Vietnam middle market: Room for maneuver

There is a perceived sweet spot in Vietnam where check sizes are too big for local GPs and too small for pan-regionals. Taking advantage means addressing structural nuances and strategic competition

VI Group's exit activity in 2020 followed a familiar pattern. Six months of relative inactivity as COVID-19-related economic uncertainty made buyers reluctant to engage; and then three transactions in the second half of the year. "People were more accepting of using locally based advisors and doing remote due diligence," observes David Do, a managing director with the Vietnam-based firm.

There is no question that investors remain bullish on the Vietnam growth story; if anything, it was augmented by the country's early success in controlling the spread of the pandemic. And VI Group's exits reflect the nature of financial and strategic interest in the country: one asset went to a regional private equity firm and the other two were picked up by Japanese and Korean corporates.

VI Group closed its most recent fund at $252 million, which would typically equate to a $10-30 million sweet spot. Mekong Capital entered similar territory earlier this year, having raised $246 million for its fourth flagship vehicle. VinaCapital operates a variety of funds and seeks to be a bit more flexible, with a range of $20-50 million, while PENM Partners is a bit smaller.

Assuming the large-cap global and pan-regional players are reluctant to write checks of less than $150 million, this leaves a gap in the market that various middle-market managers are keen to populate – primarily targeting founder-owners directly, but with the odd secondary as well.

"The ecosystem isn't fully developed in Vietnam. We've yet to see local private equity firms scale the way managers in other markets have scaled. They are focused on nurturing businesses from a relatively early stage, while larger funds that want to access Vietnam aren't going to the grassroots," says Bert Kwan, a managing partner at BDA Capital Partners. "There's a gap and we want to fill it."

The exit angle

BDA Capital is a new arrival in Vietnam and currently working on a deal-by-deal basis. Kwan joined the firm last year from Northstar Group, a Southeast Asia-focused player looking to fill the same gap. Before Northstar, he pursued a similar remit at Standard Chartered Private Equity, now known as Affirma Capital. Southeast Asia-based Creador and Navis Capital Partners and Chinese GP CDH Investments are the other names routinely mentioned, but various others are considering Vietnam.

They will likely run into plenty of strategics chasing the same deals, with Thailand joining Korea and Japan as the most prolific foreign actors. This competitive tension is welcomed by LPs in a market where exits have been patchy. According to AVCJ Research, there has been an average of 10 per year over the past decade, with trade sales accounting for more than two-thirds. During this period, the annual total reached as high as 20 and as low as five.

"We expect to get a 2x net return from Vietnam managers with mid-to-high teens IRR," says Koon Kiat Poh, a principal at Axiom Asia Private Capital. "Companies are often quite small when managers make the initial investment, so it can take time to get them to a size suitable for acquisition or a public listing. The upside is you can get an outlier and generate an outsized return."

This view is echoed by Sam Robinson, a managing partner at North-East Private Equity Asia, who also has country-level GP exposure. He believes the real problem is a lack of high-quality assets, which means managers are more inclined to hold on to something good when they find it. However, Robinson notes that the sample size is small, the intermediary infrastructure is improving, and local managers have started to turn accumulated experience into better performance.

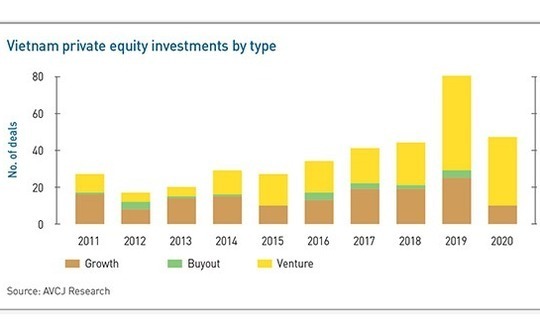

There is certainly more investment activity. Headline dollar values are deceptive because a single sizeable deal can seemingly turn a fallow year into a flourishing one. But the average number of transactions between 2016 and 2020 was 49, twice the total for the preceding five-year period. Venture capital and technology-related growth investments are the major drivers.

"The main problem in Vietnam remains exits and DPI [distributions to paid-in]. We can offer a solution to managers," says Paul Robine, founder and CEO of TR. "We want to invest in established leaders, help them scale, and potentially sell to an international or pan-Asian fund because by that point the deal size will be big enough for them."

Nuanced secondaries

There is an established trend in several other markets in Asia of businesses being passed from financial sponsor to financial sponsor as they grow in scale and their needs evolve. Both Japan and Australia have seen multiple instances of smaller country GPs selling to larger local peers before a pan-regional player arrives to take the asset to the next level.

Vietnam offers a variation on this theme. First, there is a tendency for private equity firms to gravitate towards counterparties of size and repute. KKR embarked on its second investment in a Masan Group business in 2017, taking out PENM in the process. VinaCapital, Mekong, Goldman Sachs and TPG Capital have all backed the parent or a subsidiary at different times.

Vingroup is another frequent PE collaborator. KKR and Temasek Holdings are investors in property developer Vinhome, GIC owns a piece of hospital operator Vinmec, and Warburg Pincus previously backed shopping mall developer Vincom Retail. These deals don't necessarily see private equity exit directly to private equity, but they offer a snapshot of a market in which familiarity brings comfort.

Second, where there is an unbroken chain of sales between financial sponsors, they seldom involve controlling stakes. Mekong paid $3.5 million for 35% of mobile phone retailer Mobile World in 2007 and helped the business scale aggressively. China's CDH Investments arrived in 2013, taking a 19.88% interest for $20 million. Most of the shares came from the founders but Mekong made a partial exit.

Mobile World listed in 2014 at a valuation of $200 million, facilitating pre-IPO partial exits for both GPs. Mekong sold the last of its shares in 2018 to Creador in what represented the Southeast Asia and India-focused manager's first investment in Vietnam. Mobile World now has more than 4,000 stores across six concepts and a market capitalization of $3 billion.

Restaurant operator Golden Gate arguably makes for a purer example because there was no IPO in the middle. Mekong's original investment in 2008 was sub-$5 million. Six years later, the business had grown sixfold and Standard Chartered Private Equity – now known as Affirma Capital – bought a 45% stake for $35 million. In 2019, CDH acquired Affirma's position for nearly $100 million, according to a source close to the situation.

AVCJ Research's records do track an increase in secondary sales in recent years, albeit from a low base. Eight were announced between 2016 and 2020 compared to three in the five years before that.

There have been instances of local GPs selling directly to global players, but they are rare. In 2017, Mekong and Denmark's Maj Invest exited their positions in Vietnam Australia International School to TPG. The deal made sense only because the company founder sold some shares as well, enabling TPG to write a meaningful equity check and secure control.

Competitive dynamics

Exiting alongside the founder-owner is the product of careful negotiation, with price, age, and the number of parties involved – some companies have multiple founders with different investment horizons – all potential motivating factors. If a controlling stake is available, that would likely attract more interest from a range of strategic buyers, but some are willing to settle for a minority interest if they see value in the target.

"If the founder is willing to sell as well, it's more likely to go to a strategic," says Chris Freund, founder and partner of Mekong. "However, the Japanese – and maybe the Koreans – can be happy with minority stakes. We have a Japanese strategic partner and that's their philosophy: start small, think 100 years ahead, don't risk too much money upfront, get to know each other, and build from there."

VI Group sells more frequently to strategics than private equity. Do claims that private equity players generally don't pay as much, in part because there is limited scope for leveraged financing, and they want substantial downside protection in the form of earnouts for the founder. Nevertheless, the two buyer groups are not necessarily equally aggressive in the same sectors.

The asset VI Group sold to private equity last year was Transcendental Human Resources, an online recruitment platform also known as Sieu Viet. It went to Affirma. Meanwhile, the Japanese strategic player acquired a logistics business. It represents the second time VI Group has sold a logistics asset to a buyer from that country.

Logistics, retail, healthcare, and education are identified as the sectors with sufficient scale to enable a large-cap private equity firm to write a $150 million check. Japanese, Korean or Thai strategics could pop up as bidders in any of these areas, but they are also interested in assets that complement their core business operations. Japan and Korea, for example, are the largest sources of foreign direct investment in Vietnam due to longstanding commodities trading and outsourced manufacturing.

"As a financial investor, we may not be keen to invest in a Vietnamese manufacturing business that is growing at less than 20% annually. However, strategic players might see significant synergistic value in such a business. In these situations, we would bring in our portfolio company and evaluate the bolt-on opportunities," says Thuy Dropsey, co-head of ASEAN at Affirma.

For example, Affirma previously owned a Korean packaging business and made introductions to Vietnam-based companies with large customer bases with a view to driving volume growth. This led to M&A and the Korean business, which had more advanced technical capabilities than its Vietnamese peers, ended up investing more capital to upgrade the production lines.

Travel restrictions have underlined the importance of having a local presence. Paul DiGiacomo, a managing partner at M&A advisory firm BDA Partners, which has a sizeable office in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), observes that the uptick in exit activity for VI Group in the second half of 2020 reflects a broader market trend. Those with the ability to transact within COVID-19 parameters were better positioned to move quickly once processes restarted.

"Large Thai corporates, Korean conglomerates, and Japanese trading houses have been in the market for a long time. They are comfortable with it, and they have teams on the ground," he says. "They can tick the boxes in terms of touch and feel and kicking the tires with relatively senior people. That's not the same as someone who has a sales office and people with no experience assessing assets."

Local knowledge

Opinion is divided within the private equity community as to the level of difficulty investing in Vietnam versus other countries in Southeast Asia. Lanyi of CDH maintains that it is one of the easiest places to do business and the size of the opportunity set – rapid economic growth, a large and relatively young population, an emerging consumer class, supply chain relocation from China – is attracting new participants.

Others point to the differences in system of government and nature of corporate ownership that make Vietnam more like China than Indonesia. Most middle-market GPs in Southeast Asia target no more than three or four of the 10 ASEAN markets. It is an open question as to how quickly those that aren't established in Vietnam will seek a toehold there. David Ireland, a senior partner at Navis, claims that he has "seen funds with Vietnam in their mandate but who don't really put time into it."

The consensus view is that, even absent COVID-19, an on-the-ground presence is invaluable. The local talent pool has deepened. Ten years ago, most recruits came from accounting or securities firms and had little direct investment experience or the soft skills required when dealing with entrepreneurs. The situation has improved, in part because investment professionals who cut their teeth with local managers are moving through the ecosystem, but hiring is still hard.

One investment professional with a middle-market firm notes there is still a tendency to staff HCMC offices with junior executives – it's difficult to find anyone at director level or above – and run deals out of regional bases. At the same time, private equity firms aren't the only ones looking for talent. Strategic players from Japan and Korea want to recruit investment professionals, with Korea's SK Group said to have accumulated significant headcount across Hanoi and HCMC.

"In the past, Indonesia was the more attractive market for regional private equity players, but that is changing. They are now trying to build local teams in Vietnam. The fly-in, fly-out model is hard to do because they would get the intermediated deals," says Axiom's Poh. "Exits haven't been as fast as in other markets like China, but there is more optimism around returns, especially with supply chains starting to move from China to Vietnam. The macro trends for growth remain strong."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.