Poor relations: Endowments and foundations in Asia

With a few exceptions, Asia’s endowments and foundations lack the scale, sophistication and appetite for alternatives of their US brethren. Structural and cultural barriers maintain the status quo

Sophia University is unusual among Japanese educational institutions for having a 15% allocation to alternatives. Many don't have any exposure at all. Asked to explain the discrepancy, Masafumi Hikima, a professor and executive director for finance at Sophia, gives a matter-of-fact response: "Because I am here. The finance professors at most universities don't want to be involved in the endowment. The lack of expertise means they play safe with fixed income."

Hikima's previous career included stints as CEO of Nikko Asset Management and AllianceBernstein Japan. It is generally agreed that there are few working for endowments with this kind of experience – and it has an impact on alternatives. Hiroshi Nonomiya, representative director at local placement agent Crosspoint Advisors, estimates that no more than a dozen universities are actively investing in the space.

Even with experience at the helm, Sophia's portfolio is small and highly conservative compared to those of typical US endowments, which are recognized as thought leaders in sophisticated, long-term investment. The overall program is about $500 million, and the alternatives portion is primarily deployed in private real estate investment trusts. Stable cash flows are a priority. PE only gets a look in through a tiny allocation to impact investment.

For all the global interest in sourcing LP commitments from Japan, the country's universities represent an overlooked dot in the fundraising landscape for most private equity players. And in this respect, they are a microcosm of Asia's wider endowment and foundation community: sub-scale, short-staffed, facing impediments to growth – due to the way universities are funded and foundations are structured – and generally risk averse.

"Every university is trying to get more donations," Hikima observes. "But the tax deductions for donations are not as generous as in the US. On top of that, we don't really have a donation culture in Japan. We don't have many successful entrepreneurs who are willing to make donations on a massive scale."

Bigger is better

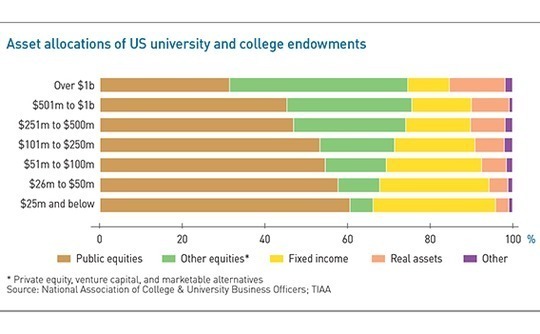

Size does matter in terms of an endowment or foundation's ability to address alternatives. A 2019 study of US endowments and education-related foundations by the National Association of College & University Business Officers (NACUBO) and TIAA found that those with over $1 billion in assets had an average allocation to PE, VC, and marketable alternatives of 43.2% with a further 13.5% in real assets. Below $1 billion, public equities and fixed income move into the majority. Below $50 million, the combined other PE and VC and real assets allocation is less than 15%.

Even though endowments and foundations in Asia trail their US peers in scale, the rule still stands. The Hong Kong Jockey Club is generally acknowledged as an outlier in the foundation space as the largest charity in the territory with HK$36.6 billion ($4.7 billion) in assets as of June 2019. It was one of the early movers into alternatives in Hong Kong, starting with fund-of-hedge-funds about 15 years ago. Private equity came later. The Jockey Club is now described as a large-check, high conviction investors capable of committing $100 million to a single fund.

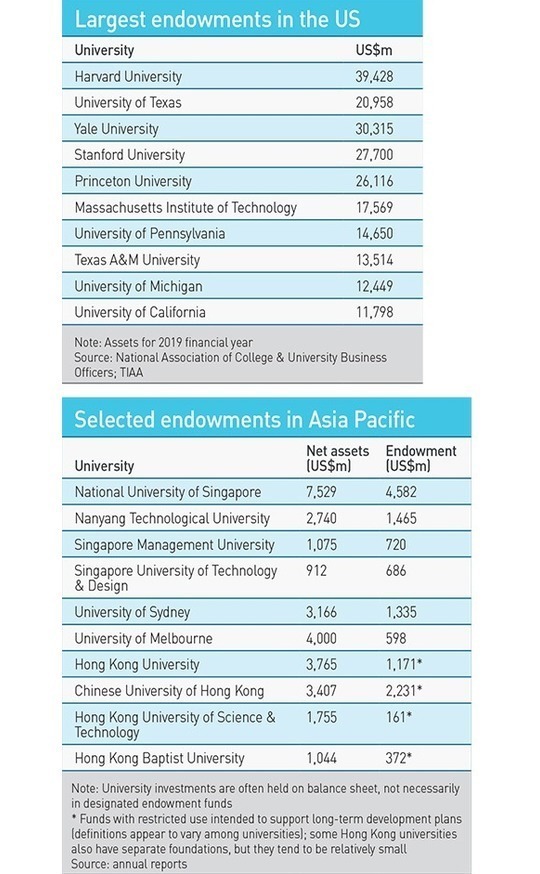

The National University of Singapore (NUS) enjoys a similar status among the region's endowments. With S$10.5 billion ($7.5 billion) in net assets and an endowment of S$6.4 billion for the 2019 financial year, it would rank among the top 25 US universities. The capital NUS has at its disposal is more than that of Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore Management University (SMU), and the Singapore University of Technology & Design (SUTD) combined.

The university has a private equity and real estate allocation in line with US endowments of similar size, which would put it at around 40%. Check sizes can vary greatly, but most sources put the average in the $40-50 million range. Like the Jockey Club, most of the NUS capital pool is devoted to re-ups; the program is 15 years old. Unlike the Jockey Club, it is broad in focus: a Southeast Asia growth fund would be considered on its merits alongside a global buyout manager.

"They are a very sophisticated institutional endowment, run in a similar style to US endowments in terms general allocation to alternatives. Historically they've been more invested in Asia, though now they are trying to rebalance," says one industry participant. "Check sizes are $30-40 million but they are consolidating relationships, so now we see them go to $50 million on occasion. They used consultants early on, but not anymore."

Insource vs outsource

NUS does retain some advisory relationships, but due diligence on managers is carried out by an in-house team of four, responsible for private equity and real estate. Size matters for NUS because it provides the budget for internal resources capable of building and overseeing an alternatives portfolio. The Jockey Club is the same. They do meetings with fundraisers, while others delegate this responsibility to advisors or go through fund-of-funds.

"It would be very difficult for us to invest in this area without a consultant. The consultant helps us with due diligence on managers because there are quite a number out there and then it helps us build a portfolio," says Dennis Yim, a senior finance manager responsible for investment and treasury management at Hong Kong University of Science & Technology (HKUST).

HKUST is arguably among the more progressive of Hong Kong's higher education institutions. It started investing in alternatives in 2013, initially focusing on hedge funds. There is now exposure across PE, VC, real estate and private credit, and in recent years the alternatives allocation has hit 10%. HKUST did this to diversify its source of returns and rely more on the skills of managers than macro trends. But net assets are still only HK$13.6 billion ($1.75 billion), the endowment is about $800 million, and there are two people overseeing all investments.

Advisors active in Asia suggest that $25 million is enough to build a private equity program with diversity across vintages, writing checks of $1-2 million per fund. Access would come through aggregate commitments sourced by the likes of Cambridge Associates and Mercer who divide them up among 20-30 clients and take responsibility for monitoring.

According to David Burke, founder and managing director of Makena Asset Management, a US-based outsourced CIO (OCIO) platform, it's only once an overall investment program hits $2 billion that meaningful in-house resources can be hired. In the sub-$1 billion space, the university CFO allocates part of his time to the endowment, receiving input from an advisory committee and a third-party consultant.

Universities sitting in between these two poles often take more of a hybrid approach, with internal staff playing a role in asset allocation and manager selection but outsourcing certain functions or even entire asset classes. "They could work with an OCIO and a consultant. If you don't trust going all in with one outsourced provider, split the allocation and have them watching each other. Then you move money one way or the other based on how people are doing," Burke says.

Based on the NACUBO-TIAA study, endowments with $250-500 million in assets have an average PE and VC allocation of 27.2%, plus 8.4% in real assets. For a $400 million investment program, that's $109 million and $33 million. Edward Grefenstette, CIO and CEO of The Dietrich Foundation, which has about $1 billion in assets, observes that it is challenging to build a VC portfolio comprising world-class managers below the $400 million mark. A fund-of-funds or OCIO is likely the better way to go.

At the same time, outsourcing may keep an endowment several steps away from capturing all the alpha – and not just because of the fees.

"In the small cohort of world-class managers, there is something vital about walking in with a card representing a single institution. Access may depend heavily on the attractiveness of your organization's mission," Grefenstette says. "GPs that are oversubscribed care about who they are getting money from and they prefer to help charitable organizations. It can be a lost opportunity when an institution outsources to an OCIO because, in the end, they become just another liquidity provider."

Advocates needed

Even in Asia, there are exceptions to the size rule. The Croucher Foundation, which was established in 1979 to promote science, technology and medicine standards in Hong Kong, is said to have a mere $300 million in assets yet a 40% alternatives allocation. It uses an advisor, but real impetus comes from a board of trustees and investment committee that are familiar with private equity. In contrast, one advisor recalls an investment committee member of another foundation refusing to countenance PE because the investment targets are not predetermined.

The importance of top-level support for an alternatives program cannot be underestimated, regardless of geography. While Japan's endowments are constrained by a lack of investment professionals in their ranks, a strong investment committee is perhaps more important in setting asset allocations. "If they are conservative, proposals in alternatives are not accepted," says Crosspoint's Nonomiya. "If the committee has a couple of people who are familiar with alternatives, they could push it."

This theory also goes some way to explaining why Singapore has the edge on the rest of Asia when it comes to endowments targeting alternatives. In GIC Private and Temasek Holdings, Singapore has two of the most sophisticated sovereign investors in Asia, with decades of experience in the asset class. From early on, GIC forged ties with US endowments. Leonard Baker, a partner at Sutter Hill Ventures who served 25 years on Yale University's investment committee, remains a member of the sovereign wealth fund's international advisory board.

"GIC has made strong use of alternatives for a long time – its comfort and experience are on a par with top US endowments – and senior people from GIC are on the boards of these local endowments," says Makena's Burke. "Singapore is such a small community that you get a cross-pollination of ideas. If you are at the NUS endowment and you have a question, someone from GIC is only one call away.."

The chairman of NUS' trustee board is a director at GIC and was previously president of Temasek. Several other board members have ties to these organizations.

Just as it's easier to win support for a foray into alternatives when a sovereign wealth fund executive advocating the strategy, one institution's success can stimulate others. This might be described as the "David Swenson effect" after the Yale endowment head who is credited with getting investment committees to think in an unconventional way about building robust, long-term portfolios. Swenson's impact is visible not only in his writing, but also in how many of his proteges make up the next generation talent in the US endowment community.

Advisors claim there is some evidence of this in Asia. They link the willingness of certain Singapore institutions to engage with alternatives to the example set by NUS. Apparently, some of the Hong Kong universities are reviewing their positions having seen what is happening elsewhere. "It leads to more conversations," says one advisor. "There are investment committee and finance office networks. They look at each other's numbers."

Structural impasse

However, this is unlikely to signal a wholesale change in behavior, rather an erosion at the margins – perhaps nothing more than asking an advisor for proposals into private equity. The public sector role in education financing is a disincentive to taking greater investment risk, even if the bulk of government support doesn't end up in the long-term portfolio. (Many universities in Asia do not invest solely from stand-alone endowment funds with specific deployment criteria, but from a central balance sheet.)

In Hong Kong, over half of recurrent university income is borne by the public purse. The University of Hong Kong, for example, relied on donations and benefactions and interest and investment income for just 9% of its revenue in 2019. Government contributions accounted for 50%. US institutions are more dependent on endowments to support their operating budgets, so there is a reason to pursue double-digit returns.

"Hong Kong institutions are well-funded now because the University Grants Council covers running expenses, wages and basic building. They want to use the endowment for mitigation – in case there is a change in government policy that affects running expenses or to pay for exceptional items like business schools," says Adeline Tan, head of wealth consulting in Hong Kong for Mercer.

She has experience in working with most of the leading local universities and believes only a few have a strategic and active allocation to alternatives of 20% and above. Others have made strategic decisions not to engage or they do so opportunistically.

Australian institutions are characterized by an innate conservatism towards alternatives for the same reason. There are about 40 universities nationwide with endowments ranging from A$50 million ($33 million) to more than A$2 billion. The University of Sydney sits at the upper end of this spectrum and its private equity allocation – 23% – is abnormally high, though much of it is channeled through fund-of-funds. About one quarter of its revenue came from the federal government in 2018.

Sydney observes in its 2018 annual report that the share of revenue coming from fees has risen considerably over the past decade as federal grants have declined, which suggests a greater role for private funding sources – currently 14% – in the future. Similarly, Yim of HKUST notes that some donors have called on the university to set up a US-style endowment that generates US-style returns. He admits this may require a recalibration of HKUST's investment strategy.

Few envisage a surge in private support as a realistic near-term prospect because it would require a wider shift in attitudes towards alumni giving. "The concept of private donations for general use that create excess endowment of which only a part is required to support the operating budget just isn't a phenomenon as prevalent in Asia. The same thing could be said for the tax incentives and general form of philanthropy and operations of foundations," says Chris Lerner, a partner at Eaton Partners.

Foundations first?

However, some industry participants identify foundations as potentially the faster growing area in Asia. While the nature of education funding and the perceived needs of educational institutions may constrain endowment size, more private wealth is emerging across the region, which leads to greater professionalization in management and diversity in deployment.

Tax confuses the issue by blurring the line between family offices and foundations. In the US, private foundations are distinct legal entities that qualify for favorable tax treatment but are subject to strict regulation, such as a requirement that 5% of its corpus is paid out each year in grants or charitable donations. Most Asian countries don't have this kind of regime and so family offices often use structures as they please.

For instance, Steve Kim, CEO of Korean institutional advisory firm Castling Capital, has scoured the local market for years in search of endowments and foundations that want alternatives exposure, but to little avail. The one mandate he did receive was to invest $80 million in international private equity for a museum foundation. Ultimately, it was a family-driven endeavor. The owners of the museum wanted to diversify their domestic real estate-heavy portfolios while learning more about PE. The foundation was their vehicle of choice for this.

The haphazard nature of these arrangements is expected to fade as wealth passes through the generations and family offices mature. First, more wealth will transition from operating companies to financial holding vehicles, allowing greater flexibility in deployment. Second, patriarchal interference in family office activity will ease as more responsibility is delegated to professionals.

"It is an evolution we've seen in the rest of the world," says Wen Tan, CEO of Azimuth Asset Consulting, an advisor to asset owners and asset managers. "You will get family offices forming foundations – often with dedicated investment teams – and these invest in a slightly different way from the main family pool. The family office will target assets that drive long-term returns and the foundation will prioritize interest income and cash flow to support projects."

Moving from an approach where philanthropic needs are met on an ad hoc basis to one in which interest income sustains activities in perpetuity represents a difficult philosophical leap. But as with endowments, there are experiences, success stories and role models that can be drawn on in Western markets.

"The US has a great number of institutions that have shown what can be achieved with a powerful source of charitable resources," says Grefenstette of the Dietrich Foundation. "Leading endowments and foundations in the US have shown how many societal challenges can be approached and mitigated by creative solutions that will not – and perhaps cannot – come from the public sector."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.