Frontier market fundraising: Roads less travelled

As fundraising slows globally, GPs in frontier markets are more dependent than ever on multilateral development banks. That’s not a major problem now, but in a long downturn, it could become one

Dolma Fund Management quietly defied the toughest global private equity fundraising environment in recent memory last December, closing its second vintage well above target with a single-country mandate – and in a frontier market at that.

The Nepal-based investor raised USD 72m, exceeding a target of USD 60m, thanks to support from a mix of development finance institutions (DFI), including British International Investment (BII). The LP base was different, though still DFI-dominated, when Dolma closed its debut fund on USD 36.6m in 2018.

While the fund was launched in the midst of pandemic gloom, most of the capital was raised prior to the outbreak of war in Ukraine and the subsequent erosion in global LP appetite. Still, Dolma was utterly dependent on DFIs, which are mandated to take frontier market risk. Conversations were initiated with several global non-DFI investors but there were no follow-ups, even with dedicated impact units.

The key proof-of-concept during the fundraise spoke to the capacity of the digital era to de-risk frontier markets. Dolma sold a significant position in Kathmandu-based artificial intelligence (AI) specialist Cloudfactory as part of a USD 65m Series C in late 2019. Another portfolio company, Fusemachines, is active in generative AI and considered ripe for a similar liquidity event.

"Nepal will never be a manufacturing powerhouse because it doesn't have the necessary infrastructure, but it does have good broadband, and therefore you can run businesses out of Nepal that serve the global market," said Tim Gocher, founder and CEO of Dolma. "That's an incredible thing. The new digital economy for frontier markets is a huge space for us."

Gocher added that traction in technology – as well as some of Nepal's points of resilience in light of global stresses – contributed to genuine interest among the international LPs that did not commit. For now, though, they concluded that more reliable returns can be obtained in more familiar markets.

The dearth of non-DFI support in frontier markets is nothing new, but the situation appears to be going from bad to worse in the current macro environment. Importantly, this vacuum includes endowments and foundations that helped establish much of the PE landscape in frontier Asia in the first place.

The DFIs and related government entities remain a reliable source of capital for GPs in these jurisdictions. However, if the current mood of heightened conservatism among institutional investors persists too long, that reliability could also come into question.

Craig Gifford, an investment director responsible for South Asia private equity funds at BII, notes that uncertainty around non-DFI support for a frontier market manager in future vintages makes it hard to commit. Indeed, BII's investment in Dolma's second fund, made over two years ago, was its most recent in a frontier market.

A shallow pool

A more immediate concern is that there are simply not enough sufficiently institutional funds on which to take a chance.

In South Asia, Nepal has counterintuitively pulled ahead of Bangladesh as the leader in terms of ecosystem development. This includes recent improvements in the regulation of PE funds and a warming trend in terms of founder willingness to accept outside investment.

About 15 new fund managers are said to have launched in Nepal in the past two years, although they are generally sub-USD 10m and have yet to attract foreign LPs. Outside of Dolma, only Business Oxygen (BO2), a climate-focused GP, has raised DFI capital in the country. No fund has achieved a final close in Bangladesh or Sri Lanka since 2019 and 2017, respectively, according to AVCJ Research.

"To get to a size that is large enough for a fund to operate in frontier markets, we need at least three to four DFIs to join in the first close," Gifford said. "So, it's not just about dealing with the GPs – we have to collaborate with other DFIs. If there's a non-DFI in there, that's all the better, but we're seeing limited traction there."

VC is considered an area of short-term hope despite the global retreat from technology risk. Pakistan is the standout story in South Asia of late, with Lakson Venture Capital raising USD 10m in 2019, Indus Valley Capital raising USD 17.5m in 2021, and Zayn Venture Capital raising USD 25m in 2022.

These funds received scant international investment, and none are backed by DFIs. The exception is Techxila Fund, a joint venture of local conglomerate Fatima Group and China's Gobi Partners, which collected USD 20m in 2021 with support from BII.

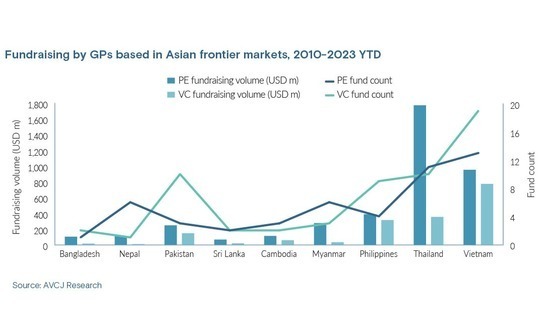

This feedback is reflective of longstanding woes. Only about USD 5.8bn has been raised across 97 PE and VC funds based in Asian frontier markets since 2010, according to AVCJ Research. Thailand and Vietnam alone accounted for USD 3.8bn of that with 53 funds.

The perennial challenge is how to get more global, non-DFI capital into frontier markets when IRR expectations are commonly as low as 5% and there remains a lack of demonstration effect in terms of exits and distributions. Furthermore, there is little incentive in DFI mandates to demonstrate liquidity by pursuing exits through secondary channels.

All this has been exacerbated in the recent term by warbling post-pandemic GDP growth rates, the relative strength of the US dollar versus local currencies, interest rate pressure on low-margin businesses, and a general tendency for global LPs to hunker down in their home markets amidst geopolitical and macro uncertainty.

Untapped potential

To some extent, the pain is mitigated by the fact that funds are small and therefore more likely to hit target, as well as the idea that the markets themselves remain underpenetrated. From a global allocator's perspective, frontier markets are shallow with only a smattering of accessible companies large enough to withstand economic shocks. On the ground, the field is described in more welcoming terms.

"Like everywhere else in the PE fundraising landscape, there has been a slowdown of international investor proactively seeking out opportunities in the region," said Panaikorn Chartikavanij, a managing partner at Thailand-based and Greater Mekong-focused Lakeshore Capital.

"On the other hand, our target geographies continue to be significantly underpenetrated by PE and we haven't seen any serious competitors arrive in the past couple of years, at least when compared to other Asia Pacific regions. We've therefore been focused on finding the best investment opportunities and harvesting our fund assets to achieve the return targets of our LPs."

Lakeshore closed its second fund on USD 150m in 2021 with about a quarter of the capital coming from DFIs and much of the rest coming from Japanese and European institutional investors. This is a highly diversified LP base compared to that of the firm's more DFI-reliant debut (USD 60m in 2015), but it's an open question whether that weaning-off could continue with Fund III under current macro conditions.

Chartikavanij said he expected future fundraising to include a small number of DFIs while "retaining the ratio" of international commercial investors. Ricardo Felix, head of Asia Pacific at Asante Capital, a placement agent that supported the Lakeshore fundraising, is less optimistic, predicting that more DFIs will have to be brought on board to scale future vintages, including those that were not able to participate in Fund II for timing reasons.

The idea that normally China-bound LP capital could be diverted to frontier markets remains theoretical but also a realistic case for optimism. Niklas Amundsson, a partner at placement agent Monument Group, has observed a trend in the past year of global institutional investors setting up bases in Singapore to explore the region, including its frontier fringes.

"For some of these organisations, you have people who are in charge of looking at China and they need to reinvent themselves," Amundsson said. "I don't think any of these fund-of-funds or asset managers are looking to deploy capital into these markets in 2023, but they're certainly starting to populate their databases and looking at these markets in a very different way than a few years ago."

When Monument worked on the second fund of Philippines-based Navegar in 2019 – a USD 197m vehicle backed largely by DFIs and local corporates – the response from global financial investors was weak. Only half of the organisations expected to be interested took a meeting, and there were no second meetings.

"They're all in Manila in 2023. I think there were 15-16 visits to Manila last year," Amundsson added. "I believe in 2024 or 2025 they're going to start making investments. They're not going to deploy a lot of money, but they're going to do things they've never done before because they're going through the landscaping exercises. That's exciting."

Friendly families?

In the meantime, beyond DFIs, family offices remain the lowest-hanging fruit for frontier managers, especially those that are relatively personality-driven and keen to explore offbeat opportunities. The sticking point is that, in a risk-off market, it is even less likely than usual that those family offices will receive endorsements of frontier market opportunities from generalist consultants.

Singapore-based Collyer Capital, a pan-Southeast Asia fund-of-funds investor hopes to help fill this hole. The firm, co-founded in 2021 by Eric Marchand, formerly of Unigestion, Campbell Lutyens, and BII, is seeking USD 100m for its debut vehicle. An anchor commitment has been secured from a European asset manager, but the bulk of the capital is expected to come from family offices.

Collyer will invest in non-frontier ASEAN markets as well, but there is a strong focus on geographic diversification across the region. This is expected to hedge foreign exchange risk by establishing a balanced basket of currency exposures.

Much of Collyer philosophy is rooted in the current bearishness challenging frontier managers. The VC craze is dead. Tech risk should be addressed soberly. Profitable companies in proven industries are preferred because exit options remain a wildcard. Safety is in the quality of the managers and their underlying companies, not their quantity or size.

"We're not seeing waves of capital coming into Southeast Asia, but we're seeing additional interest from people who recognise the fact that diversification in the region will lead to stability, low volatility, and returns," Marchand said. "We're not saying we're going to beat the market – it's a steady ship and we're thinking a lot about liquidity."

The idea of bringing conservatism to frontier market risk is also getting traction on the venture capital end of the spectrum, and this is proving feasible even without DFI backing.

Hong Kong's Betatron Venture Group offers a case in point. The firm is targeting USD 50m for its first proper fund; three prior sub-USD 10m funds were structured as special purpose vehicles. It invests across Asia, not specifically in frontier markets, but Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Cambodia are on the menu.

Betatron reached a USD 15m first close last year and claims to have added to this significantly. The investor base is entirely family offices and high net worth individuals, reflecting the firm's accelerator roots. Frontier risk is mitigated by ensuring that investees in those jurisdictions have some presence or exposure in other, stabler markets.

Arshad Chowdhury, a general partner at Betatron, observes that much of the LP interest in the fund stems from a focus on real-world problems in large industries rather than trends around technology and innovation. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs), Web3, and models such as buy-now, pay-later (BNPL) were never part of the plan.

"Betatron's view on resilience is something that used to work against us but now works in our favour. There was a time when LPs were disappointed when we said we didn't invest in mainland China or crypto because there was so much excitement around those asset classes," said Chowdhury.

"We've become allergic to pure frontier plays nowadays. We shy away from frontier market start-ups that are exclusively frontier more so now than in the past."

Political landmines

Reliance on a less institutional LP base is also seen as a strategy for averting a rise in political complications around funds targeting frontier markets.

The standout example in this regard is Myanmar, where a military coup in 2021 has rendered the country un-investible. Several GPs have institutional backing in the country – mostly DFIs – but most of these LPs are said to be quietly winding down their exposure and effectively writing the country off as a loss.

Meanwhile, LP appetite for political risk has fallen dramatically. This is evidenced to some extent by a perceived trend in frontier markets whereby fund documentation increasingly includes clauses about avoiding deals with politically exposed persons (PEPs).

"It's going to make it difficult for DFIs to invest in post-conflict frontier markets, including Sri Lanka, where there are restrictions on PEPs," said a fund manager in Myanmar. "The individuals involved will have their hands tied behind their backs because they have to stand up in the legislature and explain why this European government is doing this. So, it's easier for them to do nothing."

For its part, BII has specified that its experience in Myanmar has not influenced its stance on backing funds in other politically fragile or post-conflict markets, although the episode has provided "valuable lessons" to inform future investments.

Nevertheless, the meltdown in Myanmar and themes such as PEP restrictions have fed concerns about the ability to raise funds in politically fragile markets across Asia. Much of this boils down to the idea that first-time managers without much experience navigating socioeconomic shocks will be less palatable to government-linked investors, including DFIs.

To some extent, these concerns have been reinforced by observations that DFIs are increasingly open to backing frontier market managers' third and fourth vintages – presumably at the expense of small and scrappy first-timers.

DEG, a German DFI and a backer of Navegar, typically comes in as an anchor and first close investor, but in most emerging markets in Asia, it requires visibility on strong follow-on participation by private, commercial investors. "In the current difficult fundraising environment, this is indeed easier said than done," said Markus Bracht, a vice president responsible for Asian funds at the firm.

The question for frontier Asia during a time of commercial LP hesitancy is therefore whether it is a systemic problem for funds to remain overwhelmingly comprised of DFI money. Small funds with small underlying businesses currently serve those investors' impact agendas well, but a lack of scale and LP diversity in the long term may not be acceptable.

"At least for a limited period, we need to accept a moderately higher DFI concentration. Nevertheless, DFIs cannot fully compensate for significantly less private investor money," Bracht said. "In many cases, we see fund volumes being lower than initially planned. Reduced fund sizes can be an interim solution but only as long as the investment strategy can still be executed and teams are still incentivised."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.