Indonesia resources: Storms and blue sky

Indonesia’s resources sector has proven a socially and politically tumultuous investment environment in recent years. GPs are monitoring the headline issues and maintaining long-term confidence

When Singapore's Pierfront Capital committed $25 million to Indonesian miner Merdeka Copper Gold last September, it demonstrated the resilience of the domestic resources sector's appeal – even in the face of severe challenges to investor sentiment. The show of confidence, however, belies a consistent wariness for what is arguably private equity's toughest theater of operation.

At the company level, the investment was notable for confirming Merkeda's full reputational recovery after a two-year dispute at its flagship Tujuh Bukit mine that ended in 2014. At that time, Saratoga Capital and Provident Capital helped broker a rescue buyout by Kendall Court, effectively smothering an all-too common spot fire in negotiating Indonesian ownership rights.

Merdeka also received its latest backing – in the form of a term loan facility – during the most confidence-rattling Indonesian mining controversy in recent memory. As of January this year, a rising tide of resource nationalism has hardened long-developing government moves to seize control of Freeport-McMoran's gigantic Grasberg copper-gold mine in the province of Papua, triggering emotional public demonstrations and economically important operational disruptions.

"Investors, especially foreign investors, are assessing the Freeport situation at this time to see if the agreements that have been agreed to in the past will be honored by all stakeholders," says Kay Mock, a founding partner at Saratoga. "It's a tricky situation because changes in regulations do happen. The rules introduced by the government indicate that they would like to see local parties own the majority of significant concessions – and I think this is probably something that is going to continue."

Unpredictable beast

The notion that Indonesia is a more difficult and bureaucratically cumbersome investment environment than otherwise similar developing economies is based on impressions of the market's unpredictability. This factor has been evident in the counterintuitive timing of the country's latest attempt to rewrite foreign ownership rules for commodities projects.

Most emerging resource markets began pressing nationalistic agendas as the commodities boom crested a series of price highs from 2011 to 2013. Indonesia, by contrast, didn't fire up efforts to wrest control of resources from foreign operators until 2014 when commodity values had already begun to sink.

The narrative suggests that the country's resource politics are comparatively less connected to economic cycles in the sector. Since the election of President Joko Widodo in mid-2014, a number of regulatory changes have eroded investor sentiment despite the administration's pro-business reputation. It is claimed that Widodo's lack of resources experience has emboldened the government's old power brokers in the sector to push policies that are not necessarily in line with national interests.

A steady string of disputes at Grasberg during the past few years has given this backdrop some of its most dramatic flashpoints. Most recently, the government has sought to take 51% control of the operation within two years under revised foreign ownership rules. At the same time, export rights have been curtailed with new requirements for on-site processing and local investor participation. Freeport has responded by reducing Grasberg output to as low as 10% of capacity and laying off some 2,100 workers.

The overall effect has been a reduced footprint of Western-headquartered conglomerates. In the past year, BHP Billiton and Newmont Mining have been pressured to sell minerals projects to local buyers. In energy, Chevron has decided to pull out of the country in several years, and Total has been refused a gas contract extension despite its Japanese partner being allowed to continue operating. Interestingly, Japan and Korea-based companies are rarely targeted by government-linked takeovers.

For regional private equity players, the implied opportunity lies in picking up the best assets that strategics are leaving behind. EMR Capital, for example, entered Indonesia in 2015 with a consortium of co-investors including Farallon Capital Management by purchasing the Martabe gold mine from Hong Kong and Australia-based G-Resources in a deal worth $775 million.

"We expect that some of the headline items in the press should be contained to those situations rather than seen as a proxy for what's happening in general," says Jason Chang, managing director and CEO at EMR. "We continue to be attracted to Indonesia, not just for the quality of the projects, but also because we expect the government will continue to be open to foreign investment. In terms of consistency, there may be rule changes, but these are generally well foreshadowed and applied prospectively."

The government's tendency to revise resource sector rules has nevertheless become a common concern among interested players. The export ban on unprocessed ores legislated in early 2014 is the highest profile of these changes. It requires base metal exporters to build smelters that can cost in excess of $1 billion and guzzle enough electricity to necessitate an additional on-site power plant.

National copper output fell 24.5% year-on-year during 2014 to 366,000 metric tons as nickel production dropped 55% to 215,000 tons. Earlier this year, the government reacted by softening the ban's enforcement parameters but ultimately aggravating a general sense that regulations are subject to constant revision. Companies with exposure to commodities outside the purview of the ban – such as Martabe and Merdeka – have fared relatively well.

"Pierfront invested in Merdeka Copper Gold with a degree of confidence that the domestic upgrading regulations would not impact a gold-focused operation that produces gold and silver dore bars on site," says Andrew Starkey, director for Pierfront. "As such, a detailed assessment of the circumstances surrounding the export ban was not required."

Merdeka has remained unscathed simply because its copper resources are deposited at deeper levels than the gold – a commodity that is not impacted by the ban. Operations are expected to begin exploiting copper reserves in about five years. "It's something we would need to deal with, but we still have some time to figure it out," explains Saratoga's Mock.

In addition to gold, coal has performed relatively well in the past year due to increased demand from China and firmer pricing. The challenge for regional private equity players looking to benefit from the momentum is entering an environment already dominated by domestic capital. But even outside of coal, the chances of identifying acquisition targets suitable to private equity and private credit investors remain limited to a thin field of viable options.

"Within the coal industry, there is a wide range of investment opportunities. However, in the precious and non-precious metal sector, there are only a small number of assets of a suitable quality and scale that are either in production or could be in production over the short to medium time horizon," adds Pierfront's Starkey.

Cost considerations

Private investment opportunities in the oil and gas space may also come under pressure as a result of regulatory changes that are expected to make it harder to develop more speculative deep-water blocks. Earlier this year, the government signaled an overhaul of the cost recovery regime for oil and gas production sharing contracts (PSC) – transitioning the industry to a system based on gross split production sharing contracts, whereby the required capital and risk is to be fully borne by the contractor.

"The feedback we have received is that for blocks that will require high capital expenditure, the new gross split regime is unlikely to be attractive relative to the previous regime," says Ben McQuhae, a partner at Jones Day, specializing in energy and natural resources. "In some cases, the new fiscal terms may simply be a deal breaker for would-be investors. But the uncertainty created may well add value to some companies that hold an old-form PSC license with full cost recovery benefits."

Theoretically, the change represents a streamlined approvals system, but it will result in new costs being eligible for tax deduction, which could in turn result in offsetting delays. The increased risk burden on operators, meanwhile, means that technically difficult early-stage projects are likely to suffer from underinvestment as existing licenses expire and fall under the terms of the new regime.

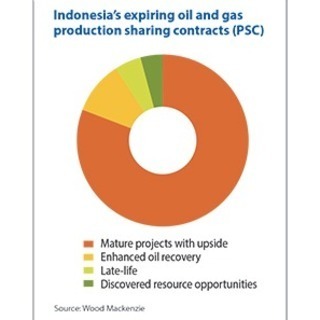

According to Wood Mackenzie, Indonesia's expiring PSCs were worth about $10 billion as of November last year but are predominantly composed of mature or late-life tenements. This scenario implies an expanded role for state oil company Pertamina, which has already been muscling in on properties held by the likes of Chevron.

"For the big oil and gas majors in Indonesia, the one thing that keeps them up at night is the fact that the rules keep changing," says Mark Thornton, managing director of Indonesia Private Equity Consultants. "You can't pull the trigger on spending billions of dollars if you don't know within the next 5-10 years if you're going to end up losing control of the project."

Regulatory uncertainties are further intensified by decentralization of government oversight. Since the constitutional reforms of the early 2000s, Indonesian decision-making authority has gradually evolved from a top-down Jakarta-centered system to a more complicated power hierarchy involving multiple layers of local stakeholders, typically with incompatible interests. Although such bureaucracy is far from unexpected in developing markets, its comparatively recent arrival in Indonesia has created new problems for industries with particularly long timeframes such as resources.

In a political sense, regional empowerment has been a successful initiative since it preserved the integrity of a fragmented archipelago nation as it transitioned out of the centralized military leadership of the three-decade Suharto era. However, it has also resulted in an inexperienced provincial authority structure with unrealistic expectations for foreign resource players and a susceptibility to conflicts of interest.

Political capital

With the arrival of the Widodo government, a clear vision of economic expansion has been put in place, but it is not yet evident that it can be consistently executed or sustained past the political cycle. The overarching concern is that the struggle to effectively combine policy vision, execution and sustainability has created an environment that is now less accommodating to foreign resources investors than previous administrations. Indeed, consultancies serving foreign investors in the country have charted a distinct decline in resources related activity.

"Wherever investors are looking is where we tend to operate, and from the perspective of our client profile, it's not an extractives market anymore – it's a consumer and infrastructure market," says Dane Chamorro, a senior partner at Control Risk in Singapore. "This is not a place you want to be for extractives at the moment. That might change, but right now, Indonesia just doesn't have the policy elements that foreign investors need to be successful in that sector."

The natural counterpoint to this view is that growth in one area doesn't necessarily mean that other areas are shrinking. The explosion of interest in consumer plays based on domestic demographics has changed the ratios in Indonesia's economic pie chart, but it hasn't nullified the intrinsic value of the export-oriented resources sector.

PE investors pursuing resource strategies with a higher risk-return are expected to continue finding opportunities in locally-connected companies. This opening may be especially inviting to distress specialists, given the fact that many of the Indonesian companies that formed in the heat of the latest commodities boom have taken on more debt than they can handle. Much of this debt is in US dollar terms, which could ripen the M&A market if US interest rates go up.

"A challenging market does not mean that it is closed for foreign investors, although they certainly have to manage risks carefully to operate in Indonesia's resources sector," says Adimas Nurahmatsyah, senior associate for investigations and disputes in Kroll's Indonesian team. "The challenge does not necessarily come from public scrutiny or local civil society, but from facing political and business actors who, on occasion, exploit local sentiment for their own gain. Therefore the most important thing for foreign companies to do is to understand who they are dealing with, who are their counterparts, and what are their expectations."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.