Value in adversity: Australia's operational challenge

With Australia poised for a rarely-seen period of economic difficulty, the operational capabilities developed by domestic private equity firms will be put to the test

Three years ago, four in every five Australian mortgages was variable rate, compared to one out of 20 in the US and one out of four in the UK. For over a decade, interest rate cuts contributed to benign conditions. And when COVID-19 took hold, the government introduced super-cheap, three-year fixed-rate loans to keep the market moving. The variable rate share slipped to three in five.

Between April 2020 and June 2021, loans amounting to AUD 188bn (USD 131bn) were issued, according to the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBI). In the coming months, they will switch back to variable rate, exposing borrowers to a string of interest rate hikes that the RBI expects to continue.

KPMG calculated that the transition would make homeowners AUD 16,500 worse off per year after tax, based on the average new residential mortgage loan size of AUD 600,000. Moreover, it is expected to be directly responsible for an AUD 20bn drop in household consumption expenditure and a one percentage point decline in GDP growth this year.

"It is the most tangible downside risk you can point to in the Australian economy. There's a lot of household debt, a lot of floating-rate mortgages, and an unusually large number of fixed-rate mortgages that are unwinding," said Anthony Kerwick, a managing director at Adamantem Capital.

"I would be surprised if it didn't have some effect, even though there are some strengths in the economy, such as low unemployment, that could counteract it a bit. As for how dramatic the effect will be, we'll have to wait and see."

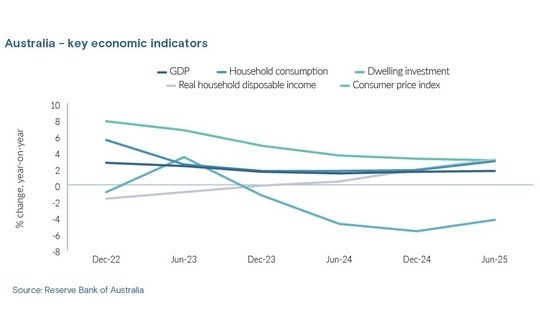

The same sense of uncertainty hangs over much of Australia's economy. The RBI admitted in its monetary policy statement earlier this month that "the path to achieving a soft landing remains narrow." It wants to curb inflation while keeping the economy on an even keel, conscious that GDP is slowing, the labour market is tight, and rising interest rates are eating into real disposable incomes.

Every projection was caveated by references to a lack of clarity – on how competing forces will influence household spending, how quickly inflation will retreat, how the global economy will evolve.

Even though most private equity investors in Australia expect a moderate downturn rather than a recession, changing conditions can shorten or lengthen value creation levers. Financial engineering and multiple expansion on exit have become less powerful, which places more onus on operational improvement. Yet some managers are still pondering their next moves in this area.

James Viles, head of the Australia private equity practice at Bain & Company, describes a client base looking for input on where to cut costs but unsure of where and when to start.

"In a downturn, you normally have workshops about how to take advantage of these conditions and buy up your weak competitors, but most people aren't in that mode," he said. "They are shrinking back into their shells looking for roadmaps for bringing out cost and becoming leaner, meaner, and more flexible. They want to be ready for growth – but not to pursue it right now."

Essential infrastructure

The speed and magnitude of operational transformation in an investment largely rest on bandwidth – the extent to which GPs can devise and execute plans internally or are willing to pay third parties for support. In Australia, like most markets around Asia, country managers have followed their global and pan-regional peers in developing specific philosophies around this aspect of value creation.

Parachuting in experienced executives or consultants with relevant expertise to work alongside management remains part of the playbook. On top of that, private equity firms are developing in-house functional capabilities that can be applied across the portfolio – to the point that some claim to be building genuine intellectual property for business transformation.

Initiatives can proliferate naturally. Viles observed that an initial focus on procurement, if successful, may prompt a manager to expand coverage into areas like digital marketing and pricing strategy. But there are more fundamental driving factors, from a recognition that the low-hanging fruit from a return perspective is diminishing to an appreciation that competition for assets is intensifying.

"It's more important than ever for GPs to maximise value from their portfolio companies, and we see investors leveraging their teams to accomplish this as much as they can," said Daniel Selikowitz, a partner at Boston Consulting Group (BCG).

"Choosing the right management team is as vital as ever, but we also see a propensity to engage external experts where needed to supplement in-house capabilities and tap into new areas of opportunity,"

Even as internal capabilities grow, that reliance on outsourced support remains. The consensus view among advisors is that local GPs are not set up to insource to the extent that they can co-sign comprehensive value-creation programmes with management teams.

Australia and New Zealand combined simply lack the depth to justify dedicated operations teams equal in scale to those of pan-regional managers – which may have a handful of people in-country and bring in additional resources as required (and those are not always internal resources).

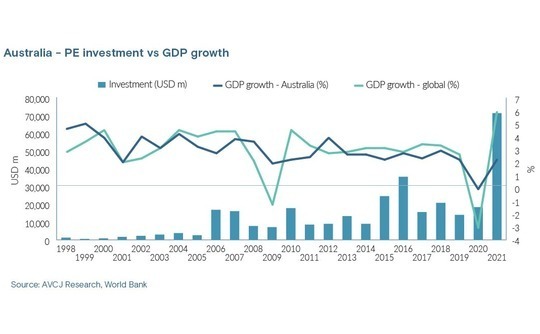

Buyout deal flow alone reached USD 117.7bn between 2022 and 2022, a threefold increase on the three years prior, according to AVCJ Research. But three-quarters of that capital was absorbed by about 20 USD 1bn-plus transactions pursued by large-scale managers. The sub-USD 500m space in 2020-2022 saw about 90 deals worth USD 14.4bn, up 20% and 50% on the three years prior.

The two largest domestic players, based on most recent fund size, are BGH Capital and Pacific Equity Partners. They have fewer than 20 active private equity investments between them.

Boots on the ground

As a spinout from TPG Capital, the BGH team replicated aspects of its former parent's operational approach. The operations group, led by the former Asia head of KKR's Capstone operations unit, comprises a dozen full-time professionals who either work in the field with specific companies or across the portfolio in functional areas like property, procurement, human capital, and technology.

There are also 11 senior advisors, mostly ex-CEO types, who sit on boards and offer input on operational and governance issues as required.

Portfolio companies pay salaries to the field operatives as long as they are in place – if they spend an extended period unattached they become a GP-level expense – and compensate functional professionals based on time spent on projects. "External consultants are more expensive, and they tell you what you need to do rather than actually do the work," said a source familiar with the firm.

What BGH has done is essentially formalise the informal rolodex networks that investors have long drawn upon. Other firms have developed their own variations on this theme.

IFM Investors, which is currently deploying a mid-market growth fund and a long-dated fund, takes a dual-strand approach. It employs a six-strong formal advisory team of functional experts – who receive a retainer from IFM plus top-ups from portfolio companies if they go full-time on specific projects – and maintains an informal network of executives with experience in different sectors.

Three years ago, the firm tried to recruit Leigh Jasper, who co-founded and led construction industry software specialist Aconex until its acquisition by Oracle, for the formal advisory team. Discussions didn't go anywhere because Jasper wanted to focus solely on construction software, but then IFM started pursuing an investment opportunity in Zuuse, which is in the same space.

"We brought him in, he helped us with the due diligence process, and he invested in the company alongside us, and now sits on the board. That's how the informal network operates," said Adrian Kerley, an executive director in IFM's private equity business. "With the formal network, it's more a case of, ‘We need you to visit this company next week to do a technology stack review."

At smaller PE firms, investment and operational responsibilities are more integrated. Anacacia Capital has an advisory council of senior executives who invest in its funds and serve on portfolio company boards. Operational legwork that isn't outsourced falls to the deal team. This means the same people are involved throughout the life of the investment, which Jeremy Samuel, Anacacia's founder, sees as an advantage when engaging owners of family businesses.

Similarly, Genesis Capital, a healthcare sector specialist that spun out from Crescent Capital Partners, has a relatively large investment team for its size because members spend up to half their time on portfolio work. There are also two functional experts covering human capital and marketing – areas where the clinical trials services businesses Genesis often backs are most likely to come up short.

"It becomes easier to have permanent in-house resources because the themes are so similar. Generalists don't have enough consistency in the domain areas to just have one person and build up that capability internally," said Chris Yoo, a partner at the firm.

Discretionary dilemma

At the furthest extreme of the market, deal-by-deal operators typically lack the balance sheet capital to develop in-house resources. Asked for a solution, Marcus Lim, a managing director at Axle Private Equity, replied: back strong management teams, invest in robust sectors.

Though intentionally glib – deal-by-deal players can rely on outsourced expertise – the response sheds some light on how Australian GPs think about sectoral exposure and downside risk.

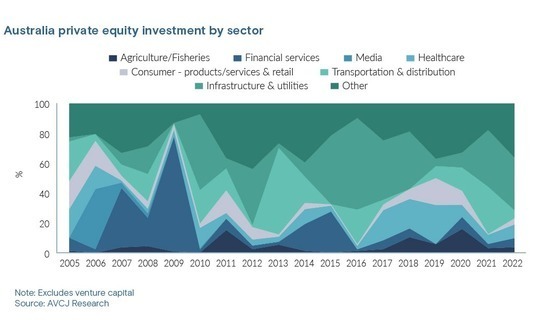

While the country never slipped into recession following the global financial crisis, some investments in cyclically volatile segments performed poorly. In 2006-2007, media and consumer (spanning retail as well as consumer products and services) together accounted for 32% of all deal flow excluding VC. In 2021-2022, consumer and media were 2% and 0.2%, displaced by more defensive assets.

"It wasn't where the action was at the time, so we thought we had an opportunity to invest in a business at an attractive valuation, and when the economic cycle turns, it will come to be seen as a safe and consistent asset – the sort of thing that is recession-proof," said Kerwick.

Adamantem recently invested in Retail Zoo, an operator of fast-casual restaurants and juice bars that might be regarded as far more exposed to the vicissitudes of consumer demand. The firm was confident enough in the management plan to look beyond an expected near-term decline in spending, driven partially but not wholly by the mortgage adjustments, and focus on the long term.

At the same time, the line between discretionary and non-discretionary can be blurred. The RBI is projecting that GDP growth and household consumption to decelerate over the course of this year and not rebound until the end of 2024. Investors believe the likes of apparel, cars, and household goods will be hit hard, but other areas may not suffer.

Axle owns a 180-outlet carwash business and went looking for data points from the post-global financial crisis period in the US. There was no meaningful downturn. BGH owns cinema chains and amusement parks: the former perform well during soft economic periods because they are a low-cost source of entertainment; the latter are benefiting from a domestic travel boom.

"Sometimes the impact on discretionary spending is not what you would expect. For instance, in prior downturns, we have seen at least 25% of consumers display a willingness to trade up across a diverse array of categories. They might spend less on going out for dinner at a restaurant, but will treat themselves to more expensive fresh produce or personal care products at home," said BCG's Selikowitz.

"If a company is highly exposed, it's important to thoughtfully pull levers around pricing, promotion, and loyalty programmes in a way that maintains footfall and relevance during the downturn, while driving down cost to weather exogenous shocks."

Stepping up

Some of these levers started being pulled a year ago in response to inflationary pressure. Yoo said that Genesis helped portfolio companies offset rising wage costs through analytics-driven efficiency and productivity initiatives. Viles noted that several GPs sought to address cost headwinds by leveraging portfolio scale and synergies. Procurement was the most logical starting point.

Supply chain management and employee recruitment and retention – amid severe labour shortages – have been top-of-mind for many managers. Looking ahead, references to the importance of having a strong capital structure and the virtues of pricing discipline are frequently made.

According to Timo Schmid, who leads the Australia private equity performance improvement practice at Alvarez & Marsal, there has been a step change in the inquiries he's received from managers in the past year. The reactive mindset underpinned by pandemic-related business continuity issues has been replaced by a desire to get ahead of impending economic challenges.

"Operating teams want a holistic view, and they want to respond in a more systematic way," he said. "We are getting requests for downturn management offices. They are asking, ‘What do I need to do upfront if I invest in a company and need to deal with a range of functional topics for a range of 12-24 months? What do I need to plan for? What do I need to invest in during my first 500 days?'"

One of Schmid's concerns is the lack of experience in an Australian private equity industry largely populated by professionals who haven't seen a meaningful downturn – it leaves "a gap between seeing the iceberg coming and having the capabilities to bring the ship around."

There are myriad risks, not least that private equity investors become too defensive in the face of adversity. This is manifested in an unwillingness to invest in growth that could position portfolio companies favourably coming out of the downturn or in a failure to recognise where inflation might be easing and realise benefits in areas that might have been pain points a year ago.

Indeed, David Odgers, an executive director at IFM who previously served as an operating partner at Bain Capital, describes operational improvement as long-term agenda: it responds to macroeconomic developments but is not defined or unnecessarily distracted by them.

"With monthly board meetings, steering committees, engagement surveys, strategic planning processes and so forth, you should be nimble enough to adapt to what is happening on the outside world as well as to what is happening on the inside," he said.

"You must consider the external environment and weigh that into your thinking, but the value creation approach doesn't change; maybe the emphasis changes based on what moves into the ‘urgent and important' bucket."

In this context, the economic uncertainty that discourages aggressive action could be interpreted as a positive. Adrian Loader, a partner at Allegro, observes that deciding whether to push ahead with operational initiatives is very situation-specific, yet it is influenced by macro-level planning – and for all the plans being drawn up, no one really knows how different scenarios will play out.

"Since 2020, volatility has been the main game. Shocks are coming from everywhere, so we must be agile and sharp," he said. "The only thing we can really be certain about is that volatility will continue, from an operational point of view and potentially from a financial point of view."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.