Philippines PE: Power dynamics

A virtually impenetrable middle market under the control of incumbent conglomerates is the least governable of the systemic obstacles facing private equity hopefuls in the Philippines

A great macro story doesn't necessarily translate into a great deal environment. In fact, these two backdrops are sometimes reversely correlated because a robust economy can entail entry barriers that are too high for new investors. Understanding this phenomenon helps elucidate the under-penetration of private equity in the Philippines to date, but with the right contextualization, it could also encourage new entrants by demystifying one of developing Asia's more frustrating paradoxes.

The headline figures for the Philippine economy are among the sturdiest in the region, with GDP growth holding at around 6% a year, a youthful population of 105 million, and a widening middle class. Moreover, there is also a general belief that fiscal issues such as currency volatility have been well managed in a business-friendly policy environment, ongoing tax reform notwithstanding. Foreign direct investment eroded slightly in 2018 to $9.8 billion, but this is still almost double the annual average during the previous two decades.

As is the case in much of Southeast Asia, domestic consumption, not international trade, is the dominant driver of growth. This has led to optimism around the possible impacts of the US-China trade war, but it also highlights one of the key challenges to sustaining the boom: diversification of the economy through internationalization. The main constraints to PE participation in this process are infrastructure bottlenecks – which are likely to be embraced by problem-solving GPs – and barriers to competition presented by a M&A market dominated by cashed-up, well-connected and conservative family conglomerates.

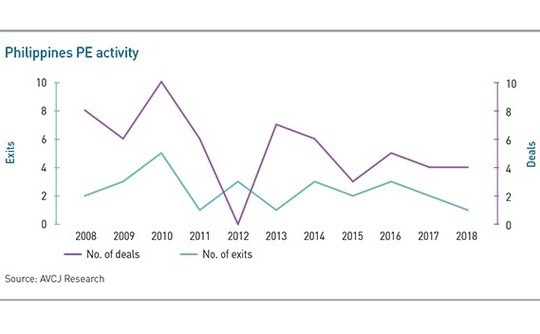

The result has been a remarkably underdeveloped private equity space. During the 10 years to 2018, the number of PE deals in the country per year, excluding VC, peaked at 10 in 2010, according to AVCJ Research. The best year for exit volumes during the period was 2010, with five, again excluding VC. Only three local middle-market PE firms have gained detectable momentum. Navegar closed its first fund at about $100 million in 2013 and is now targeting $150 million for a follow-up. Sierra Madre raised $50 million for its first fund in 2017, and Argosy Partners raises capital on a deal-by-deal basis.

Small bites

The key commonality here is a focus on reduced operational scope. Larger regional or global GPs have enjoyed little success penetrating the Filipino M&A market partially because they need an on-the-ground presence to get comfortable with locally nuanced risks related to business sector corruption. However, the bigger deterrent has always been bite-size. Local PE players haven't necessarily had the option to go large, but they have learned nevertheless that targeting companies invisible to the conglomerates is the only reliable way to get a piece of the action.

"If you're going to have any success in this business, you need to adapt to the reality of what's on the ground. There's no point wishing it were different," says Alasdair Thomson, a co-founder and managing partner at Sierra Madre. "When we set up our fund, we formed a view that there was a gap in the market at the smaller end of the SME [small to medium-sized enterprise] stage, which is below the radar screen of most of the bigger conglomerates. We're not going to run headlong into one of those guys every time a deal comes up."

Thomson estimates that the Philippines' largest 260 companies represent half of the local economy, leaving about 1.5 million micro-enterprises at the bottom and some 10,000 investible SMEs in the middle. The government has recognized that this opportunity set is too shallow to attract outside investors without leveling the playing field and launched the Philippine Competition Commission in early 2016 to ramp up international M&A. But after nearly four years, the antitrust authority has blocked only one would-be monopoly, a sugarcane rollup planned by local food giant Universal Robina.

"The conglomerate presence across the economy is great for the growth of domestic industry, but it sucks out the requirement for institutional capital," Pai told the AVCJ Philippines Forum last week, adding that the early-stage ecosystem wasn't sufficiently feeding pipelines for middle-market GPs due to a combination of competition from other sources of capital and a lack of appreciation for PE value-add. "Entrepreneurs are beginning to see life beyond selling to a conglomerate. There has been some change in terms of how they look at institutional capital, though not enough."

The idea that the best openings are at the smaller end of the market is perhaps best crystallized in an unusually venture-style play by KKR, which joined China's Tencent Holdings last year in a $175 million investment in financial technology developer Voyager Innovations. The deal stoked middle market hopes because Voyager was backed as a unit of telecom leader PLDT, not an independent start-up. Still, PLDT's retention of control offered a reminder that local conglomerates have shown little appetite for selling divisions, which complicates exit outlooks for PE players in such deals.

KKR sees these family-run groups as well capitalized on the back of recent GDP growth, low on debt, willing to invest for the long term, and bullish about their home market. It has also charted difficult levels of market concentration, estimating that the three largest family groups control more than half of the companies on the Philippines Stock Exchange. Michael de Guzman, a managing director at KKR who previously served as head of the Philippines for Credit Suisse, sees patience and relationship building as the key inroads. He says KKR has spent 10 years just trying to get to know local conglomerates.

"We may do a transaction, we may not do a transaction in the next 5-10 years, but at least we're constantly monitoring what they're doing so when the time comes, we're comfortable, we have been meeting with the chairman or management for many years and have a good feel, rather than just making a situational, one-off transaction," says De Guzman. "We know we have to be invited by these families to come in, and therefore we just need to show them what is happening outside, and that internationalization and regionalization is imminent."

Among the whales

The patient approach paid off this week with confirmation that a KKR-led consortium would invest about $680 million for a substantial minority stake in Metro Pacific Hospital Holdings, the country's largest healthcare operator. The deal – which saw GIC Private rollover and add to an existing investment, effectively nixing a local IPO plan – is also useful in illustrating the interconnected nature of the local conglomerate economy. Metro Pacific's parent company is a subsidiary of a Hong Kong entity, First Pacific, which also controls PLDT. The plan is to build out Metro Pacific's domestic hospital network.

In the case of Voyager, KKR's experience in fintech disruption and financial inclusion business models was an important draw card versus local industrial capital. But for most private equity firms, different angles will need to be prioritized, especially in the areas of cross-border connections and overall professionalization. GPs must flex their strengths in recruiting talent for regional expansions in a timely manner, while also stressing value-add capacity in governance, including the environmental, social and back-office accounting competencies needed to attract international partners.

Among the segments that have proven most amenable to this approach in the Philippines to date is business process outsourcing (BPO). Local BPO operator SPi Global offers a case in point, having been passed between several private equity firms. Partners Group, which set up its Manila office in 2016, acquired the company for $330 million the following year, providing an exit for CVC Capital Partners.

"Conglomerates have a lot of strengths and they operate their business very well, but that level of concentration does suggest there isn't enough competition, and it does reduce vibrancy. Actors like us bring in a lot of global best practice and a lot of capital efficiency," says Cyrus Driver, a managing director at Partners Group, noting that value-add efforts for SPi included two bolt-on acquisitions. "We keep looking for those opportunities where there's a reason for us to be a good owner of the business in the next leg of its journey, and we have to be patient and wait for those opportunities."

SPi's PE-guided story still betrays the ubiquity of conglomerates, however, considering CVC acquired the company in 2013 as a carve-out from PLDT. Teasing out transactions of this kind has clearly proven more feasible with heavyweights like PLDT, which are better known for disciplined approaches to M&A and engaging counterparties in a more calculated, dispassionate way. Entrepreneurially held conglomerates, which hang over the bulk of the SME opportunity set, present more challenges around getting familiar. As a result, inbound PE has yet to trigger a sizable carve-out market.

George Uy-Tioco, head of M&A at BPI Capital, the investment banking unit of Bank of the Philippine Islands, says he has interacted with a number of conglomerates that have flatly claimed to have never sold a subsidiary business. He describes deal making in this environment as a relationship game, not just in the context of founder-entrepreneurs but also in terms of banks and financial services providers as well. It is worth noting that BPI is controlled by Ayala Corporation, one of the Philippines' most powerful family-run firms.

"When you're dealing with advisory for an M&A transaction, in general, they won't necessarily take you on as an advisor just because you're their biggest bank," Uy-Tioco says. "It's a question of whether they trust you or not to share that strategic vision with you. But it helps if they have family members who've had some exposure to some kind of professional work either with another investment bank, or a KPMG and the like, or have studied abroad. Your ability to gain their trust and handhold them through this process is what helps you get the deal."

Going global

There are a couple of emerging trends that bode well for deal making in this landscape. First, local entrepreneurs, young and old, are said to increasingly see their businesses as projects to be eventually sold rather than preserved across generations. This development has come with a recognition that taking a company to the next level often means having a partner with skin in the game, but it moves at word-of-mouth speed and remains limited to the accumulation of positive experiences with PE.

Second, the Philippines has seen a distinct uptick in conglomerate-driven outbound M&A, which will inevitably inject more global viewpoints and best-practice standards into the local market. Standout transactions in recent years include Monde Nissin's $830 million acquisition of UK-based Quorn Foods and Emperador's $730 million buyout of fellow beverage maker Whyte & Mackay, also in the UK.

Notable PE exposure to this momentum includes Australia's Pacific Equity Partners exiting Griffin's Food to Universal Robina in an approximately $240 million deal, as well as Jollibee Foods paying $350 million for US-based The Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf. The latter set up exits earlier this year for Advent International, CDIB Capital, and Mirae Asset Private Equity.

The hope is that activity of this kind will support local sentiment for PE and more internationally minded strategies among local founders. But the question with the Philippines is always when. Saima Rehman, an investment officer for the International Finance Corporation focused on PE in eastern Asia Pacific, finds that while the country is seeing a fair amount of strategic M&A activity, LPs will remain wary of embracing the market until exit numbers pick up.

"You have maybe one or two stories every one or two years that make the headlines. That's not going to bring international institutional capital flooding into this market," Rehman says. "You need fund vintages that have gone through the entire PE cycle and come back to investors on their roadshow with pitchbooks saying ‘we've given our investors back 3.5-5x their money.' You don't have a single GP in the market that has been able to do that."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.