The innovation game: China GPs play safe

China investors have abandoned their previous high-risk-high-return approach in favour of proven business models and profitability. Hotspots like autonomous driving, biotech, and SaaS are no exception

CowaRobot comes from the unfashionable backwaters of autonomous driving. The Chinese company has built up a solid business in the sanitation vehicle space through deals with the likes of Zoomlion Heavy Industry Science & Technology, one of the country's manufacturers of industrial vehicles. Orders are said to have exceeded CNY 500m (USD 69m) in 2022.

Earlier this year, CowaRobot closed a US dollar-denominated funding round at a valuation of about USD 1.5bn. Industry participants were surprised, and not just because the deal wasn't publicly announced. CowaRobot's rise juxtaposes broader challenges for the autonomous driving industry as robotaxi players struggle to live up to their former hype.

"CowaRobot originally focused on smart suitcases that can automatically follow their owners. Even when it transitioned to autonomous sanitation vehicles, they travelled at low speeds on fixed routes," said one investor with exposure to autonomous driving.

"The technology is more like sweeping robots than L4 or L5 self-driving technology [where there is a high level of autonomy or full autonomy] on high-speed roads. That they were able to secure funding at such a valuation, especially at this moment, is beyond my expectation."

This investor's portfolio includes WeRide, a leading robotaxi player that isn't expected to maintain its approximately USD 5bn valuation when it returns to market for new capital. WeRide's situation is not unique. It reflects a general frustration with the pace of commercialisation for robotaxis, which has prompted some companies to focus on lower-level autonomy that is already being rolled out.

"Since last year we have noticed a lot of Chinese L4 players attempting to enter the ADAS [advanced driver-assistance system, or L2 autonomy] space to generate revenue," said Skylar Liu, a director at Prosperity7 Ventures, a growth equity fund established by Saudi Arabian oil giant Saudi Aramco.

Liu was speaking to AVCJ in June, shortly after Prosperity7 made its first investment in China's intelligent driving technology industry. It backed Hyperview, an ADAS provider that works with a string of domestic carmakers – from SAIC Motor to BYD – and has achieved mass production on 30 models.

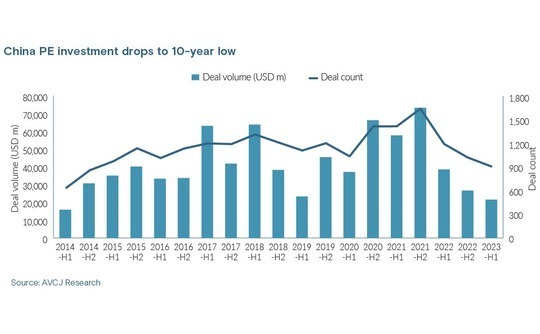

This reflects a broader mindset shift among Chinese private equity and venture capital investors that coincides with a sharp slowdown in deployment. Investment hit USD 21.6bn in the first half of 2023, the lowest six-month total in nearly 10 years, according to AVCJ Research. The speed of the drop-off is as notable as the size. Less than two years ago, in the second half of 2021, USD 73.2bn was put to work.

Investors in China are plagued by an assortment of headaches – economic uncertainty at global and local levels, geopolitical tensions with the US, and a difficult fundraising environment. When they do pull the trigger on a deal, they favour more proven business models. Risk appetite for cutting-edge innovation remains, but only when it is underpinned by sensible economics and sightlines to profitability.

Ramon Zeng, a general partner at DCM, a cross-border investor with significant China exposure, has noted the same trends playing out globally since the first half of 2022. "There's been a clear shift towards prioritising profitability over growth potential across all geographies and market levels. This has permeated public markets and private markets, encompassing various sectors," he said.

Healthcare in transition

Nevertheless, the phenomenon takes on a particular form in China, largely shaped by regulation. Biotech was a big beneficiary of the boom, attracting investment of USD 19bn between 2020 and 2022, up 5x on the prior three years. VCs were responsible for 60% of deal flow, drawn by the prospect of helping start-ups take advantage of stock exchange exemptions permitting IPOs by pre-revenue biotech companies.

Shanghai's Star Market, the most prominent onshore exit channel for high-growth start-ups, previously required candidates listing under this mechanism to have at least one asset in phase-two clinical trials and expect to achieve a market capitalisation of at least CNY 4bn. Now, though, informal guidelines have been issued that effectively mean companies must be profitable, according to two investors.

Casualties include Rongsheng Biotech, which terminated its Star Market IPO process this month, despite being approved for a listing last December. The move was triggered by exchange officials lodging four questions relating to high sales costs and the authenticity of revenue. In 2023 to date, six biotech start-ups have abandoned IPOs on the Star Market and 14 have walked away from A-share listings.

International markets have been unforgiving, with the XBI, which tracks US biotech stocks, down over 50% from its 2021 peak. According to EY, 55% of emerging biotech companies globally don't have enough cash to stay in business beyond two years, with 29% unlikely to last one year. In China, conditions are exacerbated by centralised drug procurement squeezing margins on new drug sales.

"Novel drug development is a luxury in the current environment, as capital markets won't give you unlimited funds to burn. I believe the capital market will remain challenging in the coming two years, making it difficult for new drug developers to raise funds," Wei Fu, founder and CEO of CBC Group, told AVCJ in April after his firm helped local player Hasten Biopharmaceutic buy a portfolio of mature drugs.

"As a rational investor, we must employ different strategies to navigate markets in different stages. We need to focus on companies with strong liquidities in the current market condition."

The Hasten deal demonstrates how the focus has shifted to companies that can generate cash flow. Sources familiar with the situation claim that CBC is looking to exit the novel drug development space and concentrate on later-stage investments, though Fu denied this.

The same sources said that Boyu Capital has already suspended novel drug investments. Indeed, the GP's most recent healthcare investment is a USD 660m buyout of Hong Kong-headquartered medical device manufacturer Quasar Medical. Fellow mid-market private equity firm CPE, meanwhile, is currently reconsidering a moratorium imposed on buyouts about three years ago.

CPE's recent activity in healthcare includes participating in a CNY 2bn round for Sangon Biotech, an outsourced R&D specialist that spun out from local genetic engineering specialist BBI Life Sciences. Shirley Lin, a partner at GL Capital, which co-led the deal with CPE, entered 2023 expecting the market to be sluggish with plenty of targets available at reasonable valuations.

"In fact, valuations have not undergone the expected adjustment to date as many investors show interest in late-stage and buyout healthcare deals," she said.

At the same time, the definition of late-stage appears to have evolved. When the Hong Kong Stock Exchange emerged as an offshore listing channel for pre-revenue biotech companies, investors considered pre-IPO deals as late-stage because of the promise of fast returns.

Then the bubble burst, and with companies trading below their IPO prices, the prospect of swift exits evaporated. Suddenly, late-stage was defined based on size and profitability, several investors observed.

Metrics re-examined

The emphasis on conventional late-stage deals is also a consequence of limited activity during the pandemic, one healthcare-focused GP added. Investors recognise that LPs want to see returns, and they are wary on taking on excessive risk by shooting for 5x when they know 2x would suffice. To some industry participants, it is a familiar scenario.

"In 2018, during China's economic deleveraging phase, many growth funds informed their LPs that their next funds would focus on buyouts. However, when the economy rebounded and several emerging sectors gained momentum, they quickly abandoned their buyout strategy," said Yichen Zhang, founder, chairman, and CEO of Trustar Capital.

While Zhang believes that the current shift towards buyouts will last longer than the previous cycle, the market downturn has not only impacted how managers think about investment stage. They are also reshaping their investment methodology.

For example, software-as-a-service (SaaS) lost its allure last year after a string of public market corrections wiped billions off the value of global industry leaders like Snowflake and Shopify. Many Chinese GPs pulled back, but CDH Investments was not among them.

The private equity firm recently led a CNY 200m Series B for 1Data, a robotic process automation (RPA) start-up that serves supply chain managers. Conviction around the asset was built on close analysis of previous behaviour, and a belief that the prevailing valuation metric of price-to-sales ratios – some start-ups raised capital at multiples as high as 50x – was unhelpful.

"Investors were solely focused on the growth rate, overlooking profitability. However, if a company's sales costs are too high, and these costs do not fall as the business scales up, there must be an inherent flaw in the business model," said Qizhi Guo, a senior partner in CDH's venture and growth capital unit, which made the 1Data investment. "The company may never achieve profitability."

Where once investors threw capital at SaaS companies as if they were consumer-internet start-ups and scale would conquer all, now there is a general recognition that sustainability means reaching a net profit margin of 15% by the time annual revenue crosses the CNY 200m threshold.

These sentiments were echoed by DCM's Zeng, who prioritises two metrics when assessing a start-up's long-term pricing power: sales efficiency and gross margin. While GPs always try to strike balance between growth and profitability, right now Zeng is advising certain portfolio companies to dial down growth in order to conserve cash flow.

"We place greater emphasis on cash flow, not only when selecting portfolios but also in portfolio management. Companies with positive cash flow are more likely to secure exit opportunities," he said. "We encourage our portfolios to strengthen their management and achieve self-sustainability at an earlier stage rather than pursuing rapid and uncontrolled scaling."

Opinion is divided as to whether the lessons learned in recent years will lead to a fundamental change in behaviour or just become footnotes in a history of repeated booms and busts.

One school of thought is that the traditional philosophical divide between US dollar funds and renminbi funds – the former are typically labelled as risk-tolerant whale-hunters, the latter as risk-wary conservatives with one eye on a near-term return – is narrowing.

At one Beijing-based venture capital firm, there have been just two investments so far this year. Both are "little giants" – niche operators that leverage strong innovative capacity to build significant market share. It represents a departure for a GP that has backed the likes of WeRide and LiDAR supplier Innovusion, but it was deemed necessary given the difficult US dollar fundraising environment.

For now, the emphasis is on deploying renminbi capital and this means adapting to the expectations of local investors. "The renminbi market is not capable of accommodating large-scale stories. Companies like Meituan, Tencent, and Alibaba needed the US dollar market to grow to their size," the manager said.

Little giant philosophy

Renminbi funds are targeting two main opportunity sets: spinouts from established companies and little giants. These are unlikely to deliver to achieve multi-billion-dollar valuations, but they have relatively predictable trajectories in smaller markets. A little giant might go public with a market capitalisation in the CNY 3bn-CNY 20bn range, the manager added.

There have been instances of little giants outgrowing their potential on the back of favourable policy support. Hikvision has become the dominant player in China's video surveillance space with a market capitalisation of CNY 300bn, eclipsing the four "AI dragons" – SenseTime, Yitu Technology, Cloudwalk, and Megvii Technology – that received substantial funding from US dollar investors.

The company was patient, spending little as the AI dragons pushed ahead with face recognition solutions, and then acting decisively when the technology became mainstream. Once a buyer from SenseTime, Hikvision developed its own algorithms to complement its existing hardware. This end-to-end offering enabled the little giant to overcome the would-be whales.

"What happened to Hikvision is very similar to what is happening in autonomous driving. Car makers are accumulating data, so there's no need to build autonomous driving algorithms," said one venture capital investor who has backed a leading local electric vehicle manufacturer.

"Those algorithms will become less scarce technology, and then the car makers can leverage their data reserves to launch their own autonomous driving services. The current L4 developers – it doesn't matter whether it's Pony.ai or WeRide – will end up going nowhere."

This would appear to vindicate the notion of backing a stable business that offers immediate cash flow over a less proven but more cutting-edge technology. However, the newfound discipline doesn't hold true across all industries, as ably demonstrated by the excitement around the transformative potential of generative artificial intelligence (AI).

Dozens of academics and entrepreneurs are looking to build large language models (LLMs) given the absence – for now – of a Chinese equivalent to US-based OpenAI. Interestingly, renminbi funds are leading the way. According to local financial advisor Xiaofanzhuo, 70 LLM start-ups raised capital in the first eight months of 2023. The split was 58-12 in favour of renminbi funds.

There are various explanations for this, from US dollar investors avoiding politically sensitive areas to LLMs being a good fit for the little giant profile. That said, these deals are happening despite the substantial costs and risk involved, especially as China's technology giants develop their own LLMs.

"The academic papers were out there, but no one was sure how to productise the foundation model. OpenAI demonstrated it was possible and others want to follow," said Gan, founding managing partner of Ince Capital Partners, who expects to make a couple of investments in the space.

"But yes, they need a lot of money, a lot of data, a lot of computing power, and a lot of engineers to build the infrastructure."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.