PE & QSR: Ambition on a bun

Many private equity investors think they can make a fast buck from fast dining, but rolling out a Western-style brand in Asia requires discipline on valuation and competence in execution

Gondola Group was among the last remaining assets in Cinven's fourth fund, and as one LP tells it, exit prospects were uncertain. The portfolio company's primary business was PizzaExpress, which had 437 outlets in the UK and a further 68 internationally as of June 2014. Expansion in China by the brand's Hong Kong-based franchise partner had been measured, with about a dozen restaurants apiece in Hong Kong and the mainland.

Cinven wasn't willing to be so patient. In May 2014, Gondola opened a directly owned outlet in Beijing – as a showcase of what the brand might achieve in China when backed by enough capital and ambition. Two months after that, PizzaExpress was sold to China's Hony Capital for around $1.5 billion. By the start of the following year, Cinven had offloaded the remaining Gondola assets and generated a 2.4x return for its investors. The LP was "pleasantly surprised" by the outcome.

Hony's experience with the restaurant chain hasn't been as fulfilling. Adverse commercial conditions in the UK – still home to 480 of its approximately 620 outlets – has eaten into margins and left PizzaExpress potentially unable to sustain an already highly leveraged capital structure. Hony is considering restructuring options for a GBP1.1 billion ($1.4 billion) debt pile. At the same time, hype about China growth hasn't been matched by execution: there are still only 50 restaurants in the mainland.

Joel Silverstein, president of consultancy East West Hospitality Group, advised a private equity firm that was bidding for PizzaExpress in 2014. His assessment was that it wouldn't be able to open more than 50 new restaurants in China over a five-year period, citing high prices compared to other players in the market and relatively low product acceptance. The client revised downwards both its projections and the enterprise valuation it was willing to pay for the business, and duly lost out to Hony.

"They overpaid because they were too optimistic about China – one Hony executive told me they could open 500 restaurants, which I thought was crazy," says Silverstein. "What none of us saw coming were the problems in the UK, but the way you manage your risk is through the valuation. You put in a buffer in case stuff happens. The problem is there has been too much money chasing restaurant deals in Asia, so investors lost their discipline. Overpayment leads to subpar returns."

Preferred partner?

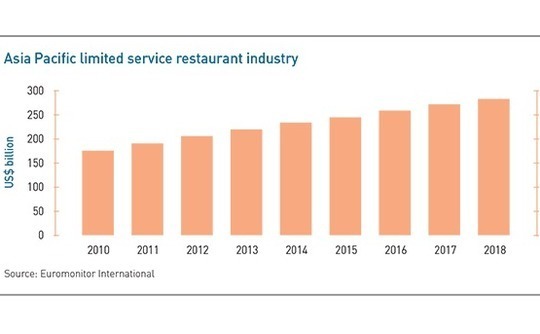

The attractions of quick-service restaurants (QSR) to private equity are obvious: it is cash generative, conducive to rapid rollouts, and plays into Asia's broad consumption themes. The business model can also be reassuringly predictable. On signing a master franchise agreement with a brand owner, the franchise holder commits to a certain pace of expansion and expenditure and a series of royalty payments based on store numbers and revenue. But the best-laid plans can go awry if projections are too ambitious, execution is flawed, or a brand just doesn't catch on locally.

"It's like building a wall, each brick is a new store. Some stores are more profitable than others, so the bricks aren't all the same size, but you can build relatively quickly. If a brand is recognized, there might be little ramp-up period," says Nick Bloy, a managing partner at Navis Capital Partners, current owner of Dome Coffee in Australia and previous owner of Dunkin' Donuts in Thailand and KFC in Hong Kong. "But you must watch out for fads, where the economics are initially great and then plunge after two years."

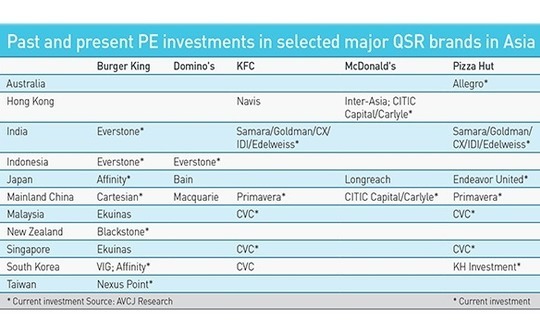

There is a long history of investment in Western-style QSR brands in Asia. One of the first came in 1974 when Inter-Asia Venture Management launched McDonald's in Hong Kong. It proved a successful investment, even though the company was forced to leave its first premises when the landlord called a 300% rent hike. AVCJ Research has records of more than 20 current private equity investments in brands ranging from Domino's to Wendy's and in geographies stretching from New Zealand to India.

Restaurant Brands International (RBI), owner of Burger King, Tim Hortons and Popeyes, would likely disagree with this assessment. The company, in which 3G Capital is the majority shareholder, currently works with private equity firms as master franchise partners in China, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, India, Indonesia, and New Zealand. Over the past seven years, the number of Burger King restaurants in the region has risen from 1,000 to around 3,000.

In several cases, PE firms replaced corporates as master franchisors with a brief to reinvigorate unloved, undermanaged and often undercapitalized businesses. For example, when VIG Partners bought Burger King Korea from Doosan Group in 2012, it was a non-core subsidiary that required an entirely new senior management team. Nexus Point Capital was awarded the Taiwan franchise two years ago after RBI took it back from the corporate incumbent. The notion of private equity as a focused partner with limited delivery timeframe is compelling, but RBI claims to be agnostic as to the source of capital.

"The key to success is having the right partners and we work with corporates, family offices and private equity all over the world. Every market is nuanced," says Sami Siddiqui, president for Asia Pacific at RBI. "We didn't enter China in 2012 [when RBI teamed up with Tab Food Investments, its master franchisor for Turkey, and Cartesian Capital Group], we entered well before that. But it took time to find the right partner and structure the right agreement."

In and out

RBI was a relatively early adopter of master franchise agreements whereby individual partners receive exclusive development rights for entire markets in Asia. Under the traditional US model, franchisees operate single outlets or limited regional territories, perhaps making as much money from sale and leaseback of the land on which a store stands as from the store itself.

While there is some sub-franchising in Asia, notably in more mature markets such as Australia and Japan, most international brands prefer to deal with a single owner-operator. That group may have the right to sub-franchise if certain performance targets are met. In China, the initial problem was a lack of potential franchise partners. Then it became finding partners that could be trusted. Franchisors have asked franchisees to put money in escrow accounts or buy goods and services instead of paying a percentage of revenue due to concerns about accounting accuracy, industry sources say.

KFC and McDonald's entered China as owner-operators of their own stores and it is only relatively recently that they switched to master franchises. Yum Brands spun out its China entity into a separate listed entity in 2016, with backing from Primavera Capital Group and Alibaba Group's Ant Financial. A year later, McDonald's followed suit, carving out its mainland China operation and selling an 80% stake to CITIC Capital, CITIC Group, and The Carlyle Group.

Indeed, the McDonald's transaction was in part driven by the company's hit-and-miss experiences with franchising. In 2012, a US-inspired dual model was adopted, comprising small-scale franchises for existing stores at local level and provincial level development agreements with minimum store opening requirements. Five years on, about 600-700 of the 2,500 stores in mainland China were franchised out and the provincial businesses were underperforming.

Recognizing the approach wasn't working but still keen to increase the franchise percentage globally from 83% to 95%, McDonald's looked for a master franchise partner, ideally a corporate that would stick around for the long term and leverage relationships with government and property developers. CITIC Group was drafted in by the financial sponsors to add strategic heft.

D.J. Luo, a managing director at CITIC Capital, suggests the franchisees struggled because they were not sufficiently financially committed, young and inexperienced, or unwilling to devote the time required to make it work. "From day one, the consensus view was that we would grow the business by ourselves instead of granting more franchises," he says. "We will stick to our commitment to open more directly owned stores and pursue aggressive expansion."

McDonald's was also motivated to sell by the long road to recovery following a food safety scandal in 2013 and the fact that it didn't enjoy a market-leading position in China. This is blamed to varying degrees on the absence of a medium-term development plan and a failure to localize the product offering. There were more than 5,000 KFC outlets nationwide when the McDonald's deal was announced. Even if the PE buyers achieve their goal of 2,200 new store openings by 2022, McDonald's will likely still trail KFC by a sizeable margin.

For all but a handful of brands, of which McDonald's China is one, this competitive dynamic could be a turnoff for private equity. It is generally agreed that frontrunners enjoy inherent advantages, such as access to the best locations and public recognition, which make them difficult to reel in. There must be a compelling reason – such a strong brand – to back lower-tier player.

"To do QSR right, you need a strong brand. You might be paying up to 5% of your top line to the franchisor, so you better make sure the brand is worth what you are paying for," says K.C. Kung, founder of Nexus Point. "The margins in QSR aren't great, usually below 20%. Suppose your margins are 15% but you need to pay a 5% royalty, your margins drop to 10%, and that's one-third gone. Whether it's the brand itself or the value the franchisor brings you through, for example, bulk purchase discounts or marketing know-how, you need to make up that 5%."

Brands apart

Brand strength is often synonymous with ability to scale, but some investors have built successful second-tier businesses through differentiation. Earlier this year, Proventeus Capital exited the Philippines franchise of Kenny Rogers Roasters with a more than 5x return, having increased the store count from 35 to 90. This is a fraction of McDonald's or Jollibee – which do follow small-scale franchising models in the country – but Proventeus delivered revenue growth by focusing on a market niche.

"Whenever you have a dominant local brand you should avoid that segment. Taking it on is expensive and it's a 10-year game. Few funds have that level of patience," says Lew Oon Yew, the firm's managing partner. "One of the things that attracted us to Kenny Rogers was its positioning in the healthy segment, offering roast rather than fried chicken as well as salads. It had better food, better ambiance and a higher price point than the big brands, and it had been there for 15 years, so the business was proven."

The Longreach Group took a similar approach to Wendy's Japan, despite the US burger brand's previous failures in the country. Instead of just taking the master franchise, the private equity firm engineered a merger with First Kitchen, a Suntory Holdings subsidiary with 136 existing locations. This effectively saved it the trouble of building out a physical footprint and a workforce in a market known for expensive real estate and labor shortages.

So far, 48 of those locations have been converted to the Wendy's First Kitchen model, which combines the Wendy's burger menu with First Kitchen's offering of pasta, salads and desserts. The aim is to create a diversified menu and an upmarket service that appeals to a broader demographic, thereby avoiding head-to-head battle with McDonald's and Mos Burger, which have 2,900 and 1,300 outlets, respectively.

According to investors with exposure to the QSR space, marketing is rarely a stumbling block, but adherence to kitchen best practices and product standardization is scrutinized. Several Asia-based PE executives have undergone training with RBI and worked shifts at Burger King in Singapore, so they fully understand the process and culture. Guidance from brand owners is valued because they are equipped with in-house resources and have seen what has and hasn't worked across multiple markets, yet tensions can emerge if the permitted degree of localization is less than the franchisor would like. Food is an obvious sticking point.

"It's not just a case of ensuring it is consistent with what Burger King stands for but who the suppliers are and meeting quality assurance standards," says RBI's Siddiqui. "We try to have a close relationship with management at the ground level. We have global specifications for flagship products like the Whopper, but in India for example, the crispy veg patty is unique to that market. Our product innovation team worked with the culinary team at the franchisee and the suppliers to come up with something."

A new or modified recipe typically undergoes extensive tests and then trialed in a handful of restaurants before getting the green light to launch. Sometimes successful concepts are given an even wider audience. During VIG's ownership of Burger King Korea – it exited to Affinity Equity Partners in 2016 – the four-cheese Whopper was developed and subsequently rolled out in several other markets.

This attention to detail on menu is not limited to RBI. McDonald's engaged in lengthy discussions with the private equity owners of its China franchise as to whether muffins should be the sole breakfast staple. The global brand had previously shut down a move to sell congee. The franchisor argued that for breakfast to grow as a platform in China, McDonald's must adapt to local tastes.

"We worked closely with McDonald's global, researched it properly, and together came to the conclusion that congee was indeed the right product," says Luo of CITIC Capital. "You need the right infrastructure to do that. We worked with third-party aggregators like Meituan-Dianping and Ele.me, collected data points, and identified key SKUs [stock keeping units] for development. Now congee has become a key driver for our breakfast business."

Seeking a balance

The trick of localization is offering enough familiarity to entice consumers without undermining the brand integrity of the franchise or eroding the efficiencies achieved through standardization. Tay of LTCV suggests that a Western QSR chain must include a Chinese element in at least 15% of menu items to get people through the door. But it must first arouse curiosity to make them cross the street and that often means emphasizing Western heritage, for example through celebrity endorsements.

There are some concepts that simply don't sell. CVC Capital Partners failed with KFC in Korea because it was unable to carve out a niche in a market overflowing with local fried chicken establishments. RRJ Capital and Jollibee raised eyebrows in 2014 when they took over the Dunkin' Donuts franchise for China given scant evidence of any meaningful local demand for the pastries. "Krispy Kreme failed. Mister Donut failed. Donut King failed. Dunkin' Donuts failed twice. How much more pain and suffering do you want?" asks Silverstein of East West Hospitality Group.

Others just don't sell as much as expected, usually because investors overstate the expansion opportunity or underestimate the competitive threats in their target market. Strong management is essential to QSR rollouts, which is why PE firms recruit leaders from a seemingly bottomless pool of former Yum Brands and McDonald's executives. They tend to be the first ones to get fired when things don't go according to plan, says Tay. Struggling franchises backed by an impatient GP have been known to go through a string of CEOs before handing power to the CFO as a last resort.

"That's usually a disaster," Tay explains. "The CFO is incredibly conservative, and he only listens to the private equity guys on the board. The fund life is running out, so they tell him there's no more money to spend, nothing for marketing, and any growth must be organic. The CFO is simply there to cut costs, make the numbers look good, and sell the company. But decision making based purely on financials often doesn't cut it in F&B."

Once a restaurant brand gets caught in a downward spiral it is very difficult to recover, as evidenced by a general reluctance to take on turnarounds. Picking the right concept at the right time – and paying a sensible valuation for it based on a sustainable business model – is therefore incredibly important. If these conditions cannot be met, the smart money walks away.

"After we sold Burger King Korea, so many people came to us with dining franchises. We turned them all down because we couldn't find anything with scarcity value," says Jason Shin, a managing partner at VIG. "It is hard to find a recognizable brand or concept in a space that isn't so crowded, but where you know there is consumer growth."

SIDEBAR: Franchisor vs franchisee

When Allegro Funds acquired Pizza Hut Australia in 2016, the delivery chain was badly in need of restructuring and rejuvenation. The private equity firm had faith in the product – it performed well in blind tastings – but the technology offering was outdated and the franchisee network inefficient, with 220 partners for just 270 stores. These franchisees were also in open revolt.

One of the reasons Yum Brands sold the business was a breakdown in relations over a A$4.95 ($3.40) pizza. In launching this special offer against their will, the franchisees claimed that Yum had no interest in their profitability and therefore had a conflict of interest. They took the company to court but lost. The appeal, also unsuccessful, was heard after Allegro took over. One of its first tasks was rebuilding bridges.

"We listened to them and almost everything they raised was valid. Mostly, they just wanted to be listened to, and to see us acting on their recommendations," says Chester Moynihan, a managing partner at Allegro. "You must have a healthy franchise network with a profitable economic unit. If you don't, existing franchisees will become disengaged and potential new franchisees won't invest."

The brand owner-franchisor and franchisor-franchisee relationships are intended to deliver an alignment of interests, but sometimes tensions flare-up. The former's main income stream from the latter is a royalty based on revenue, not profitability. While they want those streams to be consistent and long duration – so there is reason to help the franchisee build a sustainable business – it isn't unknown for them to push for an ambitious growth plan or an aggressive price-led promotion.

"The franchisor model is a bit more predictable in projecting growth. If there is a lot of franchising, they get a percentage of revenue and it's predictable because stores generally don't halve their previous revenue. The fixed cost base is lower as well because they aren't paying for rent and labor," says David Gross-Loh, a managing director at Bain Capital, which has served as a brand owner and a franchisor. "Such businesses are a lot more profitable, they are high margin, and they trade for very high multiples."

Navis Capital Partners has also fulfilled both functions, previously as a master franchise holder for Dunkin' Donuts in Thailand and KFC in Hong Kong, and currently as the owner of Australia-based coffee chain Dome. Nick Bloy, a managing partner with the firm, has no desire to become a franchisee again, citing the unpleasant experience of being squeezed by an aggressive franchisor at one end and a rent-hungry landlord at the other.

"The returns are not as good from franchisee businesses. It is much better to be a brand owner, even if you are not franchising to other people but rolling out your own brand," he says. "You don't have to pay an upfront franchise fee, a fee for every store you open, a cut of revenue, and make contributions to a central marketing fund."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.