China take-privates: New wave

Recent volatility notwithstanding, plenty of investors want to back China take-privates with a view to domestic re-listings at higher valuations. The company founders behind these deals are the big winners

A few weeks ago, Shanda Games appeared to be on the cusp of a potentially lucrative re-listing. The Chinese company departed NASDAQ in November following a $1.9 billion privatization, by which point the chairman and his partners had a shell in place for a reverse merger on the domestic bourse. Now, though, the process is in limbo with several parties facing legal action from disgruntled investors.

When the take-private was announced in early 2014, Primavera Capital was controlling shareholder Shanda Interactive's partner in the deal. Over the next few months, FountainVest Partners and The Carlyle Group came on board.

But by September they had been replaced by a slate of local investors and Shanda Interactive sold control of the business to a unit of textiles producer Zhongyin Cashmere, and Yingfeng Zhang, chairman of Shanda Games. A source familiar with the deal told AVCJ that the change was driven by insiders concluding "they could do it themselves," be free of the strictures of working with private equity, and enjoy more of the upside.

Eight entities appeared on the company's proxy filing, three connected to auto parts manufacturer Zhejiang Century Huatong Group and the rest to Zhongyin or Zhang. Court filings indicate that Zhongyin syndicated out of its holding through a string of separate vehicles, raising RMB2.15 billion ($326 million).

The first complaints came from investors in those vehicles, who filed domestic lawsuits claiming that the take-private had been oversold by Zhongyin and they had been allocated shares worth less than a quarter of their principal. Then Century Huatong, which has a 42.7% stake in the business but a minority voting right, took legal action in Hong Kong and the Cayman Islands. It said the majority shareholders resolved to recut the deal and cash out Century Huatong at a lower price than it paid for its shares.

Shanda Games is an extreme example of a take-private gone wrong, but it offers a snapshot of the feeding frenzy around US-listed Chinese companies. Local money is pouring into these deals - sometimes at the expense of PE - in order to leverage the arbitrage opportunity of listing companies in China at higher valuations than they are bought in the US. Satisfying every interested party can be challenging.

"It is not just a private equity play. Other institutional investors - like insurance companies, commercial banks and asset management companies - keen to participate, and banks will lend significant amounts to support these transactions," says John Gu, a partner at KPMG. "Taking part in these deals can mean a handsome gain post-listing, so if you have a domestic investor pricing aggressively, PE investors could get squeezed out in some instances."

Motivating factors

For all privatizations involving US-listed Chinese companies, there tend to be two primary drivers: the compliance costs that come with being a publicly-traded company in the US and whether they justify the exposure to a broader and more sophisticated pool of investors; and the size of the gap between the valuation at which a company trades in the US and what it might achieve domestically.

Take mobile game publisher iDreamSky Technology, for example. The company's revenue ballooned to RMB984.1 million in 2014 as it sought to build scale - swinging from a net profit to a net loss as a result of rising customer acquisition costs - in preparation for a NASDAQ IPO. IDreamSky went public in August 2014, raising $116 million in its IPO and paying out $4.65 million in accounting and legal fees and another $2.54 million in annual auditing costs.

The stock peaked a month later but then sank below the $15.00 offering price. It closed at $10.53 on June 9 of last year before a small surge ahead of a take-private offer of $14.00 per share, which values the company at about $600 million.

Meanwhile, one of iDreamSky's competitors, Beijing Kunlun Technology, listed in Shenzhen in January 2015 and has since seen its share price increase by more than 400%. With revenues of RMB1.9 billion in 2014, it has a market capitalization of RMB42 billion and trades at a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 115. Another, China Mobile Games & Entertainment Group, was taken private last August at a valuation of $690 million and is set to be acquired by Century Huatong for RMB6.5 billion.

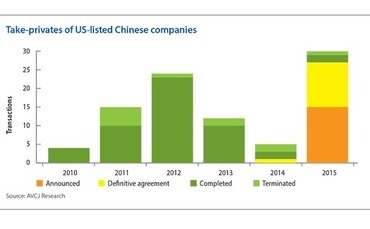

The balance between these two driving factors has contributed to two distinct waves of take-privates. The first came in the wake of a handful of accounting scandals involving Chinese companies that led to eroded valuations across the board. AVCJ has records of four announced transactions in 2010 - some of which featured PE - rising to 15 in 2011 and then 24 in 2012. Six failed to transact and the rest have closed.

Deal flow then slowed for a couple of years before rebounding in 2015, with 30 take-privates announced. Of these 20 fell in the first six months of the year as founders and their partner investors targeted re-listings in the then-soaring local markets. Close to half of these companies have entered into definitive agreements or completed privatizations. A notable difference between the two waves is the size and profile of companies involved.

"In 2011-2012, most of the companies had market caps of $100-500 million and a lot of them got listed through reverse mergers," says Donald Yang, managing partner at Abax Global, which provided structured financing for a few early deals. "Now you see some really large companies that perhaps should be listed in the US but want to return to Asia to get better valuations. Because the profile of the companies has changed, large PE firms are more involved, and it has become mainstream investing."

With this in mind, transactions can be divided into pre- and post-Focus Media. At $3.7 billion, the take-private of the outdoor advertising firm - announced in August 2012 - was at the time the largest of its kind. Thirty months after the deal closed, Focus Media re-listed in Shenzhen through a reverse merger. The shell, Hedy Holding, has dropped 20% since the start of the year, but still has a market cap of RMB138 billion.

This translates into a large paper gain for the likes of The Carlyle Group, FountainVest Partners, CITIC Capital Partners, Primavera and China Everbright. It also laid down a marker - in terms of multiple and timescale - for others to aim for. As a result, demand for exposure to China take-privates, from insurance companies to high net worth individuals, has taken off.

"The Focus Media deal gave people a lot of clarity in terms of the A-share exit and it attracted a lot of investors, particularly domestic investors, to going-private transactions," says Ning Zhang, a partner at Orrick. "Even though the deal wasn't as fast as some expected and the investors are still subject to a three-year lock-up, it gave people a lot of comfort that they can get into the A-share market pretty quickly."

Multiple actors

Of the take-privates announced between 2010 and 2012, only two had more than three PE sponsors who were not existing investors. However, the need for equity has increased in line with rising deal size. The consortium in place when a bid is announced is not necessarily the same as the one that does the deal, in part due to the number of willing participants.

WuXi PharmaTech is a case in point. When Ge Li, the company's founder and CEO, announced his $3.3 billion bid last May, healthcare-focused PE firm Ally Bridge Group - which initiated the deal with Li - was the only other name on the filing. Boyu Capital is understood to have been involved from an early stage as well. By the time the deal won shareholder approval in mid-December, Temasek Holdings, Ping An Insurance, three more PE firms, and an investment entity connected to Shanghai Pudong Development Bank were also in the consortium.

"Immediately after the deal was announced we had a very strong indication that it would be well oversubscribed - and that's exactly what I had expected when suggesting the deal," says Frank Yu, founder of Ally Bridge. He cites the rapid growth and quality of WuXi's R&D and contract manufacturing outsourcing business, and the global nature of its pharmaceutical sector client base, as reasons for the strong interest in the deal.

Asked about the challenges WuXi faced in meeting investor demand, Yu observes that "for any well-oversubscribed deal, you have headaches," and stresses the importance of putting together a consortium that is aligned with management on issues such as business development and exit strategy.

This tallies with other accounts of a controlled but somewhat frenzied process, with various interested parties lobbying the founder for a slice of the action. For Qihoo 360 Technology, the situation was similar, but based on the final investor roster, magnified several-fold. Sequoia Capital and Golden Brick Silk Road Investment were there at the beginning, but the latest proxy filing for the $9.3 billion deal lists them among 36 parties with equity commitment letters.

A key difference between the two processes is that WuXi was from the outset a partnership between founder and PE: Ally Bridge's Yu had a longstanding relationship with Li, while Boyu co-founder Sean Tong, during an earlier stint at General Atlantic, was on the WuXi board ahead of the company's 2007 IPO. There is said to have been no lead financial sponsor for the Qihoo deal.

"Anchor investors participate actively in the process and negotiate with the founder who is sponsoring the take-private. But some of the more recent deals have been founder-driven and they are getting money from banks and other investors," one industry participant notes. "As deals are getting larger, financial investors' influence is decreasing. If you put $300 million into a $9 billion deal, it doesn't mean that much."

Numerous considerations come into play when a founder is primarily responsible for allocating places in the syndicate. They want certainty that a deal gets done and perhaps a chance of a quick re-listing, which may push them towards domestic institutions that have financial or regulatory clout. For example, while Ping An Insurance is investing in WuXi, Ping An bank is providing debt for the take-private.

These deals can also be personally and politically sensitive. Whatever the desire to create a balanced consortium of blue chip investors, founders will come under pressure to cut family and business acquaintances into a transaction. There may also be local government investment funds that need to be satisfied.

"There is a finite number of these deals so potential investors compete aggressively for consortium shares, but there might be a state-owned arbiter ultimately in the middle of it," says Charles Comey, a partner at Morrison & Foerster. "Alternatively, if you are a private deal promoter, you can preempt a lot of the conflict and help ensure availability of acquisition debt financing by giving government-affiliated funds access and telling the other guys, ‘We are doing this as a necessity and we are letting you guys in as a favor, here's your percentage.'"

Foreign PE firms are still participating in take-private deals but local capital is playing a much more significant role than before. There may be good reason for this. In situations where direct foreign exposure to certain assets is prohibited, variable interest entities (VIEs) were inserted into corporate structures ahead of offshore IPOs. VIEs are not allowed in domestic listings, so if a business is restructured onshore, the foreign investors may have to exit. Last year, regulators said that in most situations minority participation would be permissible, but some companies don't want to take the risk.

However, the overriding issues for founders are likely to be pricing and flexibility. Aggressive local investors that want to get into take-private deals - and don't have the same kind of fiduciary or governance requirements as international PE firms - might offer management more equity in the post-acquisition entity and greater leeway in the development of the business. If this proposition is paired with attractive local financing for the deal, all the better.

"The amount of money available from equity and debt investors in China, and also from offshore funds, naturally gives the founder quite a bit of leverage," Orrick's Zhang observes.

The growing popularity of onshore structures that are a logical stepping stone to domestic listings open up these deals to a wide range of investors. While the co-CEOs of Mindray Medical have agreed a $3.3 billion take-private with $2 billion in debt and little or no external equity support, Qihoo's 36 equity backers include six insurance companies, four private equity firms, handfuls of corporates and asset managers, and a host of entities that could be corporate M&A funds or high net worth vehicles.

For example, one participant is an M&A fund set up by Huatai Securities that has received commitments from several Chinese corporates. Another is a project fund launched by Huarong Securities with the sole purpose of raising capital to support the Qihoo deal.

Execution risk

The Shanda Games situation flags up the risks that come with investment agreements in China, but the nagging uncertainty with these deals is what happens if the second part of the strategy - the re-listing - fails to work out as planned. Many investors are motivated solely by the prospect of multiples arbitrage and it is unclear what certain players have been promised, or led to believe, in terms of the speed and size of exit.

"Some people might end up disappointed," says Abax's Yang. "If you look at the A-share market, there are a lot of moving parts. Regulations are changing, there is a lot of retail participation and many investors are not sophisticated. That is why you see all this volatility. You never know what will happen to valuations when the lock-up expires."

There has been a slowdown in take-private activity since the severe market correction in the middle of 2015 and the pricing on a number of deals has been revised downwards. However, KPMG's Gu notes that transactions are still in process, with investors withstanding short-term valuation pressure in the expectation of a higher valuation through an eventual domestic re-listing.

Rather, the concern is that the length of the queue to list domestically, and the tighter qualification requirements than for the US markets, will result in a longer wait for some companies and perhaps an aborted processes for others. And if a company has gone private with a financing package predicated on a reasonably swift re-listing that has yet to happen, it will need operating cash flow to satisfy creditors.

This is why investors flock to larger businesses that are seen as likely candidates for reverse mergers. There is also talk of further expediting the process by involving the listed shell to be used for the reverse merger in the initial acquisition, much like an M&A deal. Tsinghua Unigroup, an investment unit under Tsinghua University, is doing this with Xueda Education. The transaction is being led by a Shenzhen-listed subsidiary with the parent providing financial guarantees. It leaves the option of a share issue to generate additional financing.

The broader question is how much longer the take-privates can last. The previous wave eased off as the valuation gap between the US and China narrowed. Even if this doesn't happen for the current batch, there are only so many companies suited to a domestic re-listing - because they already have a strong following in the US or because their business is not as relevant to domestic investors.

The other factor is regulation. China wants local investors to share in the success of local companies and it is willing to offer incentives. An international boards that allows offshore-traded firms to sell shares domestically is one option, but there are also plans to liberalize domestic listing requirements and open up cross-border activity. This would enable companies to pick the bourse that best meets their needs.

"It is a more for the long term than the short term, but that will naturally end the take-privates because people will try to figure out at the beginning which market is the best one for them," says Orrick's Zhang. "In the past, some companies went to Hong Kong or the US because they didn't have the choice or because they saw better multiples."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.