Japan carve-outs: Profit from the core

Private equity firms hoping for a coronavirus-driven uptick on Japanese corporate carve-outs must be patient – and come armed with considered value creation plans when the time arrives

Baring Private Equity Asia never expected to own Pioneer Corporation. Its relationship with the Japanese conglomerate began to deepen around 2012 when a couple of divisions were identified as prime candidates for carve-outs. Baring lost out to KKR on Pioneer's DJ equipment business in 2014 and a move to acquire its audio-video operation fell through later the same year.

But the two teams remained in contact, discussing various ways in which the GP might help Pioneer address its worsening financial position. The Japanese company's ability to capitalize on emerging technologies – it rose to prominence in the 1980s with laser discs – appeared to have vanished with lackluster forays into car navigation systems and plasma displays. It was losing money and debt was piling up.

Two years ago, when Pioneer's banks decided to pull their support, Baring came in with a JPY102 billion ($947 million) revitalization plan. An immediate cash injection stabilized the company's balance sheet and it was followed by a privatization. Now under Baring's ownership, Pioneer is focusing on mobility solutions – such as autonomous driving technology – and related services, rather than manufacturing.

"There are some existential risks to the business: it's in automotive and technology, and there is a lot of industry change," says Shane Predeek, a managing director at Baring. "We believe that Pioneer failed in its management of capital allocation, so our number one focus was identifying the areas we should and shouldn't be investing in. We have also put the right people in place. The company was distressed but its problems are representative of a lot of the problems in corporate Japan."

Helping the country's conglomerates address these problems – chiefly by carving out non-core assets – is a longstanding private equity strategy. More traction has come in recent years as increased emphasis is placed on corporate governance, transparency, and return on equity (ROE). Pushed by policies intended to improve accountability and pulled by the need to remain competitive in crowded global markets, corporate Japan is beginning to recognize that profitability is more important than scale.

The big question is whether financial stress arising from the coronavirus outbreak will encourage more divestments. And, by extension, whether corporates will be more open to PE overtures. The short answer is not yet. Investors believe they must wait years rather than months for more assets to become available, but there will be rich pickings when they do. Moreover, there's an argument to be made that Japan could benefit as much as private equity.

"The original motivating factors had nothing to do with COVID-19, it was about corporates being more efficient and effective in managing their businesses. And they realize that private equity can work with them on this," says Koichi Tamura, a senior partner at EY. "However, COVID-19 has accelerated the mindset about the need for change. It will probably be our generation's last chance to reshape Japan and make it relevant in global markets."

Gradual rise

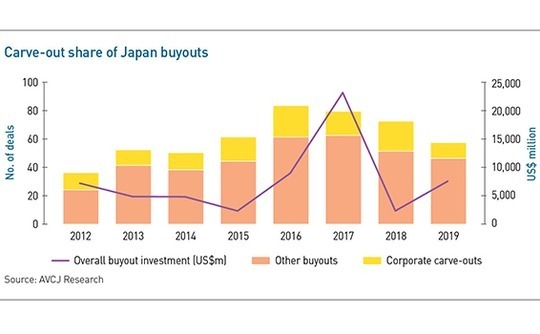

Over the past five years, the annual average number of M&A deals involving Japanese sellers of Japan-based assets exceeds 450, according to AVCJ Research. The most prolific buyers are other local corporates; private equity penetration is minimal. The average number of PE buyouts during the same period was 70, of which 17 were carve-outs. Prior to 2015, the carve-out total barely exceeded single digits; it rose thereafter, although 2019 reverted to this historical norm.

The increase coincided with a surge in overall buyout activity in Japan – there were twice as many deals in 2016 as in 2012 – but it was mainly driven by succession situations. Carve-outs began to attract more attention by virtue of their size. Eight of Japan's 10 largest buyouts on record have closed within the past six years, and five of them are carve-outs, including the top three.

Hitachi is the traditional poster child for Japanese corporate carve-outs, promising bold structural reforms in 2009 and going on to divest a string of non-core assets. The job is far from complete, with a goal to reduce the number of group companies from 800 to 500 by 2022. This is part of an effort to reconfigure Hitachi for the digital age, emphasizing artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics. Others have similar ambitions, including NEC, Fujitsu, and Pioneer.

"Fujitsu has said its strategy is software, not hardware. It used to be hardware came before software – software was viewed as a service and you couldn't charge for it. Now the situation has changed. Hardware has become more commoditized, so it's harder to differentiate," says Hiroshi Hayakawa, a partner at Advantage Partners. "That's a fairly typical way of thinking, but every company has its own strategy."

At the same time, internal resistance to divestment can be deep-rooted. The senior management teams of these subsidiaries are often populated by long-serving group executives who are winding down their careers in low-growth mode. They may not appreciate the arrival of a PE investor with a change agenda.

"In many companies, the retirement age is 55 and if you reach a certain level of seniority you can work for another five years. Then they go to a subsidiary from 60-65 and if they are president level, they might be able to carry on to 70," says Jun Tsusaka, founding partner of NSSK. "It is part of Japan's retirement infrastructure. They have a few more years of getting paid for doing nothing, and if they are the CEO, they get driven around in a limousine with a business expense account."

Politics can be a disincentive to act, especially if the subsidiary is not large – so a sale wouldn't make much difference to the parent's balance sheet – and the recalcitrant executive wields considerable power. Paul Ford, a partner at KPMG, recalls one divestment being shelved for three years until the CEO of the subsidiary had retired. However, several GPs note that they usually find management teams are motivated by the notion of working with a PE sponsor because it promises more opportunities for growth. Often, the parent addresses dissension in the ranks before bringing a business to market.

Divestment decisions

There are several reasons why a division would be considered non-core. Typically, its addressable market or growth prospects might be too small to justify additional investment from the parent or there are internal problems that are difficult or costly to rectify. Tsusaka adds two more contemporary factors: activist investors pressuring the parent to divest assets; and companies facing substantial costs as they recalibrate supply chains to reduce reliance on China. He expects the latter to shake loose a host of mid-size subsidiaries that corporates previously weren't motivated to sell.

Whether COVID-19 helps push these deals along is another matter. The Japanese government announced a JPY117 trillion stimulus package last month and is said to be considering an additional injection of JPY100 trillion, which means banks are likely to support existing borrowers. "A bunch of low-interest loans will keep companies afloat, so maybe they won't have much incentive to divest," observes Tsuyoshi Imai, a partner at Ropes & Gray.

If conglomerates can wait out the instability in expectation that valuations revert to previous levels, they will do so. As such, few PE investors expect 2020 to be a bumper year. A few distressed sellers aside, more opportunities will emerge in 2021 and beyond as financial pressure intensifies the longer-term drivers of carve-out activity. Some corporates will divest according to strategic plans; others will be more opportunistic.

"In the short term, we don't think carve-outs will increase significantly because of COVID-19, but we expect to see over-indebted companies selling businesses," says Hiroyuki Otsuka, a managing director in The Carlyle Group's Japan buyout team. "A lot of companies in Japan have been impacted by COVID-19 and they have to fix their core businesses. Stronger companies will become stronger, and weaker companies will become weaker. This will lead to more industry M&A activity and consolidation, and carve-outs will increase because of this activity."

All the larger GPs maintain consistent touchpoints with major conglomerates, much like Baring did with Pioneer. Predeek explains that you "have to be in front of a large corporate once a quarter for years before they put you on the list," although an eight-year lead-in is unusual. Two-and-a-half years is the longest Advantage has spent on an opportunity, and processes have generally speeded up as corporates talk to the same private equity firms time and again.

Sifting through the holdings of hundreds of mid-cap corporates, investors rely on top-down industry research as well as direct or intermediated inbound inquiries. For the likes of Hitachi or Fujitsu, approaches can be more structured. They will look at what is potentially available and apply a filter based on the parent's strategic direction to come up with a list of realistic targets. Then it is a case of keeping up a regular dialogue, suggesting what could be done to realize value in different ways.

Engagement is usually initiated at the parent company level, but there might be concurrent exchanges with stakeholders ranging from banks – to find out what the corporate is thinking – to the management of the target division. It is a labor-intensive and delicate process. "We don't have regular contact with corporate planning departments, but access is not that difficult," says Gregory Hara, CEO of J-Star. "Getting access to the management of the subsidiary is harder, but if they come to us and discuss a management buyout, the success rate is much higher."

J-Star operates in the lower middle-market and expects to see more carve-outs in its succession-dominated deal flow as divestments proliferate. Smaller deals are less likely to be widely intermediated processes. Richard Folsom, a representative partner at Advantage, observes that full auctions are not always in a parent's best interests. Sometimes, getting a sensitive deal done quickly and quietly is more important than pursuing a slightly higher valuation.

The playbook

Advantage completed its first carve-out 20 years ago, but Folsom believes the basic playbook is largely unchanged. The first challenge is ensuring an orderly transition from the parent, putting in place internal infrastructure that is missing – human resources, financing, and IT functions are often managed centrally – and reaching agreements with the parent on services that will roll over, such as intellectual property rights and perhaps employee health insurance.

According to KPMG's Ford, Japanese companies are traditionally good at building long-term relationships with customers and suppliers and achieving financial stability, but less effective at optimizing operations for profitability, cash flow generation, and agility. An immediate priority for PE investors is establishing systems that offer visibility into the key commercial drivers of a business, so that working capital and cash conversion cycles can be improved.

"You need to make changes to the operating model – how you are organized, how you make decisions – and establish clear KPIs [key performance indicators] so you can control the business," adds Jim Verbeeten, a Tokyo-based partner at Bain & Company. "It's also important to make sure early on that you are aligned with management on strategy. Especially with carve-outs, you are acquiring a corporate bureaucracy."

People management is crucial to achieving the transformation objectives that come with carve-outs, whether they involve domestic consolidation, international expansion, repositioning the brand, or recalibrating product and service offerings. Private equity investors must be far more collaborative with incumbent management teams in Japan compared to carve-outs in Western markets. They may want to empower change agents in middle management and supplement them with external resources, but changes in corporate culture are rooted in evolution rather than revolution.

Baring works to the assumption that the existing executives are not able to run a division once it separates from the parent, with Predeek arguing that there is more scope for improvement in Japanese companies by adding c-suite resources than any other market in Asia. Other investors set strict deadlines for reforming management mindsets. Carlyle's Otsuka asserts that if nothing changes within 6-12 months, it never will. Employees must recognize that PE is taking the business on a new track or they will become indifferent and retain old habits.

"This is the biggest issue we face when doing corporate carve-outs, especially involving larger Japanese conglomerates," adds an executive with a mid-cap local PE firm. "We need to change the culture and enhance governance. But many of these people are more receptive than proactive – they wait for instructions rather than take the initiative. We call it the large corporate disease."

Fatal missteps

Act quickly and it is possible to switch out management and minimize the damage. Asked where carve-outs are most likely to go wrong, industry participants point to more fundamental misjudgments of the market opportunity or the scope for transformation.

Several advisors observe that private equity firms are comfortable with bottom-line value creation – figuring out more efficient operational and financial metrics – but find it harder to address certain top-line issues. They can focus on growth initiatives that the parent didn't regard as worthwhile in the context of its overall business, such as investing in product development or targeting consolidation through M&A. However, they struggle to fix problems the corporate couldn't resolve.

"Most companies come with an issue, an operational, product or service deficiency that impacts competitiveness," says Tatsuo Kawasaki, a partner at Unison Capital. "We look for bottlenecks, situations where if we were to remove the parent, the rules of the game would change."

Unison found this in Ken Depot Corporation, a building materials distributor it acquired from Lixil Corporation in 2015 and sold last year. Despite strong underlying business growth, the company was losing money. Lixil was reluctant to address the problem because its core business involved selling building materials to wholesalers, and Ken Depot was essentially competing with them. Unison led a turnaround by redistributing resources to focus on more profitable areas.

Advantage faced a different kind of complexity when it acquired Sanyo Electric's digital camera division from Panasonic in 2012, paying $1 million in equity due to accompanying pension and trade liabilities. Revenue had nearly halved in the preceding years as mass-market digital cameras were supplanted by smart phones; neither parent nor private equity owner could do anything about this. Instead, Sanyo took a different path, concentrating on more specialized and profitable imaging applications.

The GP was operating in an area that presented an element of existential risk and got comfortable with this by calculating the bottom of the market, the growth potential, and the optimal entry valuation. Get these assessments wrong and the math underpinning a deal no longer makes sense. This can be particularly acute with legacy manufacturing businesses – much of what the software-focused conglomerates are trying to divest might qualify – where the goal is to rationalize oversupply.

"If the rationalization needs to go further than expected, there's not much you can do about that. You could end up with 100% capacity and demand is only 60%," adds Folsom. "We have seen examples in Japan of investors misunderstanding where the opportunity lies."

The hand of time

Private equity firms engaged in comprehensive value creation work can also get wrong-footed by macroeconomic shocks, the effects of which are compounded by leverage. A couple of KKR's Japan carve-outs are characterized by the pursuit of scale. Panasonic Healthcare has more than doubled in size over the past seven years through M&A, notably the purchase of Bayer's diabetes care unit. KKR repeated the trick with auto components supplier Calsonic, paying JPY4.5 billion for the asset and then adding on a division of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles for EUR6.2 billion ($7.1 billion) a year later.

The merger created Marelli, the world's seventh-largest independent auto components supplier, but performance has suffered due to issues beyond the company's control. First, Nissan – Calsonic's largest customer – has struggled with declining sales in recent years, then COVID-19 cut into the automotive entire automotive industry. This cranked up the pressure on a business that is already carrying 6x leverage and requires additional investment to stay relevant in a market where connectivity is becoming as important as powertrains, according to industry sources.

KKR may yet turn Marelli into a winner – the investment is currently marked at 0.5x, say investors, who claim to be most worried by the leverage – but it needs time. While complexity is company specific, larger operations tend to be more global, active across multiple domains, and have additional layers of management. As a result, it takes longer to alter course.

"The bigger the organization, the more time you need to allow for change," says Baring's Predeek. "If you don't have the proper infrastructure, it could take a year to build it. With a smaller company, you might be able to reset the strategy, get new people in place and change the mindset of existing management in six months. For a company like Pioneer, that could take 12 months."

The costs of miscalculation can be dear. Several global and pan-regional GPs have expanded their presence in Japan with a view to participating in the carve-out story. Investors that deliver positive outcomes from these situations will win the confidence of local conglomerates and may find that more opportunities follow. Those that do not may take years to reclaim their place on the list of favored partners.

"Sellers, especially traditional Japanese conglomerates, are always worried about the credibility of the buyers," says Carlyle's Otsuka. "They look at how you have created value in the past, which means a track record of value creation is very important. If a private equity firm carves out four or five businesses and the performance of the one of these declines, then the parent of that business might never sell another asset to the firm."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.