Labour shortages: Tales from north and south

Australia and Japan are facing extreme labour shortages. In the former, GPs can survive on policy support and emergency manoeuvres. In the latter, fundamental strategy shifts are a more immediate imperative

Suffering the most acute labour shortages in the region does not seem to have rattled private equity in Australia and Japan. Both markets have enjoyed robust fundraising in recent years, with deployment continuing apace. While portfolio companies are feeling the pressure, there's little expectation it will translate into weaker returns.

In Australia, this is partially attributed to investors benefiting from relatively low entry multiples in the most impacted industries. In Japan, there is the idea that rising labour costs are a perennial factor baked into deal valuations and therefore exits. Part of it is rethinking human resources strategy. Part is old-fashioned belt-tightening.

About 45% of Australian companies have reported having difficulty finding suitable staff, according to government data. That number is currently around 50% in Japan, according to Teikoku Databank.

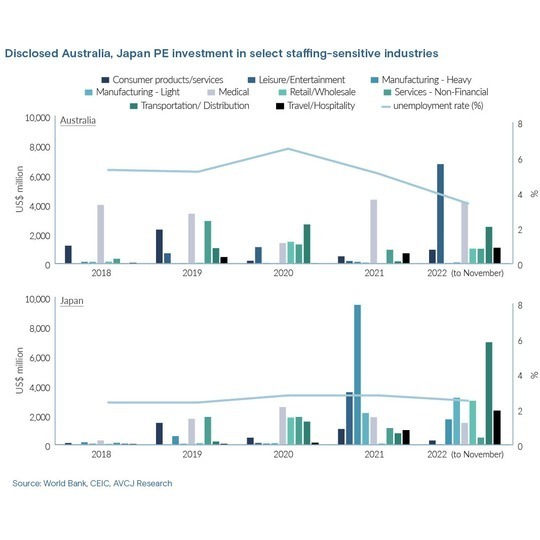

The unemployment rate is a more convenient indicator of labour availability. It fell sharply in Australia in 2022 from 5.1% to 3.4%, straining operations in PE hotspots such as consumer and medical services, and leisure and entertainment. Japan's unemployment rate, in freefall for a decade, stands at 2.5%. Areas of weakness include consumer and medical services, manufacturing and, increasingly, retail and hospitality.

Labour woes in Australia can be squarely blamed on COVID-19 and as such have come with optimism that the effects will be temporary. The country's economic hibernation and border closures during 2020 and 2021 prompted many indispensable foreign workers and student visa holders to return to their home countries. There was a net loss of 88,800 migrant workers during this period, official data show.

Amidst a rapid reopening in 2022, immigration infrastructure has been slow to get back into gear and travel expenses have remained high. Long-haul airfares to Australia are still often 3x pre-pandemic levels, reinforcing the market's remoteness.

Uptake of automation has been historically slow and has not accelerated under COVID-19, with most investors citing survival-mode budgets and cultural resistance to changing consumer behaviour.

"If you surveyed our CEOs, they could sell more if they could get enough people – and that's unique. In most surveys going back in time, the biggest question was how do I sell more? Where unemployment rates are now, you just can't get people, so you can't sell more even though the demand is there," said Fay Bou, a partner at Sydney-based Allegro Funds.

"Compounding that is the COVID disruption where you just can't get a consistent workforce. Hopefully, this supposed next wave of COVID doesn't create more problems. We're very cognizant of that."

In Japan, the pandemic is merely an aggravator of more important – and better understood – secular trends. The working population is decreasing, the rate of working to non-working people is declining, and job-to-applicant ratios are increasing. Businesses with large staffing needs historically able to absorb the costs of outbidding their competitors for labour are now finding there is simply no one to hire.

The phenomenon has spread from skilled to unskilled labour at a time when currency depreciation has eroded Japan's appeal for foreign workers. Cultural obstacles to immigration are myriad but best exemplified by hierarchical professional associations where opportunities are seniority-based and outsiders cannot easily integrate. Automation is a long-term and incomplete solution.

"The number of high school and university graduates is dropping every year because of the demographics. That means this war for talent is structural, it's going to intensify, and the quick fixes that you have in more immigrant-friendly countries, we just don't have here," said Jesper Koll, senior Japan adviser at WisdomTree Investments.

"If you're having problems today hiring workers, trust me, next year is going to be twice as difficult."

Feeling the pinch

Total private equity and venture capital investment in Australia fell 31% during 2022 to USD 48.9bn, but this is still significantly higher than the annual average of USD 22.1bn during the five years prior to the pandemic. Although widely seen as a natural correction, the slowdown could be partially attributed to labour shortages, at least in the sense that due diligence services are more difficult to source.

"The accounting firms have been struggling with [labour issues], and we've seen that in terms of the costs of the audits and the delays of the audits," said Simon Moore, a senior partner at Colinton Capital Partners, who was previously Australia country head at The Carlyle Group.

"The ASIC [Australian Securities and Investments Commission] has given extensions on the filing of financial statements of public and private companies. It's just an acknowledgement that there's just not enough arms and legs to get the work done, unfortunately."

Colinton has several portfolio companies in industrial services that are feeling the pinch, which has been exacerbated by a post-pandemic boom in demand. They include an office cleaning services provider, Dimeo, whose workforce is typically two-thirds foreign student visa holders, and a car repair company, AMA Group, that relies significantly on foreign mechanics.

AMA offered an opportunity to be more proactive. Colinton has enjoyed some success engaging former employees who have left the country, although all rehires must join a queue to get a visa. The current backlog is estimated at around 1m visas.

More ambitiously, the private equity firm set up a three-year training course that has facilitated around 300 apprenticeships in the past year. This is as much about retention as developing new talent, the idea being that improved career pathways improve loyalty. But it's a long-term solution that has yet to bear tangible results.

In the meantime, wages have increased across the market. Pay hikes of 5% to 7% – versus a historical norm of 2% or 3% – were common in 2022 and reflected in the portfolios of investors such as Quadrant Private Equity.

Alex Eady, a managing partner at the private equity firm, said, however, that stable demand for goods and services has allowed his firm to pass on these costs to end customers. This is a key initiative for Quadrant, not limited to salary increases. In the case of top management at risk of poaching, sweeteners have included equity ownership programmes and other specific payments.

The demand for goods and services making it possible to absorb these costs is not expected to persist in the immediate macro outlook. But that gloom appears to be increasing the value of job security and thereby stabilising workforces. Meanwhile, a return to immigration normalcy could begin as early as April, when the government is expected to clear its backlog of visa applications.

"Our view is that the demand profile for the consumer is likely to ease in the new year. Employees see that the interest rates on their mortgages are going up," Eady said. "They're seeing less certainty in their environment, and that's leading them to value employment rather than seeking a pay rise. The pendulum is swinging some way to the employer."

Lessons learned?

If Australia's labour troubles indeed last for merely half a fund cycle, there is arguably some risk that the industry will escape the episode without having to learn any lessons.

Moore said he believes it will force GPs to double down on labour substitutes such as robotics as well as employee training and retention tools, including development programmes, productivity tied to pay, benefit plans, and broader equity pools. Eady said a company's capacity to attract and retain labour will be more prominent due diligence factors going forward.

"For active managers, the recent talent shortages could be a catalyst for longer-term innovations such as micro-credentialling, a broader definition of diversity in hiring strategies, utilising the expertise of migrants already in Australia, and looking at opportunities for latter-stage tertiary students," said Australian Investment Council CEO Navleen Prasad.

The picture is more complicated in Japan. The relentlessness and existential nature of population decline has no systemic parallel in Australia, and there is less optimism around policy fixes in areas like immigration. To some extent, the labour question is shrugged off as a longstanding issue and part of business as usual. But there are also signs of increasing urgency.

Last November, the Japan Business Federation, also known as Keidanren, recommended its members increase wages in line with core consumer prices, which climbed 3.7% that month to a 41-year high. The organisation has historically knocked back trade union demands for 1% wage increases. Now, the unions are calling for 5%, which Keidanren has labelled "ambitious" but did not dismiss.

In an extreme example of the development, clothing brand Uniqlo said this month it would raise wages by up to 40%. In a marked departure from the Australian scenario, these costs – in combination with inflated utilities, supply chain, and workforce retention expenses – appear to be difficult for companies to pass on to customers, even when demand is high.

Part of the problem is the fact that many staffing-reliant industries in Japan remain highly fragmented, which makes companies reluctant to increase prices and undermine their ability to compete. For B2B companies, much will depend on the frequency of contract renegotiation.

"If you don't have an annual operating model with your customer, it's very hard to say in year five, ‘By the way, now we would like to discuss a price change,'" said Jim Verbeeten, a partner at Bain & Company. "A pharmaceutical contract manufacturer, for example, would have long-duration contracts and the customers are sticky, but you just don't have the annual rhythm of negotiating prices."

Verbeeten advises Japanese GPs to lean into the labour issue, targeting investments in businesses that intermediate talent, facilitate automation, and provide worker migration services. Companies with enough scale to invest meaningfully in labour-saving technologies, employee satisfaction, and direct recruiting are preferred.

Small companies needn't be doomed to rely on recruiting agents, however, especially if they have international ambitions. Fiducia, a growth-stage investor set up in 2020 by Tokihiko Shimizu, previously head of a government-linked private equity program for Japan Post Bank, offers a case in point.

One of the firm's first investments was the purchase of a 30% stake in non-fried potato chip maker Terra Foods. Terra has a small production facility with only about 15 employees in the remote Oita region but still managed to bring five Vietnamese factory workers to the site, each of whom had to learn Japanese.

More importantly, Fiducia deployed its co-founding partner Takumi Shibata as CEO of Terra. Shibata was previously CEO of Nomura Asset Management and Nikko Asset Management, as well as COO of Nomura Group and Europe CEO of Nomura International.

Targeting expansion in the US and Europe, Shibata helped build out a new management team of Japanese professionals already living and working in California. This coincided with a partnership with a banana plantation operator in Indonesia, where there are plans to move into non-fried banana chips and leverage a more welcoming labour environment with an in-country factory.

"The kinds of people we need in management for our portfolio companies must have management skills, English skills, and technology knowledge and experience. There are very few people who satisfy all three of these criteria in Japan. But if the business is expanding abroad, you can collaborate with foreign companies," Shimizu said.

Inclusion agenda

The internationalisation of Japan PE also represents a labour solution in terms of meeting global standards in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) compliance. Significant upside on this front includes the opportunity to bring more women into higher-quality jobs. Women represent 70% of minimum wage jobs in Japan (60% in Australia) and 13% of management positions (35% in Australia).

Nevertheless, fewer than 20 GPs are signatories of the UN's Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) network, and only one mainstream PE investor – NSSK – is a signatory to the International Finance Corporation's Operating Principles for Impact Investment.

"General labour shortage is not a problem for companies that have progressive ESG policies focused on making the workplace a better environment to work in, clear career paths, flexible work schedules, and accommodating policies for working parents," said Jun Tsusaka, CEO of NSSK.

"Those companies that are not viewed as attractive places to work will find it difficult to grow and keep up service levels. But the industry is significantly behind in adopting ESG practices – although the intent is there."

The intent is easily detected in anecdotal feedback from the industry. Diversity, inclusion, and employee benefits from childcare to career development options are becoming as buzzy in Japan PE as digital transformation. This has come with a recognition that work-life balance rather than the latest technology is the deciding factor in attracting top talent, technical or otherwise.

WisdomTree's Koll points to the nursing industry as an example of how an underinvestment in human capital, combined with a weak yen, is exacerbating an already critical labour shortage by increasing workers' mobility.

He describes a Tokyo hospital that lost only three nurses to global competitors in the past decade but haemorrhaged 12 toward the end of 2022. Where did they go? Australia, with about triple the salary in yen terms. The key takeaway is that the power has shifted from employer to employee, and unlike in Australia, it's not going back.

"You still have plenty of zombie companies and underemployed people. Saying they're not good enough is a bad excuse. You have to take people who are average or lower performers and train them to give them opportunities," Koll said.

"If you can't educate your workforce and upgrade your skillset, then you've got a management problem, not a demographics problem."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.