PE and Islamic finance: Underlying themes

Encouraging trends in population, social mobility, commodities, technology, and governance standards are converging on Islamic finance. PE plays a small role with strong upside in Asia

Japan is not the first place most investors think of when the conversation turns to Islamic finance. But two recent private equity deals – a $100 million commitment by SBI Holdings to an Indonesian fishing project and a $3.6 million growth round for Japanese energy tech start-up Microwave Chemical provided by Inspire PNB Partners – have created a promising development narrative for this niche area.

The transactions bring two evolutionary steps into focus: the notion that non-Islamic countries are beginning to participate more ambitiously in shariah-compliant investment and the emergence of new playbooks for penetrating the breadth of PE-VC potential in the space.

Both deals are also notable for illustrating a gradual shift in Islamic cash flows away from the Middle East. SBI's Islamic fund is reportedly backed by the Islamic Development Bank but otherwise largely an instrument of the Brunei government. Inspire PNB's shariah-compliant Ethical Fund, meanwhile, is supported almost exclusively by Japanese banks with no Islamic agenda.

Emerging markets investor Inspire Corporation and PNB Asset Management, a Japanese subsidiary of Malaysia's Permodalan Nasional, launched the fund as a springboard for local companies looking to tap Southeast Asian markets. While that strategic vision is familiar, the Ethical Fund is arguably the only vehicle of its kind embracing it from an Islamic angle.

"There are so many good companies in regional areas of Japan that don't have the resources to expand their businesses overseas, especially in ASEAN and Islamic countries where they need a partner to bridge the gap between cultures," says Ryosuke Takatsuki, president and CEO of Inspire PNB. "They understand that those markets are getting bigger in the mid to long term, and we want to help them get in touch."

The maturing process that these deals imply about the Islamic finance industry presents an opportunity for private equity to reconcile a growing disconnect: although almost a quarter of the world's population is Muslim, less than 1% of financial assets are shariah-compliant. PE is well placed to step into this gap, but it will take a combination of education, legal maneuvering and philosophical reflection.

Ground rules

Conceptually, Islamic banking and finance is defined by ethics. In practice, it is most commonly viewed as a risk profile. While these perspectives may suggest a discord between social responsibility and the dispassionate assessment of investment merit, Islamic overlap with the broader wealth management industry is generally considered harmonious.

The cornerstone of Islamic finance is a prohibition on collecting returns through interest rates, which is considered a form of usury. Earnings must be connected to an underlying transaction with as small of a debt component as possible and a risk sharing mechanism that outlines agreed divisions of profit and loss.

Deals that involve tangible assets or direct social impact are usually preferred, with some of the most popular sectors including healthcare, infrastructure, manufacturing, food, car leasing and education. Notable embargoes encompass industries related to pork, alcohol, gambling, pornography and prostitution.

Historically, these investment criteria have caused little friction with the already conservative tendencies of the conventional finance industry, especially in Asia. For example, only one of Macau's approximately 25 banks is said to accept gambling deposits from the territory's myriad casinos. Las Vegas, by contrast, has proven to be an open hunting ground for the likes of Deutsche Bank and The Blackstone Group.

Asian opportunity is also supported by the region's economic immaturity, which lends itself to less debt-dependent deal-making. According to Malaysia's Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB), the total value of Islamic financial assets in Asia increased 19% to $425.5 billion during the four years to 2016. This represents a global market share of 22%, compared to less than 4% for Europe and North America combined.

In Asia, the industry dates back to the 1990s, when Malaysia began angling for a competitive edge over Indonesia by promoting a substantial Islamic bond industry. After the global financial crisis, the country was able to consolidate its regional leadership by diversifying into fringe areas of the industry such as managed funds.

The value of Malaysia's Islamic fund assets grew by around 24% per year across the six years to 2015 and amounted to $14.2 billion by last year. Total Islamic fund assets for Asia as a whole – which is home to most of the world's Muslims – came to $20 billion in 2016, accounting for 35% of the global market, versus 45% for the Middle East.

Regional strength in managed funds, however, remains muted by the limited scope of the overall industry. IFSB estimates the global Islamic money pile at $1.9 trillion – a massive reserve but one that nevertheless struggles for attention against the $250 trillion mountain of conventional wealth. Indeed, Islamic banking cracks the 20% mark of total banking activity in only one out of five majority-Muslim countries.

The International Shariah Research Academy for Islamic Finance has tracked a decline in the number of Islamic funds from 1,181 at year-end 2014 to 1,053 in the fourth quarter of 2015. During this time, Islamic assets under management globally eroded 4% to $58 million.

"Islamic banking and finance has lost a lot of its luster due to the downturn of economies and instability in the Middle East and Arab world," says Lord Edwin Hitti, president of the Arab Chamber of Commerce & Industry (ACCI) in Hong Kong. "There are fewer funds specializing in Islamic banking and finance, and since interest rates have been so low, people don't see the advantage vis-à-vis conventional."

Periodic transactional wins are gradually alleviating the perception issues causing Islamic capital flows to be subjected to a more intense scrutiny. But the niche nature of the industry, especially within private equity, has made a meaningful reversal of sentiment difficult to achieve. Thomson Reuters and the Malaysia International Islamic Financial Centre estimate that alternatives represent only 0.2% of global assets under management.

"There's a lot of money that is sitting idle and being labeled as having suspicious origins," adds Hitti. "The minute you say Islam on any capital, red flags go up, and that's slamming the brakes on investment coming out of the Middle East. That is why a lot of Middle Eastern countries have been investing in themselves, building all these towers in Qatar and Dubai and so on – but nobody talks about that."

Organizations such as ACCI and its Amwal credit union have not had success establishing Asian sources of Islamic capital independent of Middle Eastern financial institutions, high net worth individuals and sovereigns. As a result, Asian Islamic fundraising has remained burdened by the correlation between Middle Eastern economics and the sluggish oil prices of recent years.

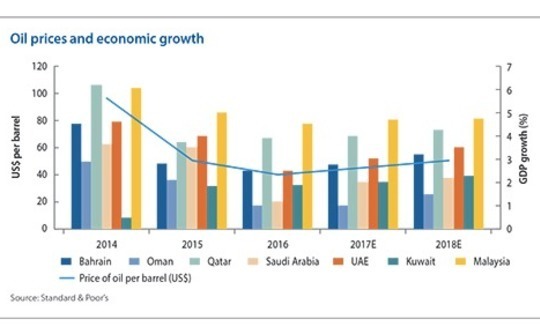

According to Standard & Poor's, growth in Islamic financial markets was reduced by almost 2.5x between 2010 and 2016. Oil prices fell about 40% during this period, in inflation adjusted dollars. The weak performance for Islamic economies is predicted to continue across the next two years, given a stagnant outlook for oil prices of around $45-50 a barrel.

Slowing markets, however, are not necessarily shrinking markets, and Islamic LPs are increasingly looking for geographic diversification as their ultimate source of wealth expands. Muslim population growth rates are projected to double the global average at around 70%, reaching 4.8 billion people by 2050 and establishing Islam as the world's most widespread religion.

The PE angle

Private equity firms targeting this phenomenon are naturally geared toward developing markets, with patient, venture-oriented profiles that focus on social impact investments.

Navis Capital Partners has floated a number of sidecar and standalone Islamic funds in Malaysia since the late 1990s – its most recent flagship fund closed at $1.5 billion with a parallel shariah-compliant vehicle backed by a mix of Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian LPs. Although the shariah component of this effort represents less than 10% of the fund, it highlights persistent progress for Islamic PE uptake in the region.

"The Islamic private equity market is certainly evolving but organically and at a gradual pace," says Rik Muilwijk, a partner and general counsel at Navis. "With each of our funds, the allocation to the Islamic parallel fund increases, but as a manager you have to accept that educating shariah concerned investors as to the benefits of the asset class takes time; credibility, expertise and experience in Islamic investing are key considerations for potential investors."

For Islamic LPs, integrating PE into their portfolios will largely be a matter of confirming the viability of the various legal frameworks that make shariah-compliance possible in an asset class traditionally associated with leverage. Since the learning curve in this area can be trying, it may be difficult for conventional GPs to justify taking up a shariah program with only 1-2% of overall LP backing coming from Islamic investors.

The main consideration in fund structuring is to avoid cash flows that contravene the basic profit and risk sharing principles of shariah law as well as the prohibitions on leverage, interest and restricted industries. The most common method is the use of feeder vehicles, whereby a side letter gives LPs a grace period of a few weeks to decide if they want to opt out of a particular investment.

The key issue with feeders is they may be viewed as an inherent contradiction since they ultimately require the LP to be an indirect investor in a non-compliant fund. Many GPs therefore establish parallel vehicles that comply with decisions made by external shariah investment committees.

"In the whole scheme of structuring to accommodate LP interests, bringing in a shariah investor is not particularly onerous, especially if there's a fair bit of money coming in," says Andrew Ostrognai, a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton. "GPs very much feel that it's worth it because these investors are a recognized asset class for portfolio balancing."

Effective approaches

Structuring the most effective legal framework depends to some extent on subtle and personal differentiators between LPs, and will accordingly require an element of customization. Some Islamic committees and investors are willing to back companies that earn as much as 5% of their revenue from non-shariah businesses.

"My understanding is that there are practical gradations in the ways in which one interprets the laws and how broadly the application of the laws goes," says Ostrognai. "The whole spectrum of interpretations can generally be accommodated, but GPs shouldn't go in thinking that just because they have a shariah vehicle, it will address all investors' needs. One size will not fit all."

While it suggests a certain flexibility, individual considerations of Islamic compliance can also cause mechanical problems. When LPs opt out, or are automatically excluded from investment activity, it creates a need to catch up mathematically by increasing exposure to the fund's other transactions. Especially strict investors can nix up to 30% of deal flow, and may therefore not have enough time within the investment period of the fund to draw even.

Complications of this sort will need to be eradicated if private equity as an industry is going to expand its slight role in Islamic finance. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most practical way forward in this regard will eschew sophisticated new legal products in favor of a basic alignment of interests.

"It's important for conventional fund managers to identify the potential of investments and assets to be able to pass a shariah committee," says Bernard Yap, a Malaysia-based tax partner for EY. "In Malaysia, committees are starting to look at ESG [environmental, social and governance] principles adopted in the West when they're making assessments from a shariah perspective. If you can see those principles in target entities, I think it's easier to convince a shariah committee to approve them and bring them into an equity fund."

Yap flags a number of tax implications for conventional funds, including additional steps in the management of capital gains and stamp duties. There may also be a need to ensure that remunerations can be tied back to performance improvements and a clear contribution from the asset manager. GPs in such instances have to supply regular reports on their direct involvement in portfolio companies to confirm that the investments are not thriving simply due to external factors.

As with the structural basics of shariah sidecars, accounting issues are best mitigated in the curating of the deal pipeline. "When people get into Islamic finance and parallel funds, they think it's a technical discussion and tend to focus on the mechanics quite a bit, but if you take a more holistic view, it's more about the nature of the underlying investments," says Navis' Muilwijk. "Once your investment objectives fit seamlessly with Islamic principles, it is relatively easy to incorporate Islamic private equity into your mainstream investing."

The most inherently compatible strategies will encourage community risk sharing with a strong focus on participation and uplift at the local level. As such, crowdfunding in particular represents a unique opportunity to bring Islamic finance closer to private sector investors.

Ethis Ventures, a Singapore-based crowdfunding firm focused on Islamic-compliant deal structuring services, uses proxy ownership schemes to provide bridge funding to small businesses and property developers. It identifies education about its operational processes as one of the biggest hurdles, even with a largely Muslim and internet-savvy investor base.

"How you invest with an Islamic platform or a regular platform is pretty much the same, but explaining the details of the contract is a challenge," says Ahmad Sabree, business and shariah development consultant for the firm's real estate and infrastructure arm, EthisCrowd. "A lot of people have heard of crowdfunding, but there's still that anxiety of trying something for the first time."

Although Malaysia government data attributes only 0.2% of socially responsible investment to Asia, the region's rapid advances in venture and hyper-local alternative financing could represent a distinct opening for Islamic capital. Ethis, like Inspire PNB, secures the majority of its investment from Asia.

Further advantages in Asia include a lack of hostility towards the Arab world compared to Europe and the US as well as a unique edge in skill sourcing for Islamic scholars who make up the relevant investment committees. Despite the Middle East's longer history of academia, Kula Lumpur-based INCEIF claims to be the world's only university dedicated to Islamic finance.

The economic rise of Islamic populations, both in Asia and globally, is expected to further these advantages on a number of fronts. The convergence of trends in ethical investing, ESG rigor and Muslim demographics will intersect with the development of new financing avenues such as crowdfunding and the emergence of a globally independent Asian venture ecosystem. At the same time, the push toward modernity, especially in the massive Islamic nations of Southeast Asia, will drive increased interest across the hemisphere.

"Since we started Inspire PNB in 2014, businesses in Japan have learned more about Islamic investment," Takatsuki says. "Many Japanese investors are tracking our fund, and if it's successful, they will be looking to take a position in future Islamic funds."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.