Indonesia VC: Corporate kingpins

The corporates and family groups that dominate Indonesia’s economy are becoming increasingly active in the VC space. To independent GPs, they are more friend than foe, but agendas and approaches vary

Not long after Kejora Ventures launched its debut fund in 2013, co-founders Sebastian Togelang and Andy Zain were approached by the CEO of Indosat Ooredoo, one of Indonesia's leading telecom providers: He wanted to create an incubator to support domestic start-ups. Indosat would put up the money; would Kejora be willing to run it in return for shares in the portfolio companies?

Four years on, the incubator – known as Ideabox – has backed 16 businesses, each of which received up to $500,000 and was taken through a 120-day accelerator program. Ideabox represents a successful partnership between a VC firm and a local corporate, but it isn't the only one to emerge under the Kejora banner.

Barito Pacific Group, a conglomerate with interests in petrochemicals, timber and palm oil, was one of four family-owned business groups that together committed $12 million to Fund I. It has re-upped for Kejora's second fund, which has an overall target of $80 million. The number of family office and corporate LPs is growing in tandem with the fund size, but as much for strategic as economic reasons.

"These families have established connections to key decision-makers and people in government over many years. It is good to have them as partners, particularly when they already have media or retail assets and can offer some strategic value," says Togelang. "These partnerships are one of the ways we want to help start-ups grow faster in Southeast Asia, but at the same time we wanted to be independent. Fortunately we have several families Investors to maintain this neutrality.

These groups – acting through family offices as well as through the companies they own – have become a significant presence in Indonesian venture capital, making commitments to funds, establishing VC units, and making balance sheet investments in start-ups. Rather than squeezing out independent GPs, they are seen as a complementary force in a nascent ecosystem, but it is imperative that structures maintain a balance between different interests.

Zero to hero

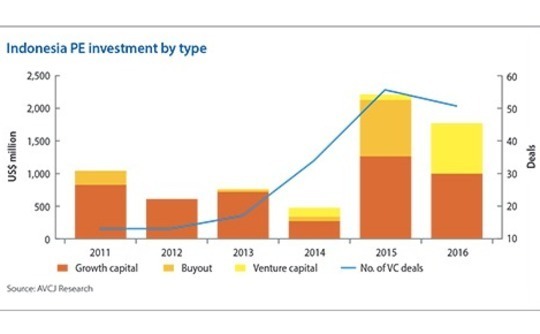

Venture capital has gone from zero profile to high profile in the space of six years: there were barely a dozen investments of negligible aggregate size – in most cases the dollar value was not disclosed – in 2011; in each of the last two years, the deal count has surpassed 50, with an unprecedented $781 million committed in 2016, most of it to ride hailing and delivery player Go-Jek.

The seeds of domestic corporate VC were sown at the start of this period. Djarum Group is regarded as the pioneer, having established domestic incubator Merah Putih and early-stage investor GDP Venture – which is led by Martin Hartono, son of Djarum Group's head – in 2010. GDP's acquisitions include social networking site Kaskus and e-commerce platform Blibli.

Among the telecom and media specialists, Indosat Ooredoo formed an investment unit around the time it launched the incubator with Kejora. Telkom Indonesia has a similar setup, with captive VC unit MDI and incubator Indigo, and Emtek Group has established itself as an aggressive balance sheet investor. Several banks, including Bank Mandiri and Bank Central Asia, have also set up captive investment divisions.

Activity now stretches well beyond Indonesia's largest companies. Mark Thornton, managing director of Indonesia Private Equity Consultants and also Jakarta-based CIO of a non-Indonesian family office, notes that he often comes across groups looking to enter the space, with little thought to strategy. The classic example would be an overseas-educated third-generation family member who has no interest in the family business and is allocated capital for investment.

"He comes back and sets up a venture business and runs some family money. It doesn't work very well and it doesn't really matter. Other groups recognize they need to hire people to do it professionally," Thornton says. "But the people who do these roles tend not to last very long, especially if they want a mixed portfolio of listed and private investments. As soon as the listed investments struggle they are out of the door. Family offices often don't have the patience to see things through and the stomach for risk."

Although there is no shortage of family scions in venture capital, it doesn't follow that they are necessarily part of unsophisticated setups. As Khailee Ng, managing partner at 500 Startups, puts it: "You rarely see one family member running around with a check book. They build these businesses for learning and success, and this involves hiring outside professionals."

Venturra is a widely cited example of this. John Riady is the grandson of Lippo founder Mochtar Riady and said to be a competent technology investor in his own right. But he brought in Rudy Ramawy, formerly a director at Google Indonesia, to serve as managing partner of LDV; the pair were joined at Venturra by Rocket Internet alumnus Stefan Jung. Skystar Capital is also said to be run by a combination of professionals and members of its family affiliate, which also owns Kompas Gramedia Group.

Strategic rationale

For Kompas Gramedia, a media conglomerate with interests spanning newspapers and magazines, book publishing, multimedia and hospitality, the motivation for participating in venture capital is clear: the company wants to get the inside track on technological developments that will redefine its core businesses and if possible use its existing assets to monetize them. The same can be said of telecom providers and financial institutions.

"The sector is changing and the bank recognized it could lose market share to financial technology companies. It wanted to stop losing customers, so the bank decided to establish a corporate VC to invest in these potentially disruptive areas," says Eddi Danusaputro, CIO of Mandiri Capital, which was established by Bank Mandiri last year. In addition to capital, portfolio companies get access to the bank's financial expertise and can test their products on a large network of merchants and customers.

Opinion is divided on whether the activities of investment units under the diversified family groups is more opportunistic than strategic. The launch of MatahariMall by Lippo would appear to fall into the latter category: the company saw how e-commerce was cannibalizing traditional retail, where it has a significant presence, and positioned MatahariMall to capture some of this business by offering an online-to-offline consumer experience.

"Many of these groups are investing in businesses that will become big in the future, and e-commerce is definitely an area in which they see disruption of their core businesses," says Adrian Li, co-founder of Convergence Ventures. "I don't think it is opportunistic and only happening because e-commerce is the flavor of the month. Look at any market in the world and e-commerce has taken market share from traditional retail, so these are defensive measures."

In other situations, it is harder to trace motivations back to a fear of disruption. Many of the leading conglomerates have substantial property businesses and a healthy start-up ecosystem is seen as a way to attract young professionals and expatriates to a new township, making apartments easier to sell. Any investment in an incubator or co-working space could therefore be considered a small marketing cost tied to a much larger project.

With this in mind, if there is likely to be any confusion over a captive investment unit's ultimate agenda, it is important that the group makes its position clear. "Especially in the early stages, they might need to make explain that they are operating as financial rather than strategic investors says Kejora's Togelang. "This means clarifying how some entrepreneurs or other minority investors can exit in the future and how they can work with other groups to scale further."

While some family groups insist on control, which is likely to be a deal-breaker for many entrepreneurs, the primary concern when bringing a corporate VC unit into a funding round as a minority investor are the strings attached. Is the investor insisting on exclusivity, which would prevent its peers from participating in future funding rounds? And would alignment with this group rule out partnerships with others? Danusaputro says these issues have led to Mandiri Capital missing out on deals.

Beyond that, an entrepreneur might be resistant towards particular groups. "People used to say, ‘Don't you just want to own us?' and it took a while for them to understand that we are a minority investor along the lines of a Western VC firm," Roderick Purwana, managing director at SMDV, told AVCJ earlier this year. "Even now, start-ups that are familiar with us have a very positive or negative view."

Pick your partner

For similar reasons, VC firms are wary of being perceived as too close to an individual family group. After closing their first fund at $150 million in 2015, the Venturra founders stressed that Lippo has no more influence over investment decisions than any other LP. Like Kejora, Convergence was careful to cast itself as a fully independent player, even though the majority of the capital in its $30 million debut vehicle comes from corporate and family office-type LPs.

Rather, the reliance on these investors is seen as characteristic of a market that has yet to deliver sufficient exits to attract fund-of-funds and endowments. Venture capital firms think about family groups in terms what works for each fund – the number and diversity of the participants, and how they can add value to the portfolio.

"Corporates have become more and more open to taking on LP positions in funds. What they've found is that by doing this they are able to get capital managed in a professional and independent vehicle and also get some of the insights into the industry offered by professional GPs," says Convergence's Li. "If you looked a few years back that wouldn't happen."

Indeed, feedback on the major corporate or family-backed venture capital investors is generally positive. Their enthusiasm is seen as beneficial to the ecosystem – it helps to have established local players expressing confidence in local start-ups – and they are useful source of co-investment capital when portfolio companies require follow-on funding. If their strategic resources can help these businesses scale faster as well, all the better.

Needless to say, not every group fits this profile. According to one industry participant with a more jaundiced view, many Indonesian families have accumulated wealth rapidly on the back of government contracts, concessions and cheap land deals. This hampers their ability to make long-term strategic plans. The danger is they see venture capital in the same way: a source of quick returns on investments that require minimal hands-on management.

More groups are expected to participate in the asset class, and their approaches will evolve over time, whether that means going direct or through LP commitments to funds. The large conglomerates in particular – given their significance to the Indonesian economy – will play a significant role in the development of the ecosystem, as VC-style investors in start-ups and as strategic buyers who facilitate exits for VCs.

Both Kejora's Togelang and Ng of 500 Startups talk about progress being dependent on a change in mindset, but with different objectives. Asked whether corporates and families could fill the country's Series B funding gap, Togelang says more will take part, but it will take time for them to get comfortable with the business models and the notion of minority ownership at lofty valuations. Ng, meanwhile, envisions venture capital as an agent of longer-term reform.

"If some of these families look at it with a longer horizon, say 30-50 years, any one of them could create a big shift in the way Indonesia will be," he explains. "What makes technology so exciting is the entrepreneurs have a bold vision. If the families come in with the same kind of boldness – as well as their resources, networks and access to talent – that could be very exciting. But it means approaching the sector with more deliberation and vision."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.