Portfolio: Unison Capital and CHCP

Through its Community Healthcare Coordination Platform, Unison Capital wants to bring efficiencies and economies of scale to parts of Japan’s healthcare sector that have been isolated from private markets

Shinsuke Muto is not your average doctor. The first decade of his career was spent in medical practice, including a two-and-a-half-year stint as court physician to the emperor and empress of Japan – a position that necessitated living in the imperial palace two days a week. But then Muto switched to a path taken by even fewer of his peers, working as a management consultant for McKinsey & Company and launching a home healthcare start-up.

Muto continues to juggle a portfolio of roles that straddles primary care, entrepreneurship and policy advisory work. This arguably gives him unique insights into the dynamics of a national healthcare system that must evolve if it is to overcome the challenges presented by an aging population and a potentially unsustainable debt pile. He is not reluctant to participate in the debate.

"I am a doctor and an entrepreneur. At the same time, I have been working for the government for a long time, advising the cabinet and the Ministry of Health, Labor & Welfare. I have been proposing for many years that hospitals and other medical institutions like pharmacies should be structured under a nationwide program and that we need to introduce a lot of new technology," Muto explains. "That's one of the reasons I left McKinsey. When I propose something, I want to do it myself. I'm not satisfied with restructuring the landscape; I want to be directly involved with my team."

Asked whether his background makes him well-suited to work with private equity, Muto demurs. He considers himself first as a doctor – he still sees patients – then as a manager; buying hospitals is someone else's job. Yet Muto's standing within the healthcare and business communities could prove a valuable tool for Unison Capital in its quest to not only cross the previously uncrossed line between hospitals and private equity in Japan, but fundamentally redraw it.

"He is well-known in the industry. Doctors and pharmacists respect him, which has a positive impact on deal sourcing," says Naoto Umezu, a director with the private equity firm. "The regulatory aspect is very important as well. As private equity investors in the healthcare sector, we must comply with government guidelines and policies. You have to understand those guidelines and then communicate with the government, explaining what you want to do and gauging the reaction."

Buy and build

The chain of events that led to Muto's appointment as chairman of Community Healthcare Coordination Platform (CHCP), a Unison portfolio company, is not unusual. The private equity firm is a familiar presence within the broader healthcare sector, having backed a string of pharmaceutical companies. It routinely dips into this ecosystem when looking for expert advisors. Muto was an acquaintance of Tsutomu Kunisawa, a Unison partner and healthcare specialist.

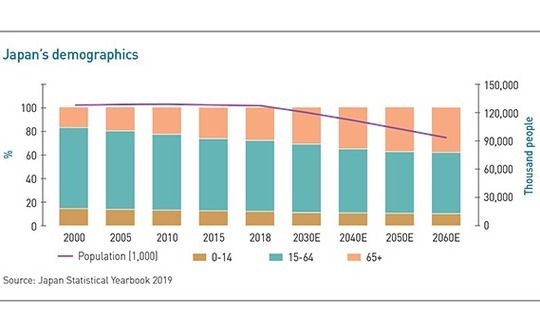

Neither is there anything striking about the core investment thesis. In 2018, 28.1% of Japan's population was aged 65 and above, up from 17.4% in 2000. By 2060, it is expected to be 38.1%. Demand for healthcare services is rising, especially the treatment of chronic conditions, and this is creating budgetary pressure. More than 80% of healthcare expenditure in Japan comes from public sources, compared to an average of 75% in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member nations. Private equity investors are busy searching for seams of value to mine.

The notion of aggregating services under a single platform is in line with the government's desire to establish an integrated community care system and ensure that the right care is provided in the appropriate location – for example, moving it from the hospital to the home. Inefficiencies arising from underused hospital beds and equipment and healthcare professionals who are widely dispersed across small work units should be eliminated. CHCP is intended to be an agent of change, leveraging its scale to promote collaboration between providers, introducing new technologies and establishing best practices.

"The pharmacy market is highly fragmented. There are 55,000 pharmacies in Japan, equal to the number of convenience stores, and the top five players only have a 10-15% share. In addition, providers have serious succession issues. They started in the 1970s and 1980s, so most of them are 60-70 years old," says Umezu. "We thought we could enter at relatively low valuations and bring about EBTIDA growth by optimizing operations and leveraging economies of scale."

This buy and build strategy was launched in 2017 and CHCP has since accumulated approximately 70 pharmacies. The goal is to reach 200-300, which would make the business a top-20 player nationally. Hospitals came into the picture last year. Having already invested nearly JPY6 billion ($55 million) in two mid-sized establishments, CHCP is targeting 20-30 with around 3,000 beds in total.

The platform has been sub-divided into two segments, one for pharmacies and the other for hospitals, each with its own set of operators who assume management responsibility once the dealmakers have completed their duties. Unison committed capital to the project from its fourth fund, which closed at JPY70 billion in 2015. With deal flow much stronger than originally anticipated, Umezu believes there is scope for CHCP to become a cross-fund investment. He estimates $500 million could be put to work.

Access issues

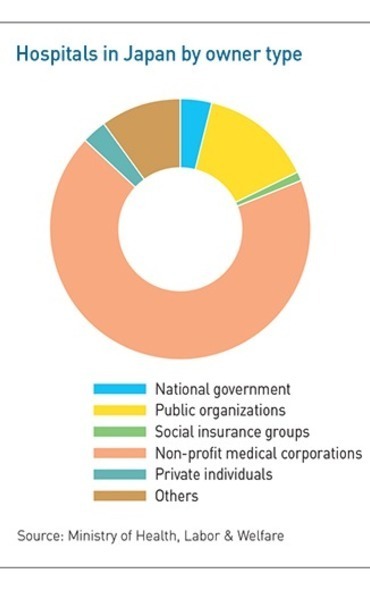

There is no shortage of potential targets in the hospital space. In 2016, the most recent year for which the Ministry of Health, Labor & Welfare has released data, Japan had 8,442 hospitals, of which 81% were under private ownership. Most of them are classified as small to mid-size. Only about 400 hospitals had more than 400 beds and those tend to be government controlled. Both public and private institutions face their own challenges.

"Over 80% of public hospitals are in debt and they survive through cash injections from the government. Private hospitals cannot access public funding, so they must generate their own cash flow," says Muto. "We are an aging society; we have more elderly people who don't need acute care. We need more community hospitals providing chronic or long-term care. The government wants private hospitals to do this, but they cannot make that shift."

These conditions create fertile terrain for a private equity roll-up strategy, but investors have been thwarted by a quirk in ownership: Four out of every five private hospitals in Japan are owned by non-profit medical corporations that are unable to distribute profits to shareholders in the form of dividends.

According to industry sources, there are only three ways to make money from hospitals: lease land to them, lend money to them, or sell non-medical services to them. CHCP is said to have opted for a version of the latter strategy. It refinances the hospital's debt and assumes control of the governance mechanism before setting up systems to provide management consulting and other services. The platform is equipped to take on all back-office functions if necessary, from drug purchasing to equipment rental.

The two existing hospital assets are Kumagaya Surgery Hospital, located in Saitama prefecture in the Greater Tokyo area and Heiwa Hospital in Yokohama. Each has approximately 150 beds. Operational improvement initiatives around management efficiency are currently being mapped out. But the key transition, for both hospitals, is from acute care to chronic care and rehabilitation. Kumagaya's bed occupancy is 60% because acute care beds – which account the bulk of capacity – are lying empty. CHCP's in-house view is that 85% is within reach once the focus shifts to chronic care.

While the skillsets required are somewhat different, the biggest obstacle in terms of staffing is institutionalized mindset. Changing tack after so many years maintaining the same course can be daunting. Part of Muto's role as a recognizable figure within the healthcare sector is meeting workers at all levels to explain the strategy and offer reassurances about the future.

"They are not used to being controlled by anyone apart from the CEO. They worry that, if they are bought by private equity, jobs will be lost or salaries will be cut," he says. "It's my responsibility to tell them why we are doing what we're doing, that it will maintain jobs and make the hospital better by providing services in relevant areas. If we get it right medically, we get more patients."

Agent of disruption

If selling the benefits of scale – whether that involves integrating different medical functions, negotiating bulk discounts on supplies, or having the flexibility to deploy staff where they are most needed – is one chapter of the platform story, then it is quickly followed by another on technology. Applications are wide-ranging. In a report published last year on Japan's transformation to 21st century healthcare, KPMG highlighted the power of gene analysis, data analytics and artificial intelligence (AI) in delivering one-to-one treatment, supporting drug discovering, and aiding diagnosis.

Umezu endorses these ideas, but also emphasizes a less flashy but equally fundamental benefit. "Right now, a patient fills out a form on arriving at a hospital, waits to see a doctor, then waits again for a prescription and payment. The whole process takes two or three hours, it's so inefficient. We can use online tools to improve this process. A lot can be done before the patient arrives at the hospital."

CHCP has found itself a strategic ally in the creative disruption drive in Globis Capital Partners, one of the leading domestic venture capital firms. The partnership is intended to deliver mutual gains by offering CHCP technology insights that keep it competitive and giving Globis-backed start-ups the opportunity to test product-market fit and access a wider customer base.

AI-enabled diagnosis and cloud-based enterprise resource planning (ERP) and workflow systems are expected to be among the key themes. The Globis portfolio includes AI Medical Service, an AI endoscope that aids cancer detection; Medley, Japan's leading telemedicine platform and software-as-a-service (SaaS) provider; FastDoctor, an on-demand doctor dispatching service; and Yoriso, a platform that connects bereaved families to funeral homes. Satoshi Fukushima, a principal at Globis, is bullish on the prospect of bringing these technologies into traditional hospitals, but realistic about the time horizon.

"The population composition of elderly people in Japan is expected to reach 34% in 2035. Given these conditions, more than other legacy industries, healthcare needs to be updated, automated with technologies, but it hasn't shown remarkable progress yet," he observes.

Perhaps digitization will take a firm hold over the coming decade as Japan's healthcare providers come to recognize the virtues of being leaner, smarter and more relevant. The lingering question is whether private equity can play the transformative role that Unison is seeking to achieve with CHCP. Much rests on its ability to reconcile the at times conflicting interests of all stakeholders and convince them that enterprise is not anathema to hospitals. "The social landscape is changing," adds Muto. "We want to be a good example of a private initiative."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.