Australia distress: The luxury of time

Two pieces of legislation – one enacted and the other pending – are expected to facilitate corporate restructuring in Australia. It remains to be seen how turnaround investors take advantage of this

Arrium's demise was a drawn-out affair. The Australian minerals giant achieved a market capitalization of A$7 billion ($5.5 billion) in mid-2008 as net profit hit a record highs of A$245 million. But the global financial crisis and a collapse in steel prices strangled the business. By 2015, Arrium was sitting on an annual loss of A$1.92 billion and more than A$2 billion in outstanding debt. Its stock had lost 96% in value.

With the company teetering on the brink, GSO Capital Partners came in with a A$1.3 billion recapitalization plan, but this was rejected by the banks. The business went into administration in April 2016. It took 18 months for creditors to receive their first dividend payment – at A$0.10 on the dollar – following the sale of the company.

The odds were always against Arrium, but several restructuring experts question whether a less damaging denouement might have been secured were the directors not under a particular kind of pressure: they could have been held personally liable for debt incurred if the company continued trading while insolvent. Without this burden weighing on them, would the board have felt confident enough to hold on a bit longer and consider other options?

The introduction of a safe harbor regime in Australia removes this legal liability provided directors are taking a course of action that is likely to lead to a better outcome than the appointment of an administrator. The legislation – and changes to ipso facto rules that prevent termination of contracts for reason of insolvency – is seen as part of a wider push to create an environment that is friendlier to restructuring, and potentially to turnaround investors.

"There've been situations where there was an opportunity to restructure but directors weren't prepared to take the risk, so they just put companies into insolvency, leading to massive value destruction. Now directors can have greater runway to come up with a solution," says Carl Gunther, a restructuring partner with KPMG. "Some people say it's the biggest change since the introduction of the voluntary administration regime in the 1990s. I would agree with them."

Shift in mindset

Opinion is mixed as the significance of safe harbor specifically, but the consensus among local investors and advisors is that various forces are nibbling away at what is described as a harsh insolvency regime by international standards. As a bellwether of industry sentiment, the Insolvency Practitioners Association of Australia was renamed the Australian Restructuring, Insolvency & Turnaround Association (ARITA) a few years ago.

Two key structural factors play into this. First, the market is maturing, helped by more secondary trading of debt and a rising number of liquidity providers, including foreign special situations investors. "The market is becoming more institutional and looking to solve problems in a commercial way," says Ilfryn Carstairs, partner and co-CIO at Värde Partners. "It is no longer just a case of liquidate or not. There is more focus on out-of-company or consensual restructuring."

Second, Australian banks are seen as increasingly willing to give borrowers time to work through distressed situations rather than enforce on the debt. This is a regulatory and a reputational issue. Australia formed a royal commission into misconduct in banking last year following a string of scandals over the past decade, including accusations of customer exploitation. They do not want to be associated with situations in which bankruptcies cost jobs, even if they are not wholly to blame.

"Political inquiries and TV investigations alleging incontrovertible conduct by banks have created opportunities around distressed situations," says Said Jahani, a partner and head of financial advisory at Grant Thornton Australia. "We have been involved in situations where investors have approached banks about situations and the banks are open to these solutions because it avoids the nastiness of a public bankruptcy."

A classic hypothetical example is a company that has become overleveraged to the point that it owes A$20 million but the business is only worth A$15 million. It requires A$5 million in new capital to effect a restructuring but its bank won't lend any more. An investor offers to buy the debt position for A$10 million and provide capital for a restructuring. The bank takes a haircut but it likely emerges with larger proceeds than if it had brought in a liquidator and there is less of the hassle.

These situations, where the debt can be several hundred million dollars in size, are said to be attracting special situations investors ranging from international groups like Oaktree Capital and PAG Asia Capital to local players Allegro Funds and Anchorage Capital Partners. It is contributing to a drop-off in creditor-led insolvency.

"The availability of capital to restructure from an equity point of view is advantageous for the banks as they seek a non-enforcement way of preserving their assets. Everyone is a winner: companies get restructured earlier, banks realize their positions earlier and value will not be lost," says Adrian Loader, a co-founder and managing director at Allegro.

Macro to micro

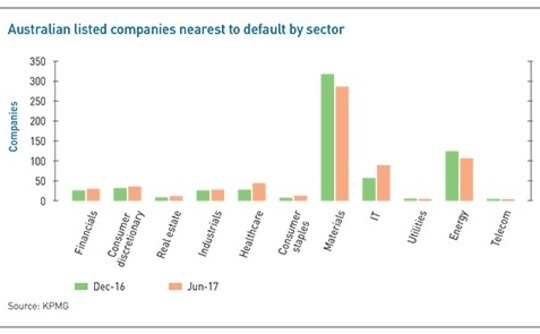

However, Australia's distressed space is subject to cyclical as well as structural forces. Deal flow tends to be driven by economy-wide downturns, sector-led downturns, and mismanagement. The first is non-existent at present, while the second is not as pronounced as in recent years. The latest edition of KPMG's twice-yearly tracking report of potential defaults of listed companies indicates improving corporate health. Materials and energy are still the main areas of distress activity.

"In a growing or robust market, distress situations may still manifest through a number of factors, poor management decisions, inappropriate capital structures, a bad acquisition as examples. They are not necessarily correlated to the market in general, although a robust market can mask some of these issues," says Byron Beath, a managing director at Oaktree Capital. At present, he sees situations in retail and mining services.

The low-interest rate environment that underpins the current buoyancy cannot persist indefinitely. But the way in which investors take advantage of debtor-led opportunities as they emerge – and the extent to which they see safe harbor and ipso facto contributing to this – depends on where they operate in the market.

"The more operational players are doing more retail businesses where they can add value with their turnaround and operational knowledge," says Paul Apathy, a restructuring partner with Herbert Smith Freehills. "The offshore funds tend to be more of a financial play. They are looking for larger capital structures where they can put their balance sheet to work."

At the other end of the scale, for small companies with a sole director who is also employed in the business, legal liability over trading under insolvency is likely to be a non-issue: they need to keep trading to put food on the table. Rather, the key constituency is the middle market, comprised of larger privately-owned businesses and smaller listed companies. Some directors are already calling in advisors to find out more about their options and obligations.

The full extent to which businesses take advantage of the legislative change is unlikely to be known because there is no requirement for public disclosure, even for listed entities. Most advisors say there is a lot of talk about safe harbor but so far relatively little action. James Marshall, a partner with Ashurst, notes that, in order to protect directors, the new regulation requires a third-party advisor to give a professional opinion supporting a company's decision to enter safe harbor because it is likely to lead to a better outcome than an immediate winding up. There is a general wariness about doing this given the system hasn't been tested.

"There is an independent review of safe harbor in two years' time and I expect there will be some case law towards the end of that period to test a number of issues that are a bit gray," adds Stewart McCallum, a partner at Ferrier Hodgson. "The impact of safe harbor will be significant, but I don't expect it to be immediate."

Certainty of treatment

Much the same can be said of the contractual safeguards offered by the ipso facto reforms, which don't come into effect until the beginning of July of this year and only apply to agreements signed from that date onwards. As one industry player remarks, this means the wait for a meaningful impact "could be three years, could be 10 years, could be never," as existing contracts are rolled over instead of new ones signed, but it still might be hugely significant for private equity.

There are already protections that prevent landlords of business from walking away solely due to insolvency on the part of the renting company. However, once the administration period ends, and with liquidation about to begin, they are free to terminate – and they have been known to demand sweeteners to forgo this option. Ipso facto rules state that termination cannot happen if there has been no payment default, swinging the power away from landlords.

This also applies to commercial contracts in general, for which there are no preexisting protections and often contain termination for convenience clauses. "For companies that have extensive customer contracts with a lot of goodwill wrapped up in that, ipso facto coming into effect is another tool in their kitbag to use insolvency. Seeking to preserve goodwill in contracts by selectively retaining certain high-value contracts will be beneficial to restructure the business," says KPMG's Gunther.

Loader cites this uncertainty over contracts as one reason why Allegro has typically been reluctant to target distressed soft asset businesses in administration like retail. "There have been no more than three successful retail buyouts out of insolvency in Australia because it's so hard," he says. "Every single lease is terminated, the licensing agreement with the branding company is over, all the employment contracts are over. You have to renegotiate everything."

Ipso facto is expected to give turnaround investors a much more secure starting point. For example, if an insolvent company has 100 stores, of which only half are profitable, an incoming investor would have the ability to cancel leases on the unprofitable establishments and from there work towards a restructuring.

Loader is wary about overstating the potentially transformative nature of ipso facto, or safe harbor for that matter. He cites the relatively benign market conditions at present and the broader consideration that the industry needs to adjust to the new legislation by adding the necessary skill sets – much as when voluntary administration came in.

Put simply, change will happen at the margins. There are already signs of an evolution within the industry as the "corporate undertakers" typically associated with formal appointments of receivers build up their restructuring and turnaround advisory capabilities. Nevertheless, the Big Four accounting firms, with their large client bases and established advisory relationships across different functions, are expected to be the major beneficiaries of this shift.

Curiously, for all the emphasis on restructuring, few practitioners expect there to be a material decrease in insolvency events. Rather, they will come as part of a more thought-out process. A company could enter safe harbor in the knowledge that three new contracts will come in within four weeks and then enter administration – knowing that by holding on creditors will get A$0.40 on the dollar rather than A$0.10.

"If you can get in there before the business enters bankruptcy it could be an easier turnaround because you don't have to put back together the thousand pieces of glass that have shattered across the floor," says Grant Thornton's Jahani. "But you need to have a plan that will ultimately deliver a better return to creditors and shareholders. Step eight of a 10-step plan might be a formal bankruptcy process to deal with a certain issue."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.