Emerging Asia healthcare: Pilot programs

Buy-and-build strategies, a mainstay of the PE toolkit in developed markets, are gaining exposure in emerging Asia’s healthcare sector. Proving a viable exit path will be the key to widespread adoption

Over the past three years, Asia Healthcare Holdings (AHH) has been quietly devising a new playbook for PE participation in India's healthcare sector. Starting with the acquisition of Cancer Treatment Services International (CTSI) in 2016, the TPG Growth-backed investment platform has focused on acquiring companies with a limited presence to make them significant players in the country.

This buy-and-build approach is familiar to investors in developed markets, where platform strategies are commonplace in healthcare. Emerging Asia has been slower to adopt the tactic. Concerns persist about the difficulties of taking small operators in highly fragmented healthcare markets to the scale required to become an attractive exit prospect – and all within the limited timeframe of a private equity investment. But AHH insists it can work.

"Build versus buy has always been a topic of debate in Asian private equity, and more often than not the build element gets pushed aside and the investor decides they're better off taking a minority position in an asset and letting the founders grow it," says Vishal Bali, executive chairman of AHH. "We took majority stakes in these early-stage companies because we knew we had the management bandwidth to build out for the future. That equation has worked very well for TPG Growth and AHH."

AHH is one of several PE-backed platforms that are pushing the buy-and-build strategy in Asia as a way to create valuable, differentiated assets in the region's booming healthcare sector. While investors see potential in the model, its long-term suitability for emerging markets in general and Asia's highly differentiated economies in particular is unclear. Adoption is likely to remain limited until managers can consistently deliver exits.

"There certainly is some inspiration that one can take from developed markets about building large, scalable businesses," says Abrar Mir, co-founder of Southeast Asia-focused healthcare investor Quadria Capital. "But the dynamics in Asia are extremely different than Europe and the US, and a business model that's been built successfully there may not be directly applicable."

Meeting a need

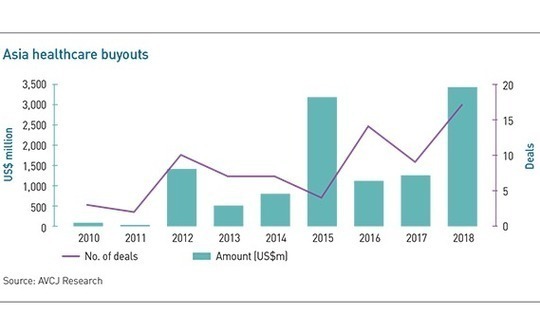

The healthcare opportunity in Asia's emerging markets is well known. According to AVCJ Research, China, India, and Southeast Asia (excluding Singapore) have collectively drawn more than $11 billion for buyout deals since 2010. Last year was a record in terms of both deal volume and capital, with $3.4 billion committed across 17 transactions. China accounted for the majority, with $2.4 billion committed to seven deals, but India and Southeast Asia have received significant investment as well.

A common thread across all markets is the growing incidence of chronic ailments such as obesity, cancer, and cardiac disease as average ages rise, and populations move toward more Western-style, sedentary lifestyles. As public healthcare systems are poorly suited to care for such conditions, governments are increasingly looking to the private sector to handle these issues before public providers are overwhelmed.

"When a significant part of your fund is in a sector, you need to start thinking about that sector much more proactively, and a big theme emerging for us is to look at fast-growing, fragmented spaces within healthcare, and see how we can consolidate them," says Arjun Oberoi, a managing director at Everstone and vice chairman of Everlife. "Ascent was the first such play for us, and over the last three years we've built it into India's largest pharmaceutical distribution platform."

Several of Everstone's global peers have launched by buy-and-build initiatives in Asia. TPG Capital launched Southeast Asia-focused specialty hospital investor TE Asia Healthcare in 2014, and its growth arm has backed AHH since 2016. KKR is building the China-focused hospital platform SinoCare Group around Hetian Hospital Management, which it acquired last year, and holds a 49% stake in Indian hospital group Radiant Life Care. The latter is pursuing an M&A strategy.

Everlife, which recently made its first investment in India with CPC Diagnostics, is an outlier among these platforms. Hospital-focused holding vehicles tend to stick within a single region, or a single country in the case of China and India investors, because growing a customer-facing business like a hospital means focusing on the nuances of each market.

China challenges

In China, the role played by the state is a key factor. The government can be an obstacle, a competitor, or an ally depending on the situation, in ways that can either help or hinder a healthcare consolidation play.

First, any private equity investor trying to build a broad hospital platform in China must reckon with the country's public healthcare system, which covers more than 90% of the population and is the first choice for most patients. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China's public hospitals received 2.5 billion patient visits in 2016, compared to 360 million for private facilities.

Despite overcrowding, public hospitals continue to be preferred among the general population because they are seen to provide access to the best doctors in the area across a range of specialties, something their private-sector counterparts cannot match. Private platforms must leverage their capacity to compete with public hospitals.

"To have the top medical experts for that many specialties would take too long for a single private hospital," says Jenny Yao, head of healthcare for KPMG China. "But as a platform company with modern technology you can have the experts in the places they are needed most, while still being available for consultations when a patient in another location needs advice, achieving economies of scale."

Private operators can also find greater opportunities in lower-tier cities and rural areas where the supply of public hospital beds is limited. According to the National Health & Family Planning Commission, in cities ranked fourth-tier or lower, public hospitals have fewer than three beds per 1,000 residents.

Those who cannot access quality healthcare at home tend to go to the major cities, further increasing pressure on public facilities there. As a result, the government has eased restrictions on private investment in healthcare in recent years. SinoCare, which focuses on lower-tier areas, hopes to take advantage of these trends.

"The healthcare reforms are pushing people to get treated in their local hospitals, because of the growing levels of chronic diseases and long-term conditions," Yao says. "There are a lot of places in the lower-tier cities where the private sector can play, and government policy is also moving in that direction."

Private equity-backed platforms may also have an advantage thanks to mounting emphasis on compliance. Operators with a history of obeying the regulations will likely have a much easier time than those that constantly draw scrutiny for suspected wrongdoing.

"The administration's focus on corruption means larger companies that follow the rules have a chance to gain market share," says Steven Wang, co-founder and managing partner at China-focused healthcare investment firm HighLight Capital. "While healthcare companies may have cut corners in the past, in the future everyone will need to follow the standards, and that will help encourage industry consolidation."

In India, aspiring platform builders face more of a societal issue, with the country's multiplicity of languages and cultures limiting the mobility of doctors in ways not seen in other countries. Most doctors rely on referral networks within a single city and these are hard to scale quickly. Even larger hospital brands tend to be limited to a single region due to the challenges of doing business with unfamiliar customer groups.

Buy-and-build strategies, which enable outside operators to enter new markets without taking construction risk, are a possible solution. Hari Buggana, a managing director of Invascent Capital, points to Sunshine Hospitals, a provider of orthopedic, cardiology, and neurology care in Hyderabad, as the kind of asset that would be attractive to a prospective national operator.

"At some point, any larger platform might look at a chain like Sunshine and see this as a bite-sized acquisition that can be bolted on or co-branded, and that's a way to achieve further expansion," says Buggana, who is an investor in the company. "It's much more efficient than greenfield expansion, which is very difficult to do in Indian healthcare."

Despite this incentive, consolidation plays have been rare in India. However, the government's new National Health Protection Scheme (NHPS) is projected to lead to roll-ups on a much larger scale. NHPS plans to provide 100 million poor and vulnerable Indian families with insurance coverage of up to INR500,000 ($7,200) per year, potentially unleashing considerable pent-up demand from an underserved population. But investors expect the benefits to be weighted toward those players that can handle the government's well-known problems with efficient reimbursement.

"The government tends to pay after six to nine months, and only a very large, well-funded platform would have the financial capacity to wait that out," Buggana says. "Smaller hospitals may accept some of these patients, but they're going to struggle because it's hard to fund the delayed payments. So there's a strong rationale to scale up for those that have the ability to do so."

The fragmentation factor

In Southeast Asia, the biggest challenge is market fragmentation. Even more so than in India, the region is a patchwork of languages and cultures, with the added frustration of varying regulatory and political frameworks, and the logistical barriers of doing business across several island nations. The markets also have widely varying levels of development, ranging from modern economies like Singapore to Myanmar, which only recently emerged from years of military rule.

TE Asia has tried to turn the regional variations in Southeast Asia to its advantage by emphasizing communication and knowledge sharing between its portfolio companies in different markets, which include a cardiovascular hospital in Malaysia, an oncology center in Hong Kong, and a dermatology clinic in Thailand. The platform hopes to build a network of experts in various specialties that can bring best practices to patients around the region.

"We are in a region where patients are driven by doctors – we've not reached the point where we have a few key institutions that people go to because of the reputation of the institution," says Aik Meng Eng, CEO of TE Asia. "Our model is to get the best doctors together to practice medicine effectively and try to increase both accessibility and standards of care in the region."

Despite obstacles to implementation, buy-and-build platform operators and their backers are confident that the strategy can work if paired with the right management team. TE Asia, AHH, Hetian, and Everlife are all headed by former hospital executives, and their leaders say their collective experience gives them the expertise they need to guide investees to the next level.

However, the exit potential of the strategy is unproven. Until investors can demonstrate the ability to develop a quality asset and achieve a liquidity event, buy-and-builds will not go mainstream in healthcare. Investors envisage various possible exit paths, from IPOs to trade sales to acquisitions by larger private equity players. But they admit the length of time required to grow assets to a suitable size presents a substantial risk.

"In these markets, our ability to take on significant debt as a core part of the thesis is not there, and if any of the assets starts to misfire in terms of growth it can be a big setback," says Everstone's Oberoi. "But the opportunity is that at the time of exit, you've created a platform that is really unique in terms of the management depth, scale, and quality, with systems and processes that are harmonized across all of your assets."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.