Indonesia infrastructure: Forging frameworks

Indonesia has set the stage for more private sector involvement in a government-dominated and desperately underdeveloped infrastructure space. A range of intangibles could impede the integration

The completion of the Trans-Java highway this year after a concerted development push has, for the first time, connected all the major cities of Indonesia's most populous island. The project was launched in the 1990s and had become a symbol of perennial investor concerns about bureaucracy and delays in the local infrastructure space. It is now being held up as proof that those days are over.

But as is the case with most issues in this complex jurisdiction, the milestone is muddled by its fair share of caveats. Most importantly, Trans-Java essentially represents an accomplishment of sheer political will and skyrocketing government infrastructure spending, with state-owned enterprises (SOE) taking most of the contracting deals and only negligible involvement of independent investors. Conspicuously, the ribbon-cutting comes in an election year.

The project has been the flagship of President Joko Widodo's administration-defining infrastructure agenda. As of the time of publication, citizens are heading to the polls as he faces an unexpectedly serious challenge for reelection. Investors are not particularly rattled about the implied instability, but their antennae are up. Infrastructure is the key to Indonesia's long-term economic health, and its latest episodes of politicization have included populist regulatory signals and dramatic budgeting decisions.

At the same time, Trans-Java's surge to the finish line, alongside other projects, has left many SOEs hobbled with debt, opening a door for the private sector to buy into de-risked assets that would normally be difficult to access.

"This week and last week have been very productive weeks for me, and I've seen some private developers that are very keen to develop new infrastructure projects from scratch," says Harold Tjiptadjaja, a managing director and CIO at Indonesia Infrastructure Finance (IIF). "One of them is in the process of getting a license to construct a greenfield seaport, for example, which I've never heard of in the past from the private sector. On the SOE side, one company with about 18 concessions is offering to sell 11 to private sector buyers."

Filling the gap

In the past year, the clearest measuring rod for this slowly unfolding opportunity set has been the public-private partnership (PPP). Before 2018, eight PPPs had been tendered in total, but none had reached completion. As of 2018, at least 15 PPPs were in various planning and development stages. At least six of these have reached financial close. Another two at the negotiation stage are expected to be announced in the coming weeks.

"PPPs get highlighted a lot at infrastructure conferences, but we didn't see any movement in terms of deal flow until two to three years ago," says Agung Wiryawan, a partner with PwC's infrastructure team in Jakarta. "I worked on a substantial number of PPPs last year, so the investor interest and regulatory framework is there, but uptake will some take time. The first wave is still going to be dominated by SOEs and local investors until the government can replicate its formula across different industries."

It is difficult to exaggerate the difficulty or importance of infrastructure investment and development in a country like Indonesia. With 17,000 mountainous islands separating a population of some 260 million across 2,700 miles east to west, the country faces unmatched challenges in economic uplift through geographic cohesion. Some $350 billion are said to be required for infrastructure through 2019, but less than a tenth of that is covered by the state budget in any given year. On an annual basis, the financing deficit is typically estimated in a range of $80-100 billion.

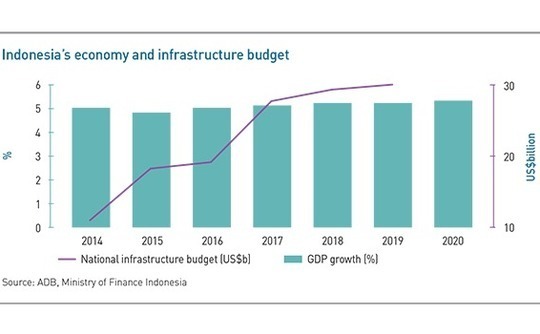

PPPs are expected to fill this gap, especially in areas with shorter payback periods and faster routes to revenue, including transportation and energy. The bulk of the sector's untapped potential, however, remains in basic services related to urbanization such as water and waste, which still often remain in desperate need of investment. Perhaps as a result, a 165% increase in government spending on infrastructure during 2014-2018 has inspired a positive but fairly static growth outlook in the macro.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) expects the economy to grow at 5.2% this year and 5.3% in 2020 on the back of strong domestic consumption and infrastructure development. The bank has contributed to this story through a string of investments, including partnership with Sarana Multi Infrastrukture, an SOE charged with catalyzing the implementation of PPPs. It expects the fast-tracking of a number of large national projects to stimulate private investment in the near term.

"The prioritization of infrastructure in Indonesia since 2014 has been instrumental in creating a larger momentum towards strengthening institutions and processes related to infrastructure development as well as infra financing both in the public and private sector and also in terms of PPPs," say Winfried Wicklein, country director for Indonesia for ADB. "This has set the scene and created a momentum for further infra development. It has addressed gaps that have been a major constraint to investment."

Private equity participation nevertheless remains sporadic. Energy has been the most active area for the asset class, with the likes of the International Finance Corporation backing Aneka Gas Industri and Saratoga Capital investing in oil producer Medco Energi. But the energy opportunity appears to be under medium-term pressure, with international investors continuing to shy away from fossil fuels as the country prioritizes traditional thermal power.

Some 58 greenfield coal plants are set to come online in the period to 2027, more than doubling coal capacity. This comes as the government has lowered its forecasts for electricity demand over the next 10 years by 22 gigawatts, enough to power for 15.4 million homes. Meanwhile, natural limitations have kept sweeping renewable energy plans in check. Equis Funds Group offered a notable exception with the launch of $500 million Indonesian renewables program in 2016.

Subtler headway is being realized by InfraCo Asia, a Singapore-based developer that enables private sector infrastructure investment by de-risking greenfield assets. The plan is to serve unmet demand in remote areas through small, nimble renewables projects, including a series of solar installations with diesel backup.

"In terms of new energy generation capacity, the government has toned back some very ambitious plans, but there's still a lot of need because you have to think of Indonesia as a continent, not a country," says Allard Nooy, CEO of InfraCo Asia. "There are millions of people without 24-7 power on thousands of outlying islands where expensive mini-grids rely on largely imported diesel. We've identified 10-plus locations in those areas for hybrid renewables with 24-7 backup, and we're building the first project on an equity-only basis."

Open door

The key advantages of the power sector are rules that allow 100% foreign ownership and the adoption of a US dollar-denominated tariff system, which has encouraged international banks to finance projects. Many other segments of interest to private investors, including transportation, require investment in rupiah and a consequent reliance on financing from local banks, which in turn tend to prefer engagement with SOEs.

The application of the energy model in other infrastructure domains is generally seen as a requirement for widespread private sector involvement. Traction on this front could be facilitated this year by a slowdown in government infrastructure spending. The annual growth rate for the sector's budget is set to fall from 6% in 2018 to 2.5% this year. But ultimately, the most enduring inhibitors will be cultural, not regulatory or budgetary.

The critical shortcoming in Indonesian infrastructure is insufficient participation by local capital alongside incoming foreign investors. This aggravates a sense of misalignment in PPPs whereby a disproportionate amount of risk is placed on the private partners. Even in the relatively progressive energy space, state off-taker Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) reveals the problem as more a matter of reliability in execution than red tape per se.

"Historically, PLN has been quite challenging to work with, insisting that they have a certain stake in a project, and when you agree, they say they need you to lend them the money because they actually don't have enough capital," says one foreign private equity investor in the country. "It's less of an issue now than it used to be, but it's still an issue, and it just makes it uneconomic when you're funding your partner essentially for free."

The question of consistency has arguably caused the most alarm in the toll roads segment, where new rules on tariffs and the classification of vehicle types are expected to cut into some investors' expected revenues. The government has promised to follow through with compensation measures, but concern remains that the whole episode equates to a bad first impression with much-needed foreign actors.

Much of the argument here is about trust. Investors ready to embrace the long timeframes of infrastructure must find ways to get comfortable with inevitable changes in government and policy, but they should not be obliged to suffer erratic twists in transparency. Finding practical solutions to this issue has proven to be a protracted process. The government-owned Indonesia Infrastructure Guarantee Fund, for example, has sought to offset any negative impacts on developers' profitability since 2009, but has realized only mixed results in improving overall sentiment.

"When you have signed an agreement, it doesn't mean it cannot be changed. There should be room for re-negotiation but on mutual benefit basis. Normally you should stick to certain agreed parameters, such as IRR," says IIF's Tjiptadjaja. "At the same time, it's a bigger risk if you change something for projects at the greenfield stage because you don't know the revenue patterns yet. At the end of the day, everyone realizes that political risk is one of the major risks in infrastructure."

Red tape rigors

The idea that political risk is sharper at the greenfield end of the spectrum could be problematic for the rural logistical build-outs favored by many private equity players in recent years. While Java has always been the economic nucleus of the country, rapid progress in internet connectivity, start-up ecosystem development and consumerism in outlying islands have altered the business-building narrative for investors.

This is especially relevant to PE-backed new-economy companies that have built massive, diversified businesses on pan-Indonesian strategies, namely Go-Jek, Grab, Tokopedia, Traveloka, and Bukalapak. In a country where logistics account for 20% of consumer operational costs, mobility, e-commerce, and delivery-based models arguably have more exposure to infrastructure issues than most.

The problem is that logistics-relevant infrastructure development in regional areas doesn't just benefit from social and commercial modernization trends – it is needed to keep them going. Indonesia's corporate sector, however, has proven relatively standoffish in terms of direct investment in this space, with the notable exception of Astra International, an industrial conglomerate with a dedicated infrastructure investment and operations division that invested $100 million in Go-Jek last month.

Still, the biggest threat to plans around lowering logistical costs through infrastructure remains the tendency for projects to be postponed. Land clearances, financing complications, and the time-consuming nature of PPP negotiations are the most common culprits. But from the international investor perspective, most of these factors boil down to a general lack of administrative competency.

"PLN was meant to launch a tender at our wind project for the past 18 months, but that process has still not kicked off," says one developer. "We've been working on this for almost three years and spent millions of dollars trying to get environmental surveys, get the option over the land, and go through wind tests. But we have no visibility and the government keeps delaying."

The regulatory recipe for creating an environment conducive to long-term planning horizons and investor security includes hedging mechanisms to address concerns about investing in rupiah, the replication of minimum offtake requirements found in the power sector in other urban utilities, and reduced foreign ownership hurdles. Last year, the government said it would open up various transportation segments to full foreign ownership. Airports, for example, are currently subject to 67% cap.

These moves have been welcomed and are indeed expected to make the sector more attractive, but few infrastructure investors need additional enticements in a market as underdeveloped as Indonesia. The deciding factor will be the culture around implementation because streamlined procedures are a good thing but playing by those rules in a predictable way is even better.

"The transparency on approvals processes, including setting a timeline, is the biggest setback for private investors in Indonesia," InfraCo Asia's Nooy says. "With PPPs, you need the right mindset on both sides of the table, and that's very much to do with capacity building on the public sector side. They're saying, we've got this single-window one-stop-shop for foreign direct investors, and the rest of the premise will roll off of that, but the reality is very different."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.