Philippines PE: Growth potential

Philippines-focused private equity funds are young and unproven. The investment theses need to play out – ideally resulting in more deal flow for larger GPs – for the industry to come of age

When Honorio Poblador joined Morgan Stanley Private Equity Asia in 1999 part of his brief was to make investments in the Philippines. The closest he came was with media group ABS-CBN Corporation. Poblador drew up a term sheet for a $15 million deal that would increase the company's public float with a view to boosting its trading volume and valuation. But the controlling Lopez family ended up deciding that they didn't want to proceed.

More than a decade on from that disappointment, ABS-CBN finally did business with private equity. Capital International invested PHP2.5 billion (then $60 million) in 2013 to support expansion of the company's digital television offering.

To Poblador, now a managing partner at local GP Navegar, this development illustrates how the scale of the investment opportunity has grown. Navegar, which closed the first-ever dedicated Philippines fund in 2014, regularly writes checks in the $15 million range where Morgan Stanley found such slim pickings. He hopes these companies can become attractive targets for pan-regional players, justifying the investment theses of local managers and sustaining the country's PE industry.

"The biggest challenge in the Philippines is there aren't many companies capable of absorbing $100 million or more that are controlled by people who need private equity," says Poblador. "But over time, the companies we are investing in today – businesses that weren't previously on the radar – will be able to absorb $100 million. When this happens there will be more opportunities to invest."

Two extremes

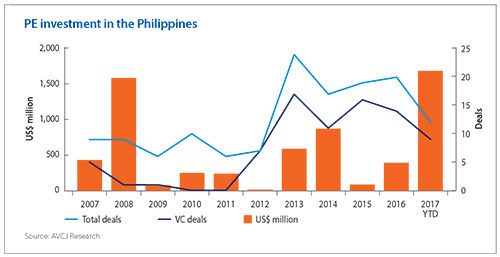

Private equity investment in the Philippines stands at $1.69 billion so far in 2017, more than any full-year total on record. Almost all this capital can be traced back to two deals: GIC Private and Macquarie Infrastructure & Real Assets' $1.28 billion investment in renewable power producer Energy Development Corp. and Partners Group's acquisition of business process outsourcing (BPO) company SPi Global for $330 million, which provided an exit for CVC Capital Partners.

Previous years have followed a similar theme, with the odd large-ticket transaction pushing up the annual total. Overall deal count has grown, but this is largely due to the emergence of venture capital. Non-VC investments still number in the single digits, according to AVCJ Research.

Plenty of private markets deals likely slip beneath the radar. Yet it remains curious to many why the Philippines – which exhibits consistently robust economic growth and has a 100 million population that is both young and increasingly consumption-oriented – isn't generating enough interest and activity to warrant the existence of more domestic private equity firms.

"One of my first observations arriving in Asia was, ‘Why are there so few local institutional fund managers in the Philippines and Indonesia?'" says Ralph Keitel, principal investment officer in the International Finance Corporation's (IFC) PE and investment funds department. "Looking at the size of the populations, their GDP growth and GDP per capita numbers, I am still surprised there are only 3-4 country-focused GPs in Indonesia, just two in the Philippines, and three in Thailand."

The second Philippines-focused manager emerged last year with the formation of Sierra Madre. Its founders are Martin Lorenzo, a serial entrepreneur who previously ran food producer Del Monte Pacific and restaurant chain Pancake House; Danny Lizares, previously country manager for Aureos Capital and The Abraaj Group, whose successful investments include Pancake House; and Alasdair Thomson, formerly of Apax Partners in Europe.

The firm is targeting $120 million for its first fund and reached an initial close of approximately $50 million in March. IFC is an investor, having already backed Navegar's $119 million debut vehicle, which was launched with the support of Swedish alternative asset manager Brummer & Partners.

Both GPs operate in the $5-20 million space – although Navegar has committed as much as $40 million to a single deal with co-investment – where non-local private equity firms seldom go. Pan-regional managers will travel to the Philippines to look at potential investments of $100 million or more, and some Southeast Asia-focused players are willing to go lower, but the smaller the ticket size the harder it becomes to justify the transaction costs.

"We feel you can best put together a diversified portfolio of investments where the pool is deepest. Companies with at least $1 million in EBITDA start to be of investable scale, as at that point they have demonstrable profitability and the operating levers to drive growth. There are about 8,000 companies of that size or greater," Sierra Madre's Thomson says. "We've proven historically we can build a business around that investment thesis, and there is strong deal flow so we can be picky about what we do."

Local rivals

Even in the absence of other institutional private equity managers, target companies still have alternative sources of capital. A founder might begin by bootstrapping his business, raise capital from friends and family, and then go to the banks, pledging property assets in return for financing. Once those avenues are tapped out, private capital providers beckon.

As in other Southeast Asian markets, a paucity of GPs with institutional backers is compensated by a relatively robust non-institutional market. "With such an abundance of liquidity in these markets, perhaps institutional private equity in the traditional sense is not needed as much as one might expect at this stage of the evolution of the PE industry," says IFC's Keitel. "It seems good founders can always find a family or a high net worth individual (HNWI) to help them get off the ground."

Non-institutional is a catch-all for several different kinds of investor. There are groups that aspire to raise funds from traditional LPs and are working on a deal-by-deal basis – alongside transaction advisory mandates – in order to build up a track record. Angeon Advisors fits this profile, raising capital as required from a combination of HNWIs and offshore financial investors.

A second category comprises professional investors that so far have not tried to tap the institutional market, instead relying on their own resources and contributions from friends and family to finance transactions. Argosy is a readily cited example; one of its senior partners is Alfonso Yuchengco III, a member of the family behind local conglomerate Yuchengco Group, which controls Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation (RCBC) among other assets. Another is Bonifacio Capital, which is run by Jay Singson, who also previously invested in Del Monte.

"There are a few groups like this, it's a popular format," says Gerald Baldivia, a managing director at Angeon. "They are happy with the fact that they are not large enough to be on the radar. I'm not sure if they could be described as real private equity houses; they are more like clubs of friends and family."

Competition from family conglomerates is scarce. Navegar lost out on a pharmacy chain to Ayala Group, but this was one of multiple acquisitions towards the creation of a healthcare vertical, so its willingness to write a small check should be seen in a broader context. While these family groups do exert enormous influence in their core sectors, for smaller GPs the strategy is to invest in businesses that serve these giants or operate in adjacent areas to them. It makes exits easier to envisage.

"We see there is interest in our portfolio from many of the regional PE firms because they have appetite for the Philippines and by the time we are done building them these investments are a decent bite size for regional players," says Anders Stendebakken, a managing director at Brummer. "The level of M&A in the Philippines has also increased in the last five years. The whole ecosystem has grown and many of the local conglomerates now have established business development and M&A functions."

Navegar's Poblador identifies consumer, healthcare and logistics as areas of interest for the conglomerates. In this sense, the objectives of these companies are not so different from the GPs that might end up selling assets to them: everyone wants to leverage a consumer economy that is expected to double in size over the next 15 years. Infrastructure is the other missing piece, but those deals are beyond the reach of Navegar and Sierra Madre.

A more meaningful, though peripatetic, source of competition comes when HNWIs – who may or may not be linked to the big families – pursue deals on their personal accounts, whether the target is a car dealership, a restaurant chain, or a drugstore business. However, traditional private equity investors are keen to point out that their proposition is very different from the HNWIs.

"If you take money from a HNWI you are pretty much giving up control and there is no timeline on how long that relationship is going to last," says Sierra Madre's Thomson. "We want to invest in situations where the entrepreneur is interested in driving the business forward and we can support them on that journey. Being a long-term but non-permanent investor, and being clear on where we add value in building the business are two key differentiators. "

To this end, it is incumbent on the private equity firm to prove that its capital is genuinely differentiated. This is true of all markets, but perhaps especially in economies like the Philippines where the asset class is not necessarily well understood and founders are reluctant to give up any equity – let alone a majority position – to third party investors.

"A lot of these smaller family-run companies are interesting, but introducing a stranger into the fold is always a challenge. It's not easy to do a deal, it is very relationship driven," says Reginaldo Anthony B. Cariaso, senior managing director and co-head of investment banking, BPI Capital Corporation. "There is a lot of liquidity in the market, so what makes a local PE firm stand out?"

IFC's Keitel adds that any minority investor that is unable to demonstrate strong value-add risks being seen by founders as nothing more than replacement capital to a bank loan – and so these founders will tweak the numbers to make sure they only get a bank return.

A common theme between the two private equity firms IFC has backed in the Philippines is diversity of background. The Sierra Madre founders comprise an entrepreneur and two established PE investors, one with a domestic track record and the other with international experience. At Navegar, Poblador brings private equity knowhow while his co-founder, Javier Infante, spent years in senior roles at Telus International, a BPO company with a substantial presence in the Philippines.

The basic idea is to combine an ability to speak the language of local founders and entrepreneurs with a history of managing third-party money for institutions and investing it through multiple cycles. If LPs need to be sold on the market opportunity, the viability of GP's strategy, and the qualities of the team in order to be comfortable committing to a fund, the third box is arguably the hardest to tick with regard to the Philippines.

"The really tough thing is putting together a team – there are so few people with transaction experience who want to be based here," says Thomson of Sierra Madre. "On a global scale, how many Filipinos (or foreigners with deep country knowledge) are there with senior-level PE experience? I can think of 7-8 and six of us are here already."

Prove your worth

Brummer was willing to make the leap in part because of its unique approach to frontier economies. The firm launched the first Bangladesh-focused PE fund based on a desire to move early into markets with a strong macroeconomic outlook over a 5-10 year period. The Philippines exhibited similar characteristics. Stendebakken says the firm was attracted by the large consumption share of GDP and services-driven export profile at a time when exports from the rest of Asia were slowing.

Brummer's view has not changed: it believes the Philippines has outperformed and is keen to invest more. Other LPs will want to see more evidence of investment theses playing out.

Several industry participants draw comparisons between Pancake House, which grew from about 60 outlets when Aureos invested to more than 300 on exit, and Bistro Group, a casual dining chain in Navegar's portfolio that currently operates around 50 restaurants. If the latter could replicate the former's success it would go a long way to proving that local GPs can deliver growth and scale. However, Poblador cautions that any shift in mindset will take time.

"Many LPs look at the Philippines and see the potential – but when was this country ever the darling of the investment community? You can't change that perception overnight," he says. "Why would people put money into a Philippines fund over a Southeast Asia fund? Industries are not as developed, the managers are unknown quantities. There are too many hoops they have to go through to get approval."

SIDEBAR: Intermittent visitors

On launching its third fund in 2015, Creador announced plans to broaden its horizons. In addition to the existing markets of Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and India, the firm would consider deals in the Philippines and Sri Lanka. A team member was deployed to Manila and instructed to meet companies, with a managing director flying in every few weeks to assess the opportunities.

This arrangement was shelved after one year due to difficulties finding high-quality assets. "We've done 15 deals over 15 years in financial services," says Creador CEO Brahmal Vasudevan, referring to investments completed in his previous role at ChrysCapital as well as with Creador. "But we couldn't find a single asset in the Philippines that was growth and had the right return-on-equity profile."

The firm is still looking for deals, but on a fly in-fly out basis. Vasudevan believes the initial forays into the Philippines are most likely to come through helping portfolio companies from elsewhere in Southeast Asia expand into the country.

Creador is not alone in taking this approach. For the large pan-regional investors, fly in-fly-out is the only logical way of addressing the Philippines given deals requiring equity commitments of $100 million or more are thin on the ground. AVCJ Research has records of just eight deals in the last six years that crossed that threshold.

"If you are a regional fund of $1 billion, trying to invest at least $50 million per deal, few companies in the Philippines can absorb that level of capital and all of them have access to the local banking market," says Alasdair Thomson, a partner at local GP Sierra Madre. "Investing at that size, you can't support a local team because you're doing one deal every three years."

Even among the wholly or primarily Southeast Asia-focused GPs – firms that write checks of $50 million and up – the country is not a priority. Navis Capital Partners, for example, sends someone in every few months to assess the market. Meanwhile, Southern Capital is not tracking the Philippines at all, saying there is more than enough to keep it occupied in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia.

The most active private equity investor in recent years has been GIC Private. The sovereign wealth fund deployed more than $550 million across three Philippines-based deals in 2014, and it has followed up with two more investments in the last 18 months, teaming up with Century Pacific Group in a $323 million acquisition of the local master franchise for Shakey's Pizza and joining a consortium that committed $1.28 billion to renewable power producer Energy Development Corp.

"We met GIC in 2013 when they sent a senior and large delegation to the Philippines," recalls Honorio Poblador, a managing partner at Navegar, another local GP. "They said they classified the Philippines as uninvestable and were there to find out whether it should remain on that list. Then they did five deals in a row. The speed at which they decided and deployed capital surprised us."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.