Asia private credit: Muffled momentum

The conservative virtues of private credit relative to private equity have come into fashion in a risk-off world. But global participation in the Asian side of the story will be limited

Private credit investors across Asia claim to be seeing their best returns since the fallout from the global financial crisis, often on par with private equity but with a fraction of the risk. This is in the context of public market dislocation and a general trend toward downside protection amid rising macro uncertainty. Unsurprisingly, they have largely decided it's a good time to speak to LPs.

Almost every global and regional investor contacted by AVCJ for this story is in the process of raising an Asia credit fund. The few who are not have closed one in the past year. It's an anecdotal cross-section in a niche geography for the asset class, but it helps put a regional face on the global picture.

After more than a decade of steady growth, global private debt fundraising hit an all-time high of USD 224bn in 2022, according to Preqin. While AVCJ Research confirms less than 10% of this was in Asia, there were significant milestones in the activity.

PAG closed its fifth pan-regional private credit fund last December on USD 2.6bn, marking the largest direct lending fund raised in the region to date. Two months earlier, Baring Private Equity Asia's recently spun-out credit unit closed its third vintage on USD 475m.

This coincided with Bain Capital raising USD 2bn for an Asia special situations fund and KKR raising USD 1.1bn for its debut Asia credit vehicle. Other multi-strategy managers primarily target the region through global funds, but they are also bullish on the opportunity set.

"We're huge believers in private credit – we view this time as a golden moment for the sector. Particularly in an environment of rising rates and high volatility, private credit can help investors protect against downside risk and diversify income streams," said Mark Glengarry, head of Asia Pacific credit at The Blackstone Group.

"In addition, companies are increasingly looking for flexible capital solutions as public markets pull back. This provides tremendous opportunities for private lenders like Blackstone, which can step in and deploy capital at scale."

Addressable markets

Blackstone's global credit business is worth USD 255bn, but it didn't enter Asia until last year. Still, in 2022 alone, the firm committed more than USD 800m across five transactions in the region. The largest of these was an anchor commitment to support BPEA EQT's USD 2.7bn acquisition of Hong Kong corporate services provider Tricor.

Blackstone expects to have USD 5bn in assets in the region in the near term. Last March, it launched a Japan private credit fund in partnership with Daiwa Securities Group.

Like many of its peers, Blackstone observes that private credit has delivered better historical risk-adjusted returns over the last 15 years versus fixed income. It claims to have designed its platform to meet the challenges posed by inflation and rising interest rates.

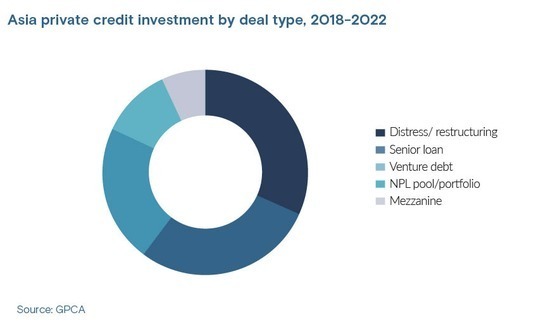

Senior-secured lending to performing companies in growing sectors is the dominant strategy. Indeed, senior loans accounted for 29% of all private credit investment globally between 2018 and 2022, second only to distress on 32%, according to the Global Private Capital Association. Venture debt came in third with 22%.

"Right now, my sense is that the markets in Asia that have common law recourse are going to offer enough opportunities that you don't need to concentrate on Southeast Asia, India, and China for higher returns," said Chris Mikosh, co-founder of Hong Kong-based Tor Investment Management.

"If we're going to do a deal that involves entities in one of those jurisdictions, it's going to be on a cross-border basis, where we have collateral and recourse in the more developed markets."

Tor was founded in 2013, raised USD 250m for its first pan-Asian credit fund in 2018, USD 350m for its second in 2020, and is targeting up to USD 700m for its third. China has historically represented less than 10% of funds. Assets under management currently stand at about USD 2.5bn, mostly in private lending.

The firm, which competes in the large-cap space with the likes of Bain and KKR, is tracking gross returns of around 20%, compared to a low to mid-teens range two years ago. It has raised USD 250m for Fund III to date, mostly from North America.

Mikosh notes that in the past six months, interest in the asset class has increased among North Asian pensions and institutions, as well as Southeast Asian sovereign wealth funds. But he cites now all-too-familiar fundraising challenges, notably geopolitical stresses and LP indigestion around the denominator effect. There is also the idea that many global LPs see comparable returns to be had in their home markets.

Deep benches?

All these headwinds are magnified in middle market and developing economy-focused strategies. Navis Capital Partners launched its credit unit last year with the recruitment of Justin Ferrier, previously of BlackRock and ADM Capital.

Timing for Navis was more about firm-level readiness than tapping into the rising prominence of the credit opportunity in the current slowdown. The idea of a credit strategy had been on the back burner for years, but the firm needed to get its exits back on track post-pandemic and find the right person to lead the business.

With some USD 1.8bn returned to LPs in the past 18 months, the timing seemed right. Navis is reportedly seeking USD 350m for its debut credit fund; Ferrier declined to comment. The plan is to provide secured lending across Southeast Asia to the kinds of small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that missed out on traditional bank financing due to an arguably over-rigorous scoring system.

"Banks in Asia continue to pull back, given what's happening in the US, so they're demanding better credit ratios and better pricing, and they're becoming more selective in terms of credit quality," Ferrier said. "That means less lending to the lower middle market corporates, which in turn results in better-quality companies coming to us on better terms."

Navis' key gambit in entering the credit game is its private equity skillset and related connections, especially around operational support and guidance on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) inputs. The logic is that this provides investees with the less dilutive, down-round-avoiding financing they seek, plus the more hands-on consulting associated with PE.

The concept hasn't been lost on pure-play credit investors contending with an influx in competition. Hong Kong's ADM claims differentiation in targeting a "missing middle" just north of venture debt with transaction sizes around USD 20m-USD 70m. More importantly, the firm notes that its presence across the region allows it to advise investee companies on cross-border transactions.

At any given time, ADM has about USD 2bn in assets under review, and that pipeline has not enlarged in the current market. But pressure on SMEs has allowed the investor to leverage improved lending terms and diversify its options for collateral.

ADM is currently in the market for its fifth secured direct lending vehicle, which is part of a broader USD 1bn fundraise. This has coincided with China, the largest exposure in recent years, being reduced in proportion.

"In Asia, fund managers must help allocators understand the underwriting nuances that underpin successful regional direct lending strategies. But we're seeing renewed enthusiasm, particularly as other emerging markets are becoming more challenging due to rising interest rates," said Sabita Prakash, a managing director at ADM.

"Occasionally, investors in other regions may have a preconception that Asia is only China. We're not downplaying China – we're talking about the excitement that is India, Southeast Asia and Australia. It's about rebalancing the conversation to be about Asia Pacific – and the diversified, increasingly intra-regional, uncorrelated financing opportunities – rather than just China."

It must be said, however, that a longstanding, intra-regional presence – even when coupled with large-scale resources and global heft – is no panacea for the many pitfalls of Asian credit.

KKR provided one of many cautionary tales in this sense with KKR India Financial Services, (KIFS) a non-bank lending business set up in 2009 that received some USD 150m of investment up to 2020 and deployed around USD 5bn.

Underperformance made KIFS a poster child for the challenges of private lending in India's SME space, with most of its loans said to be at risk of default as of late 2019. Last year, KKR merged the business with InCred, a similar non-bank lender that is expected to wind down the KIFS book.

Even more prominently, Avenue Capital Group raised USD 3.1bn for its fourth Asia fund in 2006 – up from USD 628m for the previous vintage – expecting to invest USD 1bn in China nonperforming loans (NPLs). The private equity firm struggled to deploy the capital, however, and fund performance suffered.

Over the coming years, numerous investors examined the portfolio with a view to doing a secondary deal. This eventually led to a reboot of the strategy in partnership with the special situations team at PAG and the launch of a successor special situations fund, more modestly sized at USD 450m in 2018.

Other global firms have also experimented with different strategies as they sought entry points that delivered substance and scale. The overriding takeaway is that local knowledge and resources are essential to any foray into Asian private debt.

"Even with a strong global private credit franchise and almost two decades of experience in the space, we have found it critical to develop an on the ground presence in the major markets in Asia and be seen as a local player and consistent market participant, with strong relationships in the end markets," Brian Dillard, KKR's head of Asia credit, said about entering the region generally and not referring to either Avenue Capital or KIFS.

"We think Asia will remain a very difficult market to cover on a fly-in, fly-out basis and also observe that many of our best deals are proprietary-bilateral or are shown to a very small group of trusted counterparties at the local level."

Global vs local

Dillard added that KKR has structured its credit business in the region to leverage its local Asian country teams across different alternatives products, combining those specialisations with risk-management components from the global private credit franchise.

He also noted that the best opportunities are in performing private credit, although most Asia-dedicated private debt capital has taken aim at higher-risk, higher-return strategies. In addition to launching its debut Asia credit fund last year, KKR has committed to invest at least USD 1bn alongside Abu Dhabi's Mubadala Investments in Asia performing credit opportunities.

Andrew Tan, head of Asia Pacific private debt at Muzinich, is tracking the encroachment of new global players into Asia but doesn't expect competition to increase in the small-cap space his firm prefers. Muzinich has been active in Asia in public and private credit since at least 2017 and launched its first fund for the region in 2021 with a target of USD 300m, now revised up to USD 500m.

It has received USD 450m in commitments to date, including USD 200m from DBS Bank. Tan has observed a significant increase in interest from family offices which, given the current economic uncertainty, have sought out more options that offer consistent income streams and front-ended interest payments in lieu of the lumpy distributions of private equity.

"Private credit has been the reverse of private equity in that many GPs are trying to jump on the Asia bandwagon now. We see quite a few entrants with no prior history in Asia private credit," Tan said.

"Will they ever move into the core to lower middle market segment that we focus on? Many of these GPs are deploying out of large global funds, and just looking at how they have approached US and Europe deal flow, I'm not sure it is worth their while to get involved in smaller deal sizes that are sub-USD 50m that feature in our market segment."

Even as investors tout Asian private credit's underpenetrated nature as its key draw, the quest for white space in the opportunity set persists. For example, Singapore-based EvolutionX, a platform set up with a USD 500m fund in late 2021 by Temasek Holdings and DBS, believes it is tapping into an increasingly underserved market in technology growth debt.

EvolutionX plans to make six or seven investments a year in large, often pre-IPO-stage technology companies with ticket sizes of around USD 20-USD 50m. The idea is that this is beyond the range of traditional venture debt and under the radar of middle-market players.

India, Southeast Asia, and China are the core markets, although activity in the latter has been slow. India is expected to represent more than half the fund and possibly likewise for its eventual successor vintage. There are plans to provide rupee-denominated financing as well.

To date, USD 125m has been deployed across three transactions, including API Holdings, best known as the parent of pharmacy portal PharmEasy, and B2B marketplace Udaan. Both companies are based in India and have raised more than USD 1bn in private funding.

"There are some large banks, credit funds, and investors doing this in an opportunistic way, but we are a dedicated growth debt platform to provide alternative capital to large tech companies in Asia," said Rahul Shah, a partner at EvolutionX who leads India and Southeast Asia investments.

"I expect to see a few more pools of capital being set up in the next few years because more capital is required. The tech companies in this region are growing significantly, and their needs can't be met with equity alone."

Clarifying China

Hesitancy around China is a unifying theme, even for players such as EvolutionX that are not fundraising. But even prior to the recent decline in sentiment for the market, it was always recognised as the toughest nut to crack in private credit.

Arguably the most seasoned operator in this space is Guangzhou-based Shorevest Partners, which invests across performing companies and NPLs. Shorevest is currently raising its sixth vintage with an unspecified target, although Ben Fanger, the firm's founder, notes that about half the planned commitments are locked in.

Fanger described the fundraising experience as a process of clarification. From this view, Western LPs have misinterpreted Beijing's attempts to rein in financial system risk. Policy has shifted from growth at any cost to balanced growth that prioritises stability. Blow-ups such as the default of property developer China Evergrande are merely the inevitable short-term pain in a long-term fix.

The message appears to be resonating. LPs in the new fund include US pension plans and non-China sovereign investors. Contributions have come from every geography except Africa. A final close is expected within the year.

The key to the opportunity lies in the kinds of policy shifts keeping much of the global investment industry at bay. Crackdowns on traditional bank NPLs and shadow banking providers – such as peer-to-peer lending and wealth management platforms – have ballooned the target market for private credit players.

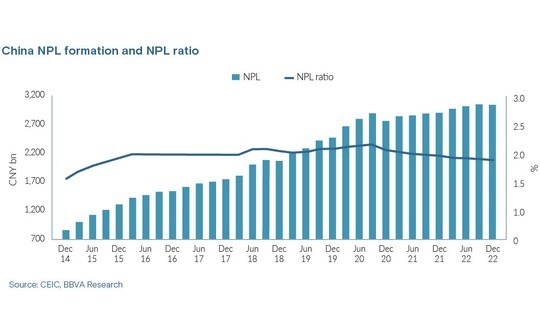

As Chinese banks have been pressed to enforce discipline around bad loans, the ratio of NPLs versus total loans has trended down from around 2% as of end-2020 to 1.6% as of end-2022, according to CEIC and BBVA Research. During this period, the total amount of NPLs disposed of by local banks scaled from about CNY 2.7trn (USD 381bn) to CNY 3trn.

As a result, China has become the largest distressed debt market in the world, topping USD 1.6trn, but there's danger in the scope of this pot. While there are presumably more winners to weed out, the weeding itself has gotten no easier.

"With NPLs, just understanding if a loan is enforceable or not in a court in China, what is involved in negotiating with corporate borrowers, whether to get rid of something or hold on for more upside – it becomes more about kicking out grenades than cherry-picking," Fanger said. "For global firms parachuting in, hiring a couple of analysts without decades of experience as scouts, it quickly becomes a minefield."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.