Secondaries: A cautionary tale

Cracks have appeared in the secondary transactions through which Standard Chartered Private Equity had sought to secure its future, underlining the challenges for investors of bank-led deals

On November 1 of last year, Joe Stevens' decade-long career with Standard Chartered Private Equity (SCPE) came to an abrupt and unhappy end. Since 2013, he had helped put together $2.3 billion in secondary deals designed to remove PE assets from the bank's balance sheet while latterly working on a spin-out of the GP. But Standard Chartered axed the spin-out, telling Stevens it would proceed with an orderly wind down and he would not be required to oversee the process.

To LPs that backed those transactions, the termination was a shock. They felt they had entered into agreements with Standard Chartered in good faith – with a clear understanding as to how and by whom assets would be managed – only to have it thrown back in their faces. This was not the deal they had signed up for, and the contracts said as much. In the ensuing chaos, at one point it seemed possible that a unique secondary market exercise could come crashing down in a wave of litigation.

A formal solution has yet to be reached: LPs could still use the key person event triggered by Stevens' dismissal to remove SCPE as manager of the secondary portfolios. Indeed, the LPs, investment professionals and advisors who spoke to AVCJ cited the lack of an agreement – though they hope there will be one – as a reason for keeping discussions off the record. They describe the situation as tense.

The bank, meanwhile, is scrambling to recover it. "We have got plans to realign the portfolio. We have some third-party stakeholders in terms of co-investors and others who are relying on our exercise of good oversight and very focused on getting the very best economic results for ourselves and our stakeholders. That is a small business and we will migrate to a new format in a year or two," Standard Chartered CEO Bill Winters told media last week on a trip to the Middle East.

Steps have been taken to keep the team together and assuage fears that individuals would depart in the wake of the failed spin-out. Sources close to the bank also say that capital will be made available from the balance sheet for new deals – although investments will be made selectively – and further secondary transactions will be explored. Moreover, the idea of creating an independent GP is still on the table. It remains to be seen whether investors are willing to participate.

"Put yourself in our position. We did have a positive outlook on the idea of doing a second transaction with them," says one LP with exposure to the secondary portfolios. "Today, the issue for us is, are the assets we have invested in going to be properly managed and exited, not whether we care about the team spinning out. If my colleagues proposed a deal with SCPE involving a spin-out, I might veto it."

None of the parties involved is entirely blameless: not the bank, which took action without considering the consequences; not Stevens, who perhaps pushed too hard for the spin-out due to concerns that the team would break up; and not the LPs, who arguably could have done more to understand the dynamics of the situation. Above all, the situation underlines the difficulties presented by secondary transactions, and how these are magnified by internal politics when dealing with banks.

"Banks make decisions based on what is in the best interests of the P&L account at that point in time," says Juan Delgado-Moreira, managing director at Hamilton Lane. "Those decisions often have nothing to do with private equity and whether the bank thinks it is an attractive asset class, and everything to do with their stock price, their management and their balance sheets, and their capital adequacy ratios."

Signature secondary

Regulation was a key consideration when, around 2012, Standard Chartered decided it could no longer support a principal investment business off its balance sheet. This was not an unusual view; a number of banks have spun out assets for similar reasons. However, the SCPE situation was unusual in two respects. First, the bank decided against a complete spin-out of the PE unit, recognizing the role a captive GP could play in building up the Standard Chartered brand among companies in emerging markets. Second, there were a lot of assets to move and limited time in which to move them.

This led to five transactions across four new limited partnerships, completed between 2013 and 2015, in which secondary investors took out more than 40 bank positions, with the captive GP retaining management responsibilities. The SCPE team took a minority interest in each partnership. Management fees and carried interest – lower than 2% and 20% – accrued to the bank with an agreed portion going to the team. It left the bank with balance sheet assets that now stand at approximately $2 billion, including $600 million in a real estate business that is in the process of being sold off.

Goldman Sachs bought the first tranche and Coller Capital led the second and third, bringing in GIC Private and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) as co-investors in the third. Tranches four and five, which involved a single limited partnership, featured LGT Capital Partners, Partners Group, Goldman Sachs and Blackstone Strategic Partners, followed by Rothschild and Unigestion. Standard Chartered took a 20% stake in the last partnership.

Tranches four and five were supposed to be a staple, with participation in the secondary conditional on committing to a new primary vehicle, but preparations could not be completed in time. Still, there was talk of a new fundraise in 2016 or 2017; the bank was supposed to participate as an LP and hopes were expressed that several investors in the secondary deals could be persuaded to re-up.

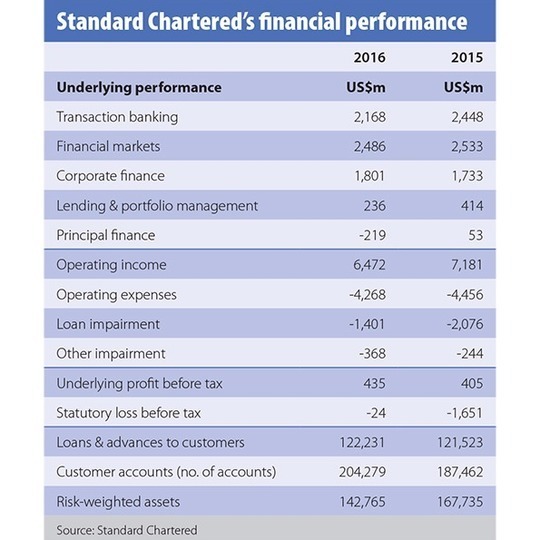

Standard Chartered's plans changed last June with a decision to exit the PE business, driven in part by poor performance within the portfolio. The principal finance division had contributed $53 million of income to the bank in 2015, but this turned into a $216 million loss in 2016 as investments in Nigeria and Southeast Asia struggled, particularly those with oil and gas industry exposure.

"At the time, banks across the world were focused on making sure their tier-one equity ratios were above what was required by regulators," says another source familiar with the situation. "The view was that as long as the team was still going to be part of Standard Chartered, the bank would continue to pay salaries and cover the expenses of the private equity business. If there was going to be a spin-out, it could be addressed."

One way to make up the shortfall was for the bank to provide soft working capital for a few years. This was nixed due to concerns that it might violate US regulations as to what kind of relationship Standard Chartered could have with the GP once it was independent.

Attention then switched to raising a new fund, but existing investors were mindful that it shouldn't be too much, given the team's responsibilities to the secondary tranches. A staple deal, comprising $500 million in legacy assets and $250 million in fresh capital was discussed. However, this wouldn't fully close the gap so it was suggested the bank sell working capital to the team up front and at a discount. Negotiations are said to have faltered over how big the discount should be.

One LP recalls a meeting around this time with Stevens and Bert Kwan, SCPE's head of Southeast Asia who was also involved in the negotiations but to a lesser extent. "They were saying a spin-out was a couple of months away, that they were in final negotiations with the bank," the LP says. "But they were also a bit cryptic, saying that the bank was isolating them and seeing them as a separate entity. Acrimonious would be the wrong word, but it seemed a bit weird."

Nevertheless, this did not prepare him for what followed as the deal fell apart. Some LPs learned of Stevens' departure via the media; others found out in advance of that, but not by much. Kwan was terminated shortly afterwards. The two individuals who were key persons or super key persons on most of the secondary tranches – and who were the primary point of contact for the LPs – had been removed. "We were dumbfounded," says one LP.

Conflicts of interest

When AVCJ covered the SCPE secondary deals last year, various investors expressed concerns about alignment of interest in situations where the assets spin out but the team does not. There are routine measures for minimizing potential conflicts between a GP's fiduciary responsibilities to the new third-party investors and its obligations as a unit of a bank, such as having the management team invest in the fund. Beyond that, investors must believe in the quality of the team and its ability to stay together.

Lucian Wu, a managing director at HQ Capital, said at the time that he is most comfortable with clean spin-outs because teams tend to be more motivated. If they stay part of the institution, even with some skin in the game, "There is no sense of ‘If I don't make it I'm going to die.'" His views on the matter have not changed. "As long as the GP sits inside the bank it's clear who the ‘real' decision maker is and how interests could be misaligned. Interest alignment is key to me in any secondary transactions, just as important as the quality of the assets," Wu says.

These sentiments are echoed by Andy Nick, a managing director at Greenhill & Co. He acknowledges that retaining some ties to the former parent can be helpful, but only as long as the economics are aligned in favor of the team. "I think investors are served best if the economics of the GP reside with the spin-out team exclusively or the majority of the economics sit with the team that is going to be managing the assets, versus somehow accruing back to the former parent," Nick says.

While GP replacement is an option in the case of SCPE and some LPs are said to have reached out to other private equity firms for price quotes, there are obstacles to pursuing this course of action. First, the management fees on the secondary portfolios are below market rate; a replacement GP would likely charge more. Second, the portfolio is geographically diverse, covering Asia, Africa and the Middle East; few, if any, managers offer similar coverage, so it would be necessary to break up the portfolios.

Rather, the focus has been on finding a solution with Standard Chartered, and reaffirming an alignment of interest is central to these efforts. LPs typically have three priorities in these situations: no more surprises; stabilization of the team, ideally so there is little or no change in representation on portfolio company boards; and, particularly in the case of SCPE given the bank's goal to give up principal investment, a longer term plan for the business that ensures the assets will be properly managed.

Standard Chartered has awarded bonuses to team members in order to secure their immediate loyalty and LPs say the percentage of carried interest that goes to the team has been increased and pushed out so that payments start in two years. According to sources close to the bank, the incentives are comprehensive and structured with a view to making the business more valuable in the long term. There are currently approximately 50 staff across private equity and real estate, led by 10 managing directors, and that is seen as an appropriate number for the size of the portfolio.

The narrative coming out of the bank is that the spin-out proposal put on the table last year did not represent a satisfactory solution for the three stakeholder groups. There were also attempts to push it through too quickly, leading to a breakdown in communication. Now the process will be discussed in more measured terms and with greater transparency. And with a slimmed down team, getting market fees on a combination of another secondary deal and some primary capital would cover costs.

While the LPs that spoke to AVCJ do not wholly dispute this view, they add two caveats. First, Standard Chartered has no option but to be transparent given what has gone before. Second, there are questions to which they will probably never get accurate answers. For example, the question of whether Stevens pushed too hard for the wrong deal or was the victim of a political assassination would elicit subjective responses – and this uncertainty would factor into any decisions about working with SCPE again.

Several industry participants say they can see another secondary deal getting done, perhaps as a staple. The large amount of dry powder in the secondaries market might be helpful in this respect. "There are all kinds of things investors will look at in Asia that in a different kind of market they might not look at," says one. "If the bank steps up with significant primary capital there is a chance of a deal getting done."

Others are unsure about the longer term prospects for the franchise as an independent GP. A number of PE firms with broad emerging markets coverage have seen spin-outs in different geographies – even in the absence of concerns about team stability and future fundraising, it can be difficult to hold things together. Much rests on the bank's ability to stay involved in the business for longer than it at one time might have envisioned, and whether the secondary portfolios perform well enough to convince the existing LPs to provide positive references to new investors considering primary commitments.

Risk factors

For some, the experience amounts to a cautionary tale. "It validates why we don't like backing captive GPs – this was supposed to be the exception because of the dynamic of the spin-out, but it still went wrong," one LP observes. Another investor describes the situation as "a classic case of why it's problematic working with banks," adding that whoever at the bank decided to terminate Stevens "really didn't think through the implications." These are not isolated viewpoints.

Standard Chartered appears to have suffered reputational damage as a result of the episode, and there could be additional financial costs as well. One question asked by several sources is why – as far as they are aware – no one within the bank has been held accountable for the decision. The answer may lie in the conflict that underpins many bank secondary transactions: the need to observe fiduciary responsibilities to LPs on one hand, and the need to act in the interests of shareholders on the other.

Standard Chartered had $122.2 billion in outstanding loans at the end of last year – more than 50 times the size of the balance sheet PE assets spun out through the secondary deals. Negotiating a private equity deal in the face of all manner of other, bigger ticket considerations is challenging, and it requires a keen grasp of who is making the decisions and why.

"You have to navigate through their decision trees and oftentimes these are not very transparent to outsiders. And it is important to find the decision makers," says HQ's Wu. "Any secondary deal requires a lot of knowledge of the seller, but this is especially true when dealing with a bank because the decision making process could just be a bit more complex."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.