PE holding periods: The optics of exits

Should you take a 3x return today or wait for a potentially larger exit next year? For GPs, this decision is complicated by fears of a downturn, the timing of future fundraises, and conflicting LP feedback

Archer Capital took less than four months to close its fifth fund at A$1.5 billion (then $1.5 billion) in late 2011, easily surpassing the A$1.2 billion target. There was no shortage of demand, thanks to the Australian buyout firm delivering four exits over the preceding 12 months with an average return of 3.2x. It also committed A$600 million across four new investments.

Fast forward to April 2018 and Archer was forced to abandon plans to raise Fund VI. The launch had already been delayed by more than a year due to slower than expected deployment of the previous vehicle: the corpus was cut back by A$300 million in 2014 but the investment period still had to be extended twice as the search for deals continued, sources familiar with the situation say.

LPs were also concerned about exits. Of those four assets acquired at the tail end of Fund IV, three were still on the books as of autumn 2017. There was one trade sale to a Chinese strategic buyer late in the year, a few weeks after the first Fund V realization, but by then, time was already running out. Archer no longer had a critical mass of investor support for a new fundraise.

The team has since drawn up a blueprint for its future that does involve fresh capital, but Archer's struggles underline how easily a lack of realized returns can break a fundraise or at least throw it off course. Given mounting expectations of at best a valuation correction and at worst an economic downturn, it is an issue of which all managers are mindful.

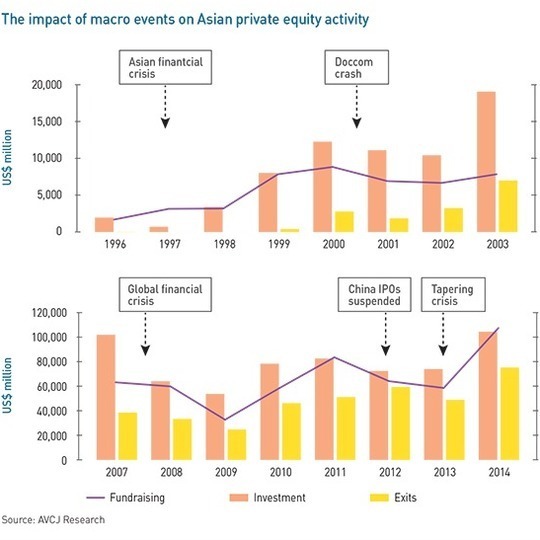

A common LP take on Asia is that the region's DPI (distributions to paid-in) doesn't match up to its TVPI (total value to paid-in), or to put it another way, strong growth at portfolio level doesn't necessarily result in more money returned to investors. A sharp macro shock would do little to confound this perception: holding periods would be pushed out as exits become difficult. No one wants to get caught on the wrong side of this, especially if they are or will soon be fundraising.

"There is always this need or temptation to sell something early because it has a disproportionate impact on IRR – you can't place all the risk on exiting after a certain number of years," says Katja Salovaara, a senior portfolio manager for private equity at Finland's Ilmarinen. "It's a pretty ingrained aspect of fund management, but with a potential downturn coming, the effect is exacerbated."

Lessons learned

Securing exits ahead of a fundraise is by no means a new phenomenon in Asia, especially for managers looking to graduate from Fund I to Fund II, where there is no multi-vintage track record. PAG Asia Capital closed its debut vehicle at $2.5 billion in September 2012 and within 18 months returned nearly $1 billion to LPs through three realizations.

None of them was spectacular, with gross multiples of 1.3x to 1.6x, according to a marketing document issued for the firm's second fundraise. But having exits on the board helped PAG closed that successor vehicle at $3.66 billion in late 2015 – beating the target of $3 billion – after just eight months in the market.

Speaking at the AVCJ Forum in 2013, Weijian Shan, the firm's CEO, noted that two-year holding periods were shorter than his historical average of four years. This was largely a response to a wider concern among LPs as to whether managers could return capital in what was then a challenging environment. "We have to increase the tempo because LPs are nervous," he said. "As a first-time fund you want to be able to return capital to LPs before going back to the market."

For many managers, the global financial crisis sharpened this awareness. Pacific Equity Partners (PEP) was among those blindsided. The GP had deployed one third of its fourth fund when Australia was hit by a triple whammy: a sharp retreat in consumer sentiment; some quickly imposed regulatory changes, which impacted businesses in different ways; and a strong negative swing in public equities.

Investment and exit activity seized up because no one could tell when and to what extent these variables would readjust. Private equity firms effectively missed an entire exit cycle because they were doing remedial work on portfolio companies while at the same time trade sale and IPO processes floundered. This left PEP heading into 2013 with Fund V in the market, while its predecessor vehicle was unharvested.

"A lot of people were under enormous pressure, so it was natural for LPs to be nervous about holding valuations and whether they might be too rich," observes Tim Sims, a co-founder and managing director at PEP. "When you see businesses aren't moving and holding values under pressure, you want to see realizations on these."

The multiples on well-managed funds of this vintage were respectable, but it took longer to achieve them. PEP's fundraise followed a similar trajectory, according to sources familiar with the situation. After a slow start, commitments flowed in once Fund IV began to deliver, culminating in a final close on Fund V in September 2015 at the A$2.1 billion hard cap. A total of A$1.2 billion was returned to LPs over the preceding 12 months, with A$900 million more coming shortly thereafter.

Portfolio diversification with a view to minimizing industry, currency or geographical risk is an approach Suvir Varma, a partner at Bain & Company, has seen employed by multiple private equity firms. Other strategies that have gained traction post-crisis include identifying a few operational initiatives that can really drive value in a company – with a view to pulling those levers as early as possible – and fully considering exit options on entry.

"Previously, most investors would get to year three or four and start asking whether they should sell to a strategic, and if so in which country, or look at the IPO markets," Varma explains. "Now, during due diligence, clients are saying, ‘Imagine we own this company, we are going to do A, B and C with it, and then who is to buy it from us in five years?'"

Delivering rapid results – from targeting bilateral deals so that improvement initiatives can be implemented before a transaction closes to starting vendor due diligence early to facilitate exits – has become part of the Navis Capital Partners toolkit. It is the result of lessons learned during the financial crisis, which the GP entered with a fifth fund that was almost fully invested but had delivered no realizations. Holding periods were extended and IRR suffered.

By moving quickly in areas like value creation, the Southeast Asia-focused GP looks to deliver a few quick exits early in a fund's life, so the portfolio isn't left high and dry by unforeseen macro or micro shocks. It sold MFS Technologies in early 2018 following a holding period of three years and three months. The money multiple was 3x. This was the first exit from Fund VII and it came a matter of months before the launch of Fund VIII.

"With the benefit of hindsight, we could have got more, but we would have been running with a fully naked portfolio, no realizations but mostly invested, for an extra period of time," Nick Bloy, a managing partner at Navis, told AVCJ last November. "I think that is unacceptable when we know we are late in the cycle and we are in a part of the world that is volatile."

Biding your time

Every placement agent AVCJ spoke to claims they routinely advise GP clients to hold off on fundraising if an exit is imminent but not yet certain. "In the planning stages we ask questions about when they expect to have additional exits and when the DPI will improve," says Vincent Ng, a partner at Atlantic Pacific Capital. "If the answer is we are a month away from an exit scenario, oftentimes we would recommend they wait until it happens or at least it is fairly certain."

Indeed, there are plenty of examples of how a timely realization can catalyze a fundraise. After failing to convince with its first fund, largely due to one sizeable write-off, Korea-based VIG Partners took around two years to raise a second vehicle. The final close of $350 million – well short of the $650 million target – came in early 2014, with minimal participation from foreign LPs, supposedly due to a lack of exits.

Fund III was a different story. The hard cap of $600 million was reached in early 2017 after less than a year in the market, with overseas investors accounting for more than 25% of the corpus. It helped that Fund I had been fully exited, but LPs were primarily looking at Fund II. VIG secured a first exit in February 2016, generating a 2.5x multiple from the sale of Burger King Korea. Combined with dividends from other investments, it took the DPI to 0.6. Fund III launched the following month.

"Fund I was not indicative of our capabilities, so LPs were focused on Fund II. The assets looked good, but investors weren't sure they were successfully exit-able," says Jason Shin, a managing partner at VIG. "When we sold Burger King, it helped give LPs the confidence that we were able to deliver on our trade sale exits."

In the absence of a reliable longer track record, VIG was essentially in a similar position to PAG: a manager that needed to show returns from its first fund in order to raise a second. When there is more to work with, the assessment criteria will be broader. LPs review the performance of different vintage portfolios across multiple years, checking the correlation between what a private equity firm said it would deliver and the actual results.

In this context, a lack of distributions from the most recent fund doesn't necessarily rule out a re-up – the GP could have deployed its capital within two years, enough time for investments to demonstrate potential though not enough for realizations – but LPs like to see something. Ilmarinen's Salovaara notes that if an LP re-ups on the back of zero returns, it could be doubling its exposure to an individual PE firm. This only happens with "a high conviction manager."

Eric Marchand, an investment director at Unigestion, recently went through this process with a portfolio GP. The existing fund was into year four, performance was not yet in-line with initial return expectations, and there was no DPI. A re-up was therefore not forthcoming. It could have been different had the manager agreed to delay the launch until after a first realization planned later this year. But this was overpowered by a competing urge to raise money while the macroeconomic conditions remained favorable.

"My advice to most GPs is if you are set for an exit that will create a bit of momentum, pre-market the fund as this deal is getting done," Marchand says. "Time is money. If I'm paying a management fee and you are flying around the world raising money, you are taking your eye off the ball. I don't like hearing from the placement agent that a manager is struggling to close a fund because that means they are visiting people like me, not looking after the businesses I am invested in."

The notion of securing exits for the sake of smooth fundraise, as opposed to harvesting when the crop is highest, does not sit easily with some industry participants. VIG's Shin suggests that managers who swap a solid return now for a potentially stellar one in a year's time, purely to support a fundraise, are "shooting themselves in the foot." Existing LPs could accuse the GP of acting contrary to their interests, while prospective backers might be put off by what they see as a cynical ploy.

But this raises the question as to what constitutes an acceptable trade-off. Would an investor forgo a 2.5x return today for the chance of getting 4x in two years? Or how about 3x today instead of a possible 6x in four years?

There is no consensus view. One GP makes the case to AVCJ that the timing of an exit is based on the interplay between the rate at which value is being created and the certainty of a downturn. As a downturn is never a certain outcome, if the value-add story is compelling enough the logical choice is to hold. Another manager advocates the opposite approach: there will always be black swan events in Asia, whether macro or micro in origin, so a windfall today at an acceptable multiple is preferable.

Bigger picture

Perspectives can be just as polarized at the LP level. While the likes of fund-of-funds, which need ongoing distributions, often call for immediate exits to lock in gains, an endowment or foundation that prioritizes long-term gains might advocate staying invested. Alternatively, a third group of LPs might push for realizations from the fund but offer to back a new vehicle that acquires a plumb asset with a view to continuing to ride the upside.

In this way, some see the dilemma as indicative of flaws in the traditional private equity model. For Unigestion's Marchand, the certainty of an immediate exit doesn't necessarily translate into better overall performance. Perhaps a manager's time and effort would be most productively spent realizing more value from a proven asset rather than trying to recreate the success story with investments that are less familiar and certain.

"You take on a whole new level of risk versus a situation where you may be watering down the percentage return but achieving a strong multiple with much more certainty," he says. "The latter risk-reward is more compelling, but that's unfortunately not how PE works. After two-and-a-half years, you have some people breathing down your neck saying get out or I won't give you any more capital."

Equally, the dynamics of fundraising, fund structures and fees could incentivize firms to push out the holding period on investments that are not home runs. LPs might become irritated with persistent offenders, but provided strong headline numbers are sustained, they are likely to be forgiving.

Entering year three of its current fund and with the launch date for the successor vehicle is approaching, a GP opts to sell the strongest portfolio company and realize a 2.5x return despite the prospect of 4x two years down the line. At the same time, management fees are based on net invested capital. The GP, therefore, chooses to sit on two weaker investments for an additional couple of years, turning 1.5x into 1.7x, even though the impact on overall performance is limited.

"The whole fundraising cycle – and the optics around fundraising and how distributions dovetail with that – can distort a GP's thinking around the timing of exits," observes Wen Tan, co-head of Asia private equity at Aberdeen Standard Investments. "But there's nothing you can do about that."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.