Fundraising and co-investment: Friends with benefits

Co-investment is becoming more sophisticated as managers sharpen fundraising strategies and respond to the needs of large investors. It points to an increasingly customized and complicated GP-LP relationship

The pursuit of cleaning and catering contractor Spotless Group by Pacific Equity Partners (PEP) took upwards of six months. The Australian company's board resisted a series of approaches by the PE firm until, under pressure from major shareholders, in April 2012 it endorsed a bid that valued the business at around A$1.1 billion (then $1 billion).

PEP did not act alone. While the bulk of the equity came from the firm's fourth fund, there were further commitments from a parallel co-investment vehicle and additional co-investment from the market. Spotless swiftly introduced a value creation plan intended to improve earnings. Non-core assets were offloaded, overheads were reduced and productivity improved, and the business was repositioned to better engage with customers. By the time it re-listed in May 2014, EBITDA was up 78%.

Investors had already taken out some cash via a refinancing and further proceeds came through a partial exit at IPO and then three block trades, the last of which was completed in August 2015. The investment generated a multiple of 2.4x and an IRR of 55%. PEP is hoping for more of the same in its fifth fund, which closed earlier this year. However, the way in which co-investors participate will be different.

The PE firm's previous three funds were two thirds core equity and one third supplemental, with the latter used as top-up capital for deals above a certain size. Both tranches charged carried interest of 20%, but while the management fee for the main fund was 2%, the supplemental vehicle took a 1% fee on drawn down capital only. Every LP in the main fund had pro rata exposure to the supplemental vehicle.

For Fund V, the dual tranche approach has been modified, with a select subset of prequalified LPs now able to participate in co-investment on a discretionary basis with zero fees.

"The previous model worked well for us, but it became clear there was increasing segmentation in the market between investors who valued co-investment greatly and those that were not as able to participate in it," says Tim Sims, managing director at PEP. "The pricing had also changed for co-investment, with the more sophisticated investors wanting to participate at no or low fee level."

Under the new model, PEP is still able to flex up from the classic Australian upper middle market deal to target businesses with enterprise values of A$1 billion. But it functions most effectively with pre-qualified co-investors that have the experience and resources to respond to opportunities within a set timeframe.

This increasingly customized approach to co-investment is not unique to PEP. Various industry participants say they are seeing a shift away from dedicated vehicles to bespoke arrangements. It is not only a reflection of the differing levels of importance LPs attach to co-investment but also, on a broader level, an acknowledgement that not all investors are created equal. In a competitive fundraising environment, groups that are willing to come in big and come in early have increasing scope to dictate their own terms.

Haves and have-nots

Private equity fundraising in Asia follows the 80-20 rule: 20% of managers have no problem attracting capital, their vehicles come in oversubscribed, and LPs are term takers rather than term setters; the remaining 80% find the going tougher, and flexibility in terms and conditions becomes a means of attracting LP commitments.

"With funds that have a normal fundraising track you can play around with the LPA [limited partnership agreement] and negotiate," adds Wen Tan, a partner at Aberdeen Asset Management. "The ones that say, ‘We are fundraising and we'll be closing in three months' time, let us know what number you want and you may or may not get it,' that is an entirely different dynamic."

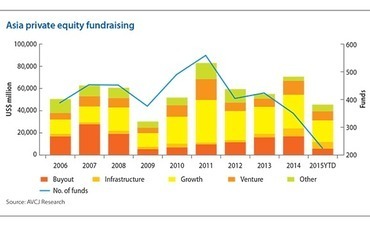

This state of affairs also contributes to an ongoing bifurcation in fund size. A total of $45.7 billion has been raised for Asia-focused private equity funds so far this year, tracking below the 2014 level but roughly on par with each of the two years before that. A consistent trend is that this capital is going to an ever smaller number of managers. A select few of these managers are raising ever larger funds.

"There has been a bit of a shakeout in the middle market," says Nicole Musicco, head of Asia Pacific at Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan (OTPP). "There are groups that hoped this time around they would be able to raise capital and they're having a tough time. And the bigger guys seem to be able to continue raising capital, assuming they have good track records."

Track record is generally the most important ingredient of a fundraise, but it is not the only one. Doug Coulter, partner at LGT Capital Partners, emphasizes the importance of a "narrative that hangs together" - a clear and compelling story that expresses the market opportunity and how a particular GP is positioned to capture it.

This corresponds to the experience of a manager who closed a fund earlier this year. The team's pitch was based on a differentiated story, a credible track record, and a strategy and skill sets that are relevant to the Asian PE landscape. For all the supporting documentation provided to aid due diligence, one LP had seven meetings but didn't commit, while another was happy enough to come in as the first investor after just one lunch, having got comfortable with the story and the dynamics of the team.

Comfort is key, particularly for US and European LPs with investment committees that do not necessarily have a strong grasp of Asia. Like many institutional investors, Andy Hayes, private equity investment officer at Oregon State Treasury, considers whether opportunities are additive to the portfolio in terms of diversification and returns, but there is also a somewhat holistic angle.

"It's a question of how they see us as partners," he explains. "Do we believe that if something goes wrong we can sit down with them and figure out how to go forward? That is something not all GPs in Asia understand but it is important to US LPs. It is all about trust and without that trust you don't even start."

Getting comfortable

In this context, negotiations over terms and conditions not only establish how an LP can hold a manager to account during the life of a fund, but also offer insights as to how the GP-LP relationship would function. Governance rights are a priority for many LPs, particularly what action can be taken - GP removal, key person events, no fault divorce clauses, and so on - should a manager fall short on its fiduciary responsibilities.

Fees are another consideration. While fund managers and advisors suggest the 2% management fee, 20% carried interest structure is not in imminent danger, discounts are available to those who commit a substantial sum to a fund or offer early support to a GP working towards a first close. Promises of co-investment perform a similar role.

"Some funds have a parallel non-discretionary co-investment vehicle that is there for fee reduction purposes," says Niklas Amundsson, managing director at Monument Group. "You put in $100 million and $50 million goes into the master fund at 2/20, and $50 million in the co-investment vehicle, which is no fee and no carry. On a blended basis you get 1/10."

In its annual survey of fund terms in Asia, Aberdeen Asset Management found that approximately 40% of GPs have a tiered model, with LPs qualifying for preferential rights on co-investment if they commit over a certain amount or come in at the first close. A further 40% or so have a pro rata policy with co-investment shared out equally, and the rest have no specific guidelines.

Oregon State Treasury and OTPP both make commitments of sufficient size to funds that they might be expected to receive some kind of special treatment. However, the importance they attach to co-investment differs hugely.

All of Oregon's co-investment activities are outsourced to a joint venture platform with Washington State Investment Board. In Hayes' view, this approach brings clarity to the decision-making process: there is no danger of backing "a B-minus GP that could deliver a lot of co-investment."

Musicco, meanwhile, describes co-investment as part of OTPP's DNA. The pension plan insists on participating as a co-underwriter in deals, working with the GP from day one and playing a role in the value-add process. It wants to write checks of $150-250 million per fund and seeks co-investments of at least $75 million.

This means that certain managers are too small for its remit, but the co-investment angle also imposes pressure at the upper end of the scale. There is a wariness of funds in Asia raising in excess of $3 billion and the sweet spot is seen as $1-2 billion, with the expectation of putting meaningful co-investment capital to work in a few larger deals. "If a GP needs to fill a $200-300 million equity hole - which would be rare - our hope is they put in $200 million and we put in $100 million," Musicco says.

It is possible that a GP might up with an LP base comprising: large but passive US pension funds; Canadian pension plans and sovereign wealth funds that actively lobby for co-investment; fund-of-funds that write smaller checks but are looking to fuel their own co-investment programs; and any number of smaller players that might value the chance to increase their exposure to a particular deal.

Read the small print

Distributing these opportunities - and factoring in considerations such as size and timeliness of commitment, the longevity of the GP-LP relationship, and strategic objectives like rebalancing the LP base - is a complex process. PEP and others are jettisoning the pro rata model in favor of a zero-fee approach designed for a more select group of co-investors, but they may resist making specific promises.

"During a fundraise, a significant number of investors are likely to request co-investment rights in their side letters, and larger investors often push for priority co-investment rights" says Chris Churl-Min Lee, an associate at Cleary Gottlieb. "In general, GPs try to avoid making firm commitments to provide these rights. They prefer to retain flexibility over the allocation of co-investment opportunities for each deal."

There are numerous reasons for this. For example, the GP has to take into account the individual capabilities of its LPs. If a deal is moving quickly and co-investors need to complete their due diligence within a limited timeframe, it is impractical to bring in LPs that are known for having very lengthy approval processes. PEP's Sims notes that co-underwriters are particularly useful in public-to-private transactions where the GP must show it can provide funding.

In other situations, a certain LP might be targeted because it can add value to a deal. This is where a group like OTPP would want to involve its in-house sector specialists; indeed, the way in which these teams can complement a GP's resources and strategy is included in the criteria for assessing fund commitments.

Second, concessions on co-investment may conflict with pre-existing "most favored nation" (MFN) agreements a GP has with other investors in the fund. Even if an LPA says that the GP has full discretion to distribute co-investment opportunities should they arise, larger LPs have been known to ask for side letters that give them preferential rights, in terms of first-look or percentage allocation. However, by entering into such an arrangement, the rights of other groups might be violated.

"You might see under-the-table deals between GPs and LPs along the lines of, ‘I am not going to put it in writing that I will give you preferential rights but we are business partners and we will take your needs into consideration,'" says Lorna Chen, a partner at Shearman & Sterling. "So rather than a side letter, there is an understanding between the GP and certain large LPs."

However, there are still plenty of anecdotal examples of LPs refusing to invest because they feel the terms granted to other groups are untenable, and GPs with unwieldy LPAs that require co-investments to be shown to every single fund investor. As with other terms and conditions, the level of flexibility comes back to how badly a private equity firm needs the money.

"If you are struggling to raise $400 million and someone offers $80 million but they want first-in-line co-invest, what do you say? That you have to keep it open?" asks Andrew Ostrognai, a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton. "So you give them first-in-line rights and that virtually assures you won't get the second $80 million check from an investor that likely wants to co-invest, because that investor won't take second-in-line. But what is worse - not getting the second $80 million or getting nothing? At a certain point you take the leap."

Just as there is an element of cyclicality to private equity fundraising that influences how much GPs must concede on terms and conditions, some LPs are likely to reconsider their position on co-investment.

A number of groups led the way, building teams able to evaluate and execute transactions, and others have followed, regardless of the fact they aren't properly set up to do co-investments. Those that rush into every single opportunity presented to them without conducting proper due diligence are likely to run into trouble. They may ultimately conclude that the risks outweigh the returns.

"It takes some time - you can't just look at 1-2 years of results - but in the medium term your co-investment returns have to be better than your fund returns," says LGT's Coulter. "If a new CIO comes in, asks why the co-investment results are worse than the fund results, and the answer is because you've just been doing top-down box-checking work, he is likely to say, ‘We are either going to build up a proper co-investment team or we will stop doing it."

But even if only a small portion of those under-resourced LPs start taking co-investment seriously, there will likely still be increasing amounts of capital available from the big players. One reason for this is the expectation of more deal flow out of Asia.

Canada Pension Plan Investment Board's (CPPIB) $534 million contribution to the MBK Partners-led $6.4 billion acquisition of South Korean retailer Homeplus is extraordinarily large by regional standards. Indeed, CPPIB previously reduced its minimum check size for co-investments in Asia from $50 million to $35 million in order to capture more deal flow. But as economies mature, and more control deals become available in emerging markets, large-cap transactions should proliferate, albeit gradually.

The big get bigger

The more capital these investors want to deploy, the greater their demand for customized solutions from GP partners. Fund formation lawyers are already seeing a rise in separate accounts that exist alongside but independent of traditional co-mingled funds. For these vehicles, terms and conditions are subject to a completely open-ended negotiation. "There is no one-size-fits-all answer," says Debevoise's Ostrognai. "It is not a question of what other LPs are getting; there are no other LPs."

Nevertheless, a separate account could have an impact on co-investment opportunities available to LPs in funds run by the same manager. It makes the web of agreements around preferential rights and fiduciary responsibility all the more complex.

This change may only be happening at the margins but it points to a fraying in the traditional GP-LP relationship and the terms that bind it. If the industry is to become increasingly customized, for sophisticated investors making large commitments or for groups that want special treatment in return for taking a risk on an emerging manager, the onus falls on the GP to manage the process. It is then a question of internal resources and what the leaderships and back office can accommodate.

"You want to keep it simply MFN, you want to keep straight," says Mark Chiba, group chairman and partner of The Longreach Group, a Japan and North Asia-focused PE firm. "You don't want 20 LPs with 15 different economic relationships because people choose different packages. At the end of the day, you are trying to take their capital and multiply it - that should be the basic objective. If you make terms too complex or heterogeneous they just become a distraction.

SIDEBAR: Fees - Marginal movement

Guy Hands, founder and chairman of Terra Firma, announced earlier this year that his next fund would not charge fees on uncommitted capital. "This means there will be no pressure from investors. We can take our time and deploy capital in an opportunistic way," he told AVCJ.

There are said to be GPs in Asia considering a similar approach, but the trend has yet to take hold. Indeed, while some LPs push for fee breaks in return for making early or substantial fund commitments, industry participants say the 2% management fee, 20% carried interest model is more or less intact.

"The downward pressure has largely been driven by LPs' view that managers shouldn't make profits on management fees," says Chris Churl-Min Lee, an associate at Cleary Gottlieb. "If a smaller manager goes out to raise a larger successor fund with essentially the same team, LPs might push for lower fee rates or one or more step-downs in the fee rate above certain fund size thresholds."

The 2/20 model is described many as "a good starting point" for negotiations. Anything over $1 billion and it becomes difficult to defend 2%; below $1 billion and there is less push back. Several LPs express discomfort at the notion of extracting discounts from smaller managers that might be struggling to get traction on a fundraise, although the practice is not unknown.

"We've done around 50 first-time institutional funds and there are situations where terms are untenable," says Chris Lerner, a partner with placement agent Eaton Partners. "If you are trying to build a business and you have an operating budget for that and you are being squeezed to take a discount it becomes difficult to run the business. The GP and advisor must have a good idea of what the operating budget is and then what fund size and fee string they need."

For some investors, the ideal scenario is using an operating budget, not 2%, as the starting point. "The GP presents a budget to the advisory board and then they back into a management fee based upon that," says Doug Coulter, a partner at LGT Capital Partners. "It's a transparent process, and in the cases I've seen, it tends to be less than 2%."

There is also variety in the hybrid structures that are emerging in Asia. If a GP a wants to build up its track record and with a view to raising a traditional blind pool fund in the future, it might line up several deals and invite LPs to participate in a shorter-term structure. There are examples of fee breaks beyond the standard 25 basis points and even GPs charging no fees at all.

However, with zero-fee co-investment increasingly used to ease the financial burden on LPs, the focus is more on other charges. With the US Securities & Exchange Commission honing in on PE firms' approach to monitoring fees and board fees levied on portfolio companies, the real pressure is on management fee offsets.

"Some of that historically has gone straight into the GPs' pockets, but over the years it has shifted in favor of LPs," says Wen Tan, a partner at Aberdeen Asset Management. "The proportion of funds in Asia with a 100% management fee offset has increased from 48% in 2009 to 84% this year."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.