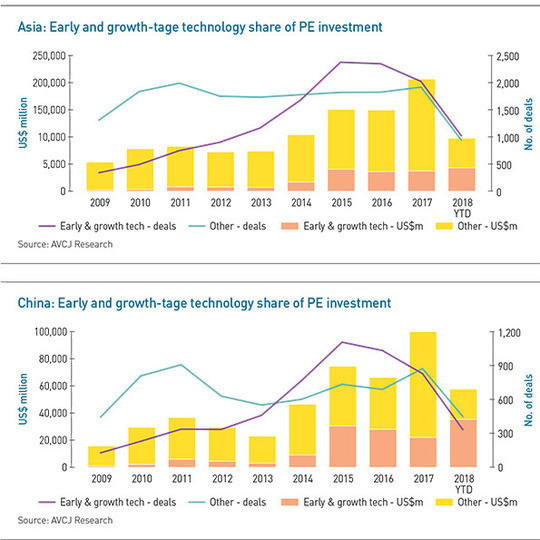

Needless to say, private equity investors and their counterparts have found numerous other ways to put money to work. Of the $205 billion committed to private market deals in Asia last year, 18% went into early and growth-stage technology deals, twice the share in 2013, according to AVCJ Research. In China, it rose from 13% to 22% (it was 42% in 2016) over the same period, while India has gone from 14% to 40%.

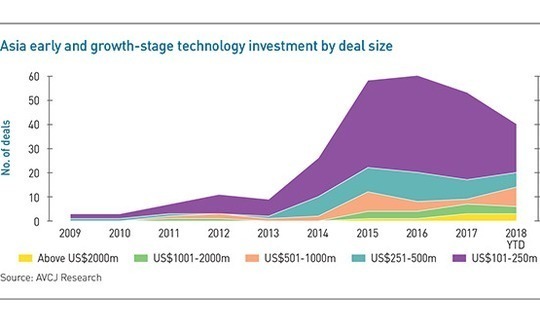

Much of this capital has gravitated towards large rounds for unicorn start-ups valued at $1 billion or more. In 2013, there were just two funding rounds worth $250 million and above. Last year, the total was 17, seven of which were $1 billion-plus deals.

The main reason early and growth stage technology accounts for 44% of the $96.9 billion invested across the region so far this year is Ant Financial. The Alibaba Group affiliate closed its Series C round at $14 billion in June at a valuation of $150 billion – the largest single capital raise by any company globally. PE participants included Warburg Pincus, The Carlyle Group, Silver Lake and Primavera Capital Group. They were joined by various hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, and pension funds.

"Technology is rapidly re-shaping consumer behaviors and upgrading business models, and we are committed to supporting innovation and entrepreneurship," says X.D. Yang, Asia chairman at The Carlyle Group. "We believe the sector has a lot of potential for years to come, particularly in China as consumers increasingly migrate their time spent towards mobile and businesses continue to innovate by harnessing big data and the latest technologies that can enhance their competitive position."

The private equity firm entered the late-stage technology space in 2014, backing online reading business China Literature and classifieds site Ganji. It was necessary to get comfortable with some of the realities of in-demand internet deals: high valuations, limited shareholder rights and board representation, and an uncertain commercial outlook. But these bets paid out as Ganji merged with listed rival 58.com in 2015 and China Literature went public in Hong Kong last year.

Carlyle has completed eight more technology deals, taking its total capital committed to the space to $2 billion. Apart from Ant Financial, the GP's flagship Asia fund has backed Baidu financial services spin-out Du Xiaoman, online retailer JD.com's logistics unit, and real estate portal Fang.com. Auto services platform Tuhu and vending machine provider Ubox have been backed through other funds.

There appears to be a philosophical divide between the pan-Asia buyout players regarding pre-profit internet companies. The likes of Baring Private Equity Asia, Affinity Equity Partners, and CVC Capital Partners have so far stayed away, while PAG Asia Capital, TPG Capital, and KKR have proved themselves willing participants in the last three or four years.

Some of these investments have involved control – for example, PAG and KKR are majority owners or Chinese online dating service provider Zhenai and Korean e-commerce player Tmon, respectively – but even in those that do not, GPs claim they can get reasonable governance rights. Terence Lee, a director with KKR, notes that despite coming into the Series D round for Indonesian ride-hailing and delivery business Go-Jek, the firm got a board seat and has a reasonable amount of influence.

The aim is to make investments that are similar in nature to the growth deals in traditional industries that have long been part of the KKR strategy in Asia. As part of that criteria, a company needs to be proven because high levels of risk around technologies and business models are problematic. This could be achieved directly through performance data or KKR will identify analogous companies in more developed markets and assess whether its target is likely to follow the same growth trajectory.

"We try to underwrite things much like we do in other situations. This means we're assessing opportunities by using proper data and a proper view on the company, as well as understanding its prospects and the prospects for the sector it is in. This comes in addition to our analysis of a company's financials of and what kind of returns you can get," says Lee. "The big picture element is part of the process, but we would never bet on a company to do well solely because it's in a sector that is growing 20% a year."

Talking terms

A private equity firm's ability to access enough information in time to conduct robust due diligence and its chances of securing a favorable arrangement on governance often rest on the popularity of the target company. The more investors are queuing up to get into a funding round, the less their collective leverage over terms.

"Founders of these top-tier, in-demand companies are not beholden to traditional conventions of what a standard preferred equity round should look like. They want to preserve control and dictate economic terms, and they are willing to rewrite the rules of the game to achieve this end" says Thomas Chou, a partner at Morrison & Foerster. "Prestigious investors have had to compete viciously for allocation in these companies. Unfortunately, the ability for these investors-in-waiting to hold the line is only as strong as their weakest link. When one investor capitulates to secure their membership in the club, others will inevitably follow."

The ideal downside protection for a private equity investor as a minority shareholder is a money-back guarantee with a pre-agreed return on top. For example, Bitmain, a five-year-old company that has become the dominant global player in manufacturing chips for bitcoin mining, raised $400 million in Series B funding earlier this year at a valuation of $12 billion. Investors will be fully redeemed, plus a 10% IRR, if there is no IPO within five years, according to a participant in the deal.

In addition to redemption provisions that are triggered by a failure to facilitate an exit for investors, investors increasingly negotiate valuation adjustment provisions that would reduce the effective pre-money valuation of the company for their investment if a company falls short of various performance milestones. Some of these are based on certain financial metrics, such as GMV or EBITDA, while others could be tied to restructuring part of a business, getting a license, or even a material adverse change in the market rather than in the portfolio company.

"In China, redemption clauses are typically more investor-friendly than in the US," says James Lu, a partner at Cooley LLP. "Redemption could easily be triggered before the end of the typical four or five-year timeline. Some companies copy and paste these redemption provisions with hair triggers, and when things go bad, people start inspecting them closely. I've definitely seen companies get caught off guard."

He adds that it's usually clear from the terms how much leverage a founder has. Apart from better economics, backers of a weakened company might get more of say in how decisions are made at the board and operating levels. There might also be additional restrictions on founder share transfers, as well as on drag-along rights that allow investors to dictate the timing and pricing of a sale. On the flip side, popular start-ups place limits on investors, such as preventing share sales to or even investment in competitors of the company.

Closed-door redemption negotiations are said to be underway involving several Chinese unicorns that have failed to live up to their promise. Meanwhile, the seeds of late-stage investor frustration are there for all to see in the stock prices of several companies that have listed in Hong Kong over the past 12 months.

Zhong An Insurance, an online-only insurance business created by the founders of Alibaba, Tencent, and Ping An Insurance, and Ping An Healthcare & Technology, operator of healthcare-focused mobile app Ping An Good Doctor, were previously two of China's most in-demand unicorns. They raised pre-IPO rounds of $931 million and $500 million, respectively, in 2015 and 2016, and then the SoftBank Vision Fund followed up with a $400 million investment in Good Doctor.

Zhong An went public in September 2017, pricing at the top end of its indicative range, but it is now trading at a 35% discount to its IPO price. Ping An Healthcare, which began trading in Hong Kong about seven months later, is down nearly 12% on its offering price. Pre-IPO investors are said to be underwater on the former and at par on the latter.

It remains to be seen what happens to Xiaomi, the Chinese mobile phone manufacturer that in late 2014 achieved a valuation of $45 billion, briefly becoming the world's most valuable technology start-up. The company listed in Hong Kong with a market capitalization of $54 billion – below the mooted target of around $100 billion – and is currently trading at a modest premium to its IPO price.

These are examples of high-profile businesses that have yet to capture the imagination of the public markets. Investors could list a string of other IPOs, Pinduoduo among them, to which the response has been more favorable. But the currently sub-optimal outcomes on the Hong Kong bourse do underline the difficulties private equity investors face in identifying the right entry point.

"We only do one or two of these investments a year and we only invest in proven companies, and the challenge is getting in," says Vincent Huang, founder of China-focused Juntong Capital. "There is so much demand right now. By the time these deals are well known in the market it is too late. You must go into an earlier round, but often these rounds aren't open to outside investors."

That observation captures the PE dilemma: Invest too early and you risk backing a company that will be outmaneuvered by fleeter-footed competitors within 24 months; move too late, and even though a business achieves sustainability, it never lives up to the valuation you paid to get into the deal. When investors try to find the right balance against a backdrop of too much capital chasing too few deals, it creates the fevered behavior that currently characterizes the market.

Cyclical or structural?

Asked whether the phenomenon is cyclical or structural, most industry participants say it is a bit of both. China's online retail market is expected to increase in size from RMB6.1 trillion in 2017 to RMB10.8 trillion in 2020; mobile payment transaction volume is projected to see compound annual growth of 35.9% over the same period, reaching RMB388.6 trillion; and every vertical of the internet economy is set to benefit from an increasing willingness among consumers to pay for services.

Transformative business models are emerging from this melting pot, facilitating the development of "companies that can immediately disrupt entire industries – they can become profitable faster and get scale quicker," as AlphaX's Thor puts it. But no matter how many strong players are established across e-commerce, financial technology, or healthcare services, investments predicated on exit valuations comparable to the market capitalization of a JD.com don't necessarily make sense.

"Valuation is a separate issue from the fundamentals – you can overpay for any business," says Yar-Ping Soo, a partner at Adams Street Partners. "If an investor looks at the fundamentals and thinks that with such rapid growth any valuation would be justified, they are going to make bad investments. This is more worrisome for us than PE firms that look at a business and say, ‘It's not making money today, but it does bring certain value to its constituents that will allow it to succeed in the future.'"

Few LPs would pick faults in a 3x return, even if it is from an essentially passive minority investment in an internet-related business. Indeed, a substantially marked-up position in a unicorn can be a useful calling card for GPs on the fundraising trail.

"It's a lot easier to raise a fund if you've invested in Ant Financial," says one China-based manager. "I will get more questions about why we paid 8x earnings for a traditional consumer business than any of those guys will get on why they went into a non-profitable governance mess that has massive related-party issues at a valuation of $100 billion. LPs are indirectly rewarding people for making these investments."

Should these investments go wrong, however, GPs can expect a barrage of questions about why they backed unproven companies in volatile industries, and without any real means to influence the outcome or control their mode of exit.

As it stands, mixed messages abound. Some industry participants say investors have become concerned about elevated late-stage valuations and are pulling back. Others continue to tell stories of ill-disciplined behavior: GPs taking shortcuts on due diligence and backing companies based on the quality of the existing investor base; bankers advising clients to buy in at $40 billion because a $60 billion valuation on IPO is assured; and the overarching sense of history repeating itself.

"As long as the music keeps playing, people feel they must keep on dancing, and no one knows when it will stop," says Juntong's Huang. "But we've seen billion-dollar companies vanish overnight before and it will happen again."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.