Indonesia PE: The long game

Indonesia is an attractive market for private equity investors thanks to its strong macro fundamentals, but sourcing large-cap deals remains a protracted process as family owners look for partners they can trust

Siloam Hospitals, then Indonesia's largest private healthcare player with about a dozen hospitals, was supposed to sell a minority stake to a PE firm at a valuation of 25x EBITDA in 2012. When no one was willing to be that bold, the owner – the Riady family’s Lippo Group – opted for an IPO. Three years after the listing, Siloam finally got a PE investor as CVC Capital Partners bought a 15% interest in the company at a valuation of around IDR12 trillion. As of mid-April, the company had 33 hospitals and a market capitalization of IDR13.66 trillion.

“We all knew it was going to be CVC,” says one investor with a pan-regional GP. “I got a call from the family, but the only private equity investor James Riady feels comfortable with is CVC. Thank God we didn’t waste the time.”

Of the pan-regional PE firms, CVC has been the most prolific in Indonesia. It started with Matahari Department Store in 2010, a majority acquisition from Lippo Group, and followed up with minority-joint-control investments in Lippo-owned cable TV provider Link Net and Siloam. The GP entered into similar arrangements with personal care products manufacturer Softex Indonesia and retailer Map Aktif Adiperkasa.

Given most large Indonesian conglomerates are well capitalized and resistant to private equity entreaties, an established relationship with the seller can provide a valuable leg-up – if the advantage is used properly.

“The five investments we’ve done in Indonesia have been with two groups – soon to be six investments and three groups,” says Andy Purwohardono, head of Indonesia at CVC. “The industries are diverse, but every company is the clear number one player in its market. Sometimes the opportunity comes not at once, but once you have built a relationship – understanding the seller’s needs and objectives, showing them how we can add value – so we become not just a financial investor but a trusted partner.”

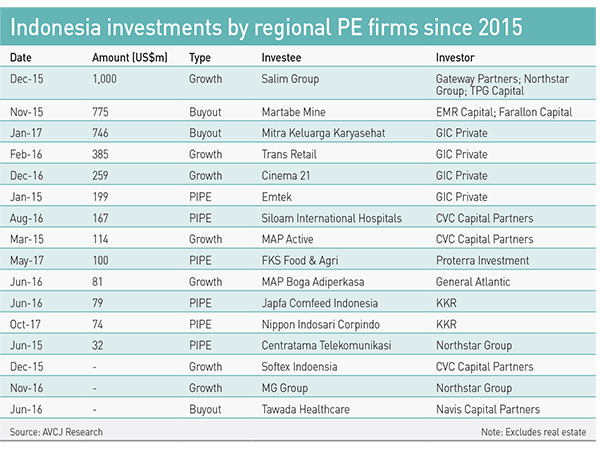

Limited supply

In the last three years, private equity investment in the country reached $4.53 billion, according to AVCJ Research. Transactions of $100 million or more accounted for 85% of the capital deployed, where investment size was disclosed, but this came from only 10 of the approximately 40 deals completed. During this period, CVC has made three investments, two of which were above $100 million. Meanwhile, each of GIC Private’s four commitments topped $100 million, and neither of KKR’s two deals crossed this threshold.

One of the other sizeable transactions was EMR Capital and Farallon Capital’s acquisition of Martabe Mine in 2015. David East, a partner and head of transaction services for KPMG, notes that very big deals usually fall under energy and natural resources or financial services, which are challenging for private equity due to remit restrictions and local regulations. On top of that, these deals involve multiple due diligence processes and advisors, with fees running to $10 million or more.

“If a large group is up for sale often, private equity investors might not want the whole thing and that means a carve-out or an asset deal, which are complicated to execute,” East adds. “Private equity has only been here post-global financial crisis – apart from one landmark transaction in 2008 – and their strategies often mirror those of strategic players. They start small scale and get a foothold rather than attack some huge juggernaut. If you stuff the first one, it will be your last, and larger deals are subject to greater risk on a range of fronts.”

Then there is the long cultivation period for many deals. Several investment professionals observe it takes years to go from initial contact with a family group to making a proposition, and then to closing a transaction. Obstacles include the family being reluctant to take money from a financial sponsor or wanting to maintain a high level of privacy, as well as valuations: if a company is growing rapidly, there might be a preference for high priced debt over giving up equity. But trust is arguably the key factor.

For example, Proterra Investment’s $100 million commitment to FKS Group’s food and agriculture platform last year was facilitated by the CFO and one of the directors having previously worked for Cargill. Proterra was formally a captive investment unit of the agribusiness giant and it had actually tried to recruit the CFO has a senior advisor prior to her joining FKS Food & Agri in 2016. The CEO also recognized that the GP understood his business.

“A lot of investors didn’t know what to do with FKS,” says Tai Lin, a managing director with Proterra. “It is involved in originating, transporting, warehousing and selling soft commodities from foreign countries to Indonesia, and then there are a lot of processing assets. It’s a volatile business and they aren’t easy to understand in Indonesia. We ended up being the first outside investor and right after that everyone was knocking on the door. The company has since raised more than $400 million from banks and strategic investors.”

Understanding the needs of the target can result in private equity investors coming up with innovative deal structures. When Northstar Group made a $1 billion investment in Salim Group in 2015 alongside TPG Capital and Gateway Partners, it was essentially helping the conglomerate build up capital to support an M&A push. However, the transaction was debt rather than equity-based.

The financing was secured against shares in two Salim entities: First Pacific, which has stakes in Philippine Long Distance Telephone, Indofood, and Goodman Fielder, as well as infrastructure and resources holdings; and Indomaret, Indonesia’s largest convenience store operator. The latter asset is the most significant. Northstar previously invested in Alfamart, the number two convenience store business, and was confident that Indomaret could also go public.

“Everyone knew there could be a deal and various parties pitched them, but most solutions did not fit their objective,” says Choon Hong Tan, co-CIO at Northstar. “We have known Salim Group for a long time and we’ve had touchpoints with them in multiple situations and this gave us some insight into how they think about valuations and the structure of the transaction. Even then, execution took over a year.”

KKR had to be similarly flexible when buying a 10.4% interest in Japfa Comfeed in 2016. The private equity firm purchased shares in two listed equities, taking the unusual step of eschewing downside protection. However, Jaka Prasetya, KKR’s head of Indonesia, notes that the structural complexity was driven by Japfa requiring financing at the Indonesian level and the Singapore holding company level, with old and new shares transacted. Other potential investors arguably passed on the deal because they only wanted to invest at the top level.

Avoid the process

What understanding and flexibility allow PE firms to do is avoid formal intermediation. Approaches vary in this regard. FKS did appoint a financial advisor who prepared some materials with a view to doing some soft marketing before Proterra came in through its own connections. Families that aren’t solely motivated price might also require third-party assistance because they have not previously dealt with private equity investors. But in most situations origination is informal.

“Unlike markets like Singapore where eight out of 10 deals PE investors compete in a process to the end, in Indonesia this happens in two or three out of 10 deals,” says Sunata Tjiterosampurno, Northstar’s other CIO. “In the other ones, we receive inquiries and work with founders and families on solutions. There might be a process at the start, but depending on the situation, we might turn it into more of a bilateral discussion. We have been around for 12 years, so we might have a head start.”

For pan-regional firms that don’t have so much longevity in the market, the onus is on hiring local talent. KPMG’s East observes that one real estate-focused investor can’t hire enough people to do the deals it is sourcing because it has some well-connected Indonesians who build up a sizeable pipeline, while others struggle to close even one transaction.

Meanwhile, KKR’s Prasetya, though based in Singapore, was active in Indonesia as a banker and a corporate executive before establishing his own credit fund. CVC does have a local presence and Purwohardono spent 20 years in banking, latterly as Indonesia head of Morgan Stanley, before joining the firm. Sigit Prasetya, now CVC’s Asia managing partner, is also a Morgan Stanley alumnus. As such, they not only have advised family groups on transactions, but they have a strong grasp of the minutiae of Indonesia deals.

“A lot of foreign funds don’t know Indonesia, aren’t comfortable with it, and they are highly legalistic,” says Purwohardono. “Once they’ve finished the due diligence and the legal wording comes into play, the deal could fall apart because there is no trust. The legal wording always focuses on the worst-case scenarios – things that often have a 0.01% chance of happening. We think more carefully about the actual probability of something happening.”

Part of the strategy for PE executives in Indonesia is therefore cultivating ties with the largest family groups. This applies to local players as well as pan-regional firms. Saratoga Capital was established in 1998 and operated like a family office before transitioning to managing third party capital on a formal basis in the mid-2000s. According to Devin Wirawan, a partner with the firm, there wasn’t much competition in the early days and a lot of deals originated from inbound inquiries. Now, with ample liquidity in the system, Saratoga must be more proactive, conducting top-down due diligence before approaching attractive companies.

“You need to maintain contact on a regular basis, it could be small things like if it’s the festive season you reach out to them,” Wirawan says of keeping tabs on family groups. “Or we ask them for dinner and ask if we can help them through our networks. When they do need funding, we hope our number will be on their speed dial list.”

Saratoga also appointed the former country head of Unilever as a partner three years ago to support its deal-sourcing efforts in consumer-facing industries. His team helped in the buyout of hospital operator Famon Awal Bros Sedaya in 2016. This underlines the importance of being able to demonstrate value creation credentials when dealing with Indonesian companies.

KKR spent three to four years talking to the sponsors of Indonesian bakery business Nippon Indosari Corpindo before paying $74 million for a minority stake last year. The company was backed by Salim Group, a Japanese corporate, and the founding family and they focused on how the private equity firm could drive operational improvements. With Japfa Comfeed, KKR highlighted its dairy investments in China because the parent company has dairy interests in China and Indonesia.

“The word relationship is somewhat overused – everyone claims to know everyone, although perhaps they do. We’ve found that, if you work well with a family and really provide solutions for their company, they will recommend you to other businesses and families, and that’s how a network really grows,” says Prasetya. “It’s of course important to be in a room face-to-face with these families, but once you’re in there, the value-add that you bring above and beyond capital alone is important to differentiate yourself from their other relationships.”

Patience required

Succession should make deal-sourcing easier in Indonesia as founders who are hypersensitive to the political and social issues tied to a sale are replaced by overseas-educated sons. The younger generation is generally more open-minded about working with PE and appreciative of the benefits third-party investors can offer. That said, they are still unlikely to countenance full buyouts and their greater sophistication means they will compare notes with other corporates and conduct more due diligence.

“I want to say it will become easier, but I would have said the same five years ago,” says Proterra’s Lin. “The economy is so consolidated. You have a few families running sectors and they are big, they have too much money, so why do they need more? It’s a question of what you bring to the table in addition to money.”

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.