Southeast Asia macro: Encouraging minefield

Southeast Asia benefits from an enviable macro outlook versus other markets, and investment in the region is set to recover relatively quickly. But is that enough?

In the memories of most investors, Southeast Asia has always been a fast-growing playing field for opportunism, experimentation, and creative risk-taking. That interpretation is not going away, but it is starting to be layered onto an older, and perhaps more relevant, characterization.

In a wider historical context, including the proxy wars and economic earthquakes of a grueling, half-century decolonization period, the region's core identity has been that of the hardy survivor, eking out gains in the face of macro pressures that were beyond its control. To a large degree, the global COVID-19 downturn is bringing that perspective back to the fore both at the level of the overall market and individual investments.

"If you look at the conversation last year, the underlying theme was globalization and supply chain efficiency. That dated back to the US-China trade issues, and COVID-19 has accelerated it. Now, the focus is resilience," says Luke Pais, private equity and M&A leader for ASEAN at EY. "What's the resilience of my product, market, supply chain, and manufacturing? It's about having resilience in operations both as far as top-line and operating structure are concerned."

This view is contributing to a sense that Southeast Asia's defining economic trajectory will not be significantly deterred in the decades to come. The region's aspirational population of 650 million will continue to represent favorable demographics for investors, as will a number of sweeping themes related to infrastructural modernization and the gradual diversification of the hemisphere's China-dominated industrial capacity.

Taking a hit

In the immediate term, however, Southeast Asia's economy is expected to fare worse than it did during the Asian financial crisis of 1997, with recessions in countries previously viewed as enjoying unshakable parabolic growth. According to the IMF, GDP will shrink 2% this year. As the most globally integrated market, Singapore will be the hardest hit, sliding 3.5%. Only Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines are expected to chart growth – 2.7%, 0.5% and 0.6%, respectively.

Still, this is significantly better than most of the developing world. While China is projected to grow 1%, Russia, Latin America, the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa are tipped to tumble 6.6%, 9.4%, 4.7%, and 3.2%, respectively.

Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis, attributes the outlook to Southeast Asia's monetary policy, which is seen as more independent than other developing regions due to greater foreign exchange reserves and more robust liquidity assistance from the likes of the IMF. "These countries are resilient and they are recovering faster than we thought," she says. "I still hold the view that notwithstanding COVID-19 – and of course it's all relative – Southeast Asia will be a winner."

For private equity, the main concern is the march of social mobility, and by extension, middle-class consumerism. Many GPs have begun framing their planning scenarios in pre-vaccine and post-vaccine terms, contemplating various bounce-back scenarios across the next 1-2 years. The biggest landmines here are the rising levels of unemployment and the threat that they will not necessarily reverse with the advent of a vaccine.

The recovery outlook for the jobs market is clouded by the fact that so much of it in Southeast Asia is off the books. Many countries in the region are said to count up to 50% of the workforce in the informal sector, with the notable exception of Singapore. These groups are not easily targeted by government stimulus packages and will have access to few resources when the time is right to re-launch their hibernating cottage industries.

Regional investors see a way forward in leapfrogging technology uptake and the idea that the traditional labor force can re-skill and up-skill to fill new-economy jobs. Northstar Group, an early investor in Gojek, notes that the Indonesia-based ride-hailing and multi-service app has significantly increased the earning power of motorcycle taxi drivers while also connecting new customers to food and beverage merchants.

"We view most of the COVID-19 induced unemployment as temporary rather than structural. That said, certain sectors – such as tourism and to some extent business travel – are going to recover very slowly," says Tan Choon Hong, co-CIO at Northstar. "We see digitization creating more growth and greater opportunities across the region with the rise of mobile connectivity driving productivity gains and job creation."

Nevertheless, tech tailwinds have done little to shore up the other major pillars of the Southeast Asia investment narrative.

Building capacity

Infrastructure development, for example, is a major unknown in the current climate, with China's Belt & Road agenda seen as grinding to a halt. Most of the infrastructure investment in the region so far this year has been in soft categories, including healthcare. But this has come primarily from non-Chinese players, raising questions as to whether the country's state banks still have the capital and risk tolerance for large ASEAN projects that might not pay off.

Southeast Asia's complex geographies and patchy progress in urbanization make any slowdown in infrastructure development a serious concern for broader economic momentum. However, the idea that COVID-19 is putting mega projects on ice could be a blessing in disguise for countries looking to minimize their debt burden with Belt & Road policy banks. There is a sense that some transportation projects – now fortuitously stalled – could become redundant in a post-virus society that moves in unexpected new patterns.

There are also mixed signals in the global supply chain story that pegs Southeast Asia as the biggest beneficiary of US-China trade tensions. Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand are still expected to attract the most investment in manufacturing, which should drive meaningful opportunity for private equity. But it remains questionable whether this activity can achieve sufficient scope to support a faster recovery in terms of wages and spending power at the consumer level.

"The biggest problem is capacity. There's just not enough manufacturing capacity in Southeast Asia to take all the investment that might want to leave China," Gregory Poling, a senior fellow focused on Southeast Asia at the Center for Strategic & International Studies in the US. "At some point, you hit a bottleneck, where you can't set up factories in Vietnam quickly enough to leave China if you wanted to."

Issues around international trade and supply chain flows also call into question the outlook for multi-lateral cooperation post-virus both within ASEAN and with external spheres of influence. Within the region, the freezing of travel is perhaps the biggest variable, with Singapore Airlines currently operating at about 7% capacity.

Travel bubbles are expected to form between Singapore, Malaysia, Korea and Australia, although timing is unclear. Indonesia and the Philippines, representing more than half the population of the region, are at risk of being cut off from this group. This effect would be partially mitigated by the island nations' relative lack of cross-border economic integration with their continental counterparts. If the segregation persists, it will be all the more to the advantage of investors with existing teams and partners in those geographies.

Globally, the decoupling and isolationism that has come with the coronavirus-trade war nexus has kept ASEAN on the diplomatic sidelines. There is little expectation that the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership will result in meaningful changes to tariff regimes. However, countries particularly hurt by a lack of tourism, such as Thailand, could attempt to align themselves with the Trans-Pacific Partnership in a ploy to mix up their stagnation.

"The big picture is that both China and the US are reinforcing Southeast Asia's worst assumptions about them. At the political level in a lot of Southeast Asia, that's going to lead to countries seeking greater diversity in the form of outreach to Japan, Australia, and India, although they can't fill the void," Poling says. "Part of it will be looking to international institutions, especially ASEAN. It will be country-by-country, but when you step back and look at the whole landscape, you're likely to see more splintering of influence in the region."

In investment terms, most expectations revolve around a growing Chinese presence, especially in the region's technology ecosystems. This was the theme of a recent report by Singapore-based Golden Gate Ventures and Japan's Daiwa Capital Markets that tracked China's growing influence over Southeast Asian start-ups not only in financial support but also conceptual guidance on business modeling and data policy.

The China factor is soaking in at the GP level as well. Golden Gate sends one of its founding partners, Jeffrey Paine, to China four times a year. The firm also stages periodic events in the country such as an ASEAN-China summit recently co-organized with ZhenFund, Last year, it recruited Freddy Shen, a Chinese national formerly of Bain Capital, to add a local perspective on China platform plays to consumer tech analysis.

Vinnie Lauria, a co-founder at Golden Gate who advises Tsinghua University's executive MBA program, notes that while acquisitions and later-stage deals attract significant Chinese investment in Southeast Asia, it has not been possible to fully tap the region's promise without local deal sourcing networks. AVCJ asked whether Chinese VCs could eventually set up shop in Southeast Asia with separate versions of themselves in the way US players such as Sequoia Capital and Matrix Partners created China-based entities in the early 2000s.

"So far, I've known of Chinese VCs hiring junior investment teams on the ground in Singapore or Indonesia, but not a senior partner level person – and you need that to source great deals and have a voice at the investment committee," Lauria says. "I've also seen with three funds now that require any local hires to speak Mandarin, which makes it hard to get a really senior local person."

Post-COVID prospects

The prospects for locally-driven investment in the foreseeable future will vary widely across Southeast Asia depending on success dealing with COVID-19. The general consensus is that Vietnam is in a class by itself. The country has limited infections to four cases per one million people, and no deaths have been associated with the virus.

Thailand and Malaysia are regarded as slower to react but not devastatingly so. Their reliance on tourism is a danger. The Philippines and Indonesia are usually framed as the most likely losers due to a combination of poor government response, lack of connection with regional supply chain and infrastructure themes, and the possibility of being excluded from travel bubbles.

Singapore, meanwhile, seems to have captured the spirit of the wider region with its heroic, but ultimately questionable, government spending. The city-state has announced three stimulus packages worth $42 billion, or 12% of national GDP, to keep the economy afloat. For now, though, it remains unclear how much this will help. The government recently confirmed GDP contracted 12.6% in the second quarter.

For private equity, the hope is that after a period of a few months, government programs across the region will have run dry, leaving small to medium-sized enterprises (SME) starved of financial support and more amenable to M&A or venture investment. This scenario is widely expected to play out, but it may not do so on a scale that is meaningful to national economies or even the investment industry at large.

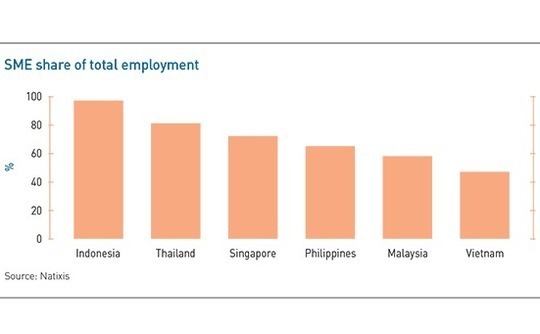

The problem is that most of the government relief in Southeast Asia to date has come in the form of social safety nets for low-income individuals or bailouts for state-owned enterprises. Natixis notes, however, that SMEs are often a disproportionately large slice of the economy in Southeast Asian countries. They account for 97% of jobs in Indonesia and 81% in Thailand.

By comparison, 68% of jobs in Australia are in SMEs. Targeted government support for SMEs in the country comes to 5.2% of GDP. In Singapore, 72% of employment is in SMEs, but these businesses receive only 0.8% of targeted government support.

"In Southeast Asia, the stimulus packages have not been designed in the right way to protect the consumer, but that's the backbone of their growth story," says Natixis' Garcia-Herrero. "If you support SMEs, you are literally supporting the people working for those SMEs. If consumers don't get paid because companies are no longer running, it goes to the heart of the consumption-driven growth model we've been seeing in Southeast Asia for a long time."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.