Taking PE in-house: Less limited partners

Institutional investors continue to pursue more active roles in private equity, even as a souring macro backdrop makes the game harder to play. Talent is always the key variable

What are the implications of a more difficult macro environment for the relationships between large LPs and their portfolio GPs? First and foremost, it means there will be fewer of them, which suggests deeper, longer-term engagements. But it also means LPs will seek greater flexibility in how they invest – the kind of flexibility more typically associated with GPs.

"Big institutional investors are hesitating and are being a lot more selective about new commitments to private equity funds in light of market uncertainty. But when it comes to direct opportunities, it's a lot more fluid," observed Alex Boulton, a Singapore-based partner at Bain & Company.

"If they find something they're willing to put money to work in, they will. And there's capital on the balance sheet to do that. Taking on a new five to 10-year LP commitment takes a lot more forward planning, especially when it comes to your cash flow and asset allocation."

The effect here is a seeming contradiction in terms of how investors take on a more conservative posture. Even as they pull back on fund commitments, direct exposures are vigorously pursued, often in categories where valuations are difficult to nail down. And there are reasons to believe the phenomenon is intensifying as macro pressures mount.

The number of direct investments by sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) reached a record 429 in 2021, up 60% against the prior five-year average, according to the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds. The amount for 2021 was a five-year high of USD 71.6bn, doubling the 2019 total. Asia was the most aggressively pursued geography in consumer and closely trailed the Americas in tech.

Singapore's GIC has been among the most active players in this trend, particularly in light of a string of hospital deals. Last year, it invested USD 180m in Malaysia's Sunway Healthcare and USD 204m in Vietnam's Vinmec among others.

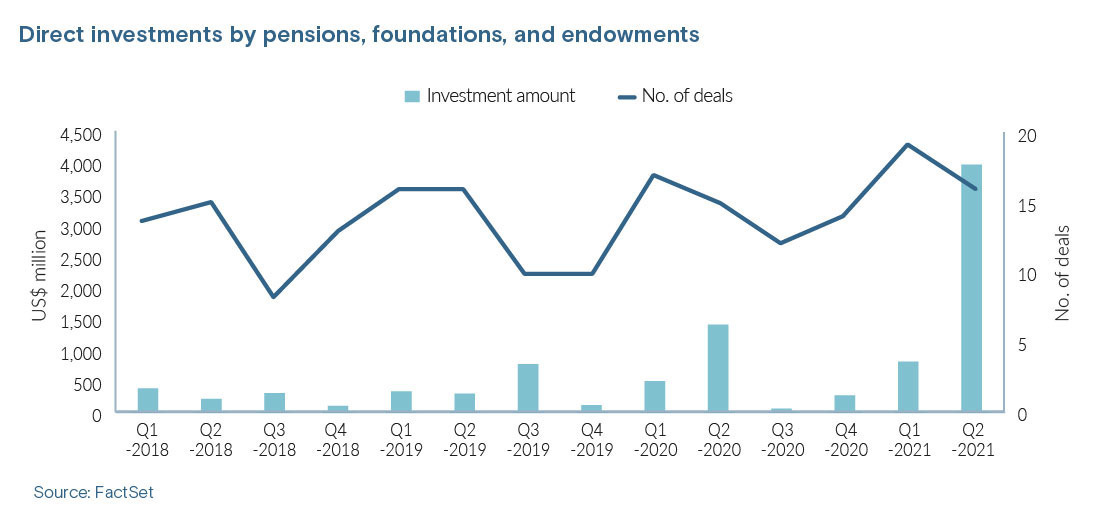

Global pensions, foundations, and endowments have similarly mobilised, deploying USD 4bn in the second quarter of 2021, according to FactSet. That's more than the prior six quarters combined. Standout moves in Asia included Robert Bosch and Novo Holdings co-leading rounds of USD 500m and USD 200m, respectively, for Chinese autonomous driving supplier Momenta and Singapore's Esco Lifesciences.

In August, Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan (OTPP) took a majority stake in Sahyadri Hospitals, which was its first control private equity buyout in India, and its fourth major investment in the country over the prior 12 months. The pension plan followed up with its debut co-control deal in Asia, picking up a stake in China-headquartered packaging manufacturing company GPA Global.

People power

The biggest challenge for LPs going direct is maintaining a program over the long term by retaining and multiplying the relevant talent. But OTPP appears to be leveraging the current frenzy in LP directs to achieve critical mass in Asia: it opened an India office in September and now has more than 65 employees in the region. Could a global downturn send more private equity talent in this direction?

"For the past few years, the macro environment has been very good, everyone has struggled to hire PE talent, even our GPs. Now that that environment is changing, we don't know what's going to happen," said Eric Lang, senior managing director for private markets at Teacher Retirement System of Texas (TRS). "It's possible that heading into some choppy waters economically might make it easier to hire and retain people."

TRS, like much of the pension industry, has struggled to hold on to investment professionals in recent years. It has trained people up only to lose them mid-career, primarily for compensation reasons.

Still, there are murmurs that a slowdown in M&A markets is translating into staff cuts at investment banks, which could send more talent toward institutional investors. In a rockier macro backdrop with continued high competition and a lot of dry powder, operational abilities will be most in demand.

Whether or not they can be procured will decide much about GP-LP dynamics. LPs that can build out more internal PE capabilities will have different priorities in manager selection for fund commitments. In relative terms, it will be less about identifying the best performers in pure economic or impact terms and more about filling holes in an existing expertise set.

British Columbia Investment (BCI) is among the pensions tracking a rebound. In the past three years, its PE team has been trimmed from 52 to 42 people but rebounded to 50 in the past nine months. The goal was to reach 65, adding 10 as part of a New York rollout. The target for the expansion office has now doubled as M&A layoffs in the city fuel recruitment.

For BCI, the traction is confirmation that there is no talent shortage – it's just a matter of identifying the right style of talent for the LP universe. These are usually older people, who prioritise work-life balance. This talent pool is also attracted to variety in investment remit: large and small deals, a global geographic lens, and more opportunity to work across strategies.

BCI provides an apt example for the idea of LPs internalising PE activities as a secular expansion. As new divisions and strategies are added, headcount will undulate, perhaps especially in terms of the top talent. But rare is it to see an institutional investor consciously scale down its direct investment capacity after the strategy has been confirmed as a long-term ambition.

Denominator disruption

The pension plan is also in the relatively unique position of being able to accelerate its deployment pacing in private equity at a time when most of its peers are concerned about overallocation amidst more frequent capital calls class and drops in public market valuations.

The private equity allocation is currently around 12.5% against a target of 15%, leaving significant room for increased investment across direct deals, co-investments, and funds. The opportunity is largely thanks to a concerted selling effort on the secondary market, including some USD 4bn in fund positions across the past few years, and almost USD 5bn in direct deals last year alone.

"You don't want to be in a position where you have to sell in a down market. That's the worst time to do it. But there's an interesting dynamic in the secondaries market right now. For the past five years, there's been much more demand than supply, and today, there's much more supply than demand," said Jim Pittman, global head of private equity at BCI.

"The public markets are down 20%, and GPs are between zero and minus 3%. So, to some degree, if you can sell funds today and get a 15% discount, you're probably net-net positive – if you believe where the public markets are."

Pittman estimates offhandedly that as much as 70% of pension funds are experiencing the denominator effect. They must now consider fundamental questions about their level of private equity exposure and whether they have the resources to play in that space long term.

With previously robust exit activity drying up rapidly around April, GPs are looking for near-term liquidity to alleviate the pain. Several LPs AVCJ contacted for this story suggested managers were looking to sell 30-40% stakes in companies to get distributions back on track. This could create an opening for LPs to re-allocate to PE over the next six to 12 months, but it remains a marginal trend and a theoretical fix.

Meanwhile, institutional investors could have fewer dollars to deploy in 2023. The wave of GPs coming back to market in shorter cycles in recent quarters has prompted many LPs – especially in North America – to begin chewing into their 2023 allocations as early as last April.

The more recent slowdown in fundraising has curbed this effect to some extent, but it is ongoing and raises the question of when 2024 budgets will be tapped. Allocation models have been under particular pressure in the venture and tech space, where access to the best managers is considered so competitive, re-ups are hard to deny.

Overlaying all these considerations is the idea that fund commitments must remain consistent because they are likely to be invested 3-4 years down the track and it is impossible to predict market undulations. Direct investments provide more options in terms of timing, but erratic valuations have proven a complicating factor.

Chris Ailman, CIO of California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS), observes that in the next six months, lower company valuations could create an enticing moment to put money to work in direct deals. But this would remain a difficult decision for LPs still overweight on private equity.

"Any pacing model is simply trying to predict the future, which is therefore flawed," Ailman said. "I've been adjusting and refining pacing models since 1996, and I can tell you for a fact that it's all art, as much as it feels like science, simply because you're trying to make assumptions about the future and how people will react to it."

Timing a ramp-up in direct investments could be especially risky in large deals that will require currently difficult-to-access debt. Ailman noted that the largest co-investments in the run up to the global financial crisis turned out to be the worst. "It's no secret that when private equity does something big, it's usually not going to result in anything good," he added.

Co-investment conundrum

Nevertheless, larger LPs across geographies and organisation types appear unanimous in their desire to amplify their principal investment programmes in the years to come. The most fundamental impacts on GP-LP relations will revolve around demand for co-investment, which is likely to result in larger checks and smaller LP bases.

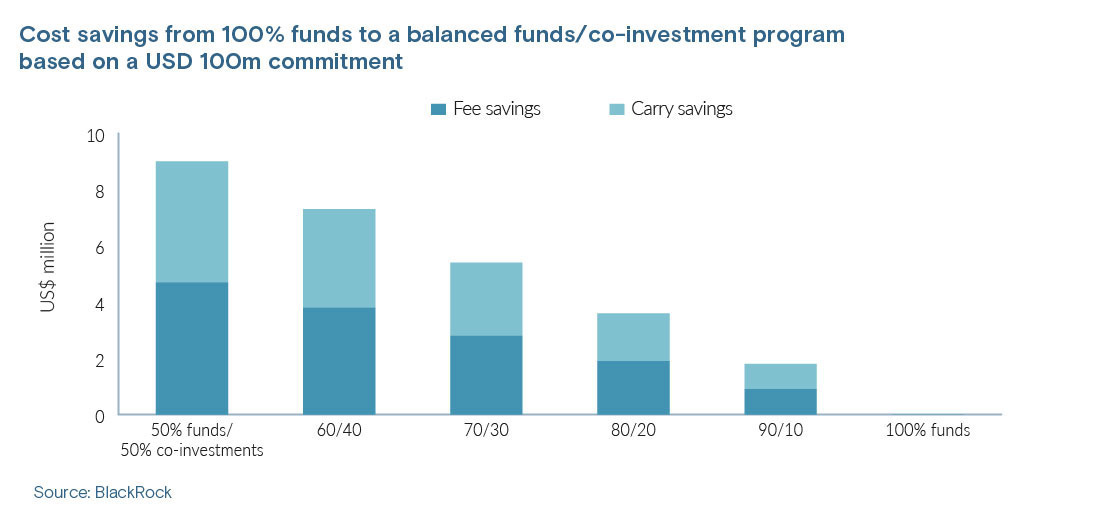

Fees remain the core motivator for internalising this capacity. The prevailing assumption is that the economic benefits of increasing co-invest versus fund commitments begin to become significant around a 75:25 ratio. Beyond that, the challenge of maintaining a significantly robust directs team suggests there could be long-term diminishing returns.

A study by BlackRock helps explain why an industry push toward a balanced PE programme (50:50 co-invest and funds) persists. Assuming a gross deal level return of 2x, fund management fees of 2%, co-invest fees of 0.75%, and 20% deal-by-deal carry, a balanced PE programme will deliver LPs USD 9m in fee and carry savings on a USD 100m deal versus USD 3.6m in fee and carry savings in a 80:20 split.

"Depending on the gross IRR, you're saving 500-700 basis points if you're not paying fees. But we also know that if you get your selection wrong, that can evaporate very quickly because the dispersion of returns in PE is the widest of any asset class," said Stephen Whatmore, head of private capital at QIC, an Australian SWF.

"So, it's not just about fees – it's about using our brand and capabilities to secure quality access. That looked easy for the last five years because everybody was making money, but now we're in a market where people are going to see that it's more challenging than they thought."

SWFs' ultimate motivations to internalise PE capacities often parallel pensions in terms of building and safeguarding public wealth. They are also similar in their ability to do direct investment more consistently through cycles without constraints around the size of cheques or stakes. For example, all GIC's hospital investments during the pandemic have been minority stakes.

Strategic agendas

Among the largest institutional investors, SWFs have historically displayed the clearest strategic agenda in terms of private equity activity. But other types of institutions are taking on this profile as well.

Kimberly Kim, head of the financial institutions group for Asia Pacific at BlackRock, said her firm was tracking a significant uptick in demand among insurers for private market exposures for strategic reasons, especially around decarbonisation. This includes a greater appetite for co-investment.

In a survey covering 370 insurance companies – one-third of them based in Asia – representing USD 28trn in assets under management, respondents said they planned to increase their allocation to private markets by 3% on average over the next two years.

Private equity, typically a prohibitively expensive asset class for insurers for regulatory reasons, was the second most attractive area to increase allocations, with 48% of respondents expecting to lift their exposure in the next 12-24 months. Commodities was in first place at 55%.

Insurers will need to make various internal changes to accommodate this shift, which will have implications on their relations with managers. They will need to be nimbler and more tactical, use more data analytics in-house, and enhance capabilities around leveraging external managers.

GPs, meanwhile, will increasingly need to consider the specific needs of insurers, including an understanding of asset and liability management requirements and an arguably greater climate focus versus other LPs. BlackRock, for its part, has coded local insurance regulation into its Aladdin portfolio management software to provide more customised service.

"In terms of GP-LP dynamics, we're going to see a more partnership-based approach and deeper relationships between the two parties. And a lot of that will really depend on the strategic objectives of the insurance company," Kim said.

"Based on our observations, increasing interest in exploring co-investment opportunities is not just about economic benefits – there's a strategic motivation for getting into that space."

From the GP perspective, these developments mount further evidence that co-investment is no longer a special arrangement limited to anchor LPs. The trend appears likely to create the most disruption in the middle market, where managers could be more susceptible to being pushed out of their comfort zones.

"It means either GPs have to punch above their weight into a new deal size – selectively where they can put a lot of money to work – or they need to do more deals, which creates challenges," said Bain's Boulton.

"You don't want your LPs to walk away with only the big, risky deals, where you lever them up with co-investment. You need to be thoughtful about how you're going to offer co-investment and do it in a consistent way that delivers value."

Sowing seeds

The smaller end of the market is another story, especially since there is much cross-over between the needs of boutique managers and LPs trying to internalise private equity skillsets for the first time. This can lead to some creative approaches to PE internalisation and uncommonly intimate partnerships.

Sun Hung Kai & Co is the standout example in Asia. A stalwart of capital markets services since the 1960s, the Hong Kong-based investor began transitioning into alternatives around 2015. To a significant degree, onboarding knowhow has been a matter of seeding emerging managers.

The strategy appears to have given Sun Hung Kai an unlikely confidence in high-risk domains. For example, there have been direct investments in bleeding edge models such as a virtual real estate platform (Hong Kong's Sandbox) and a digital assets bank active in web3 concepts (Singapore's Sygnum). It's worth noting that one of the managers Sun Hung Kai has seeded is a crypto specialist.

The group positions this GP portfolio as a one-stop alternatives platform for its clients, so helping its constituent investors grow is considered a clear win-win. As part of the effort, Marcella Lui was brought in earlier this year as head of funds distribution and investment solutions to help these managers tap into different investor segments in fundraising.

"That's not easy in today's market, which is pretty much in wait-and-see mode. But external investors appreciate the alignment of interest between Sun Hung Kai and these managers," Lui said. "The breadth and depth of this alternatives offering – and our ability to work with the managers – is also really compelling for investors who are looking for something bespoke."

The largest of these relationships is ActusRayPartners European Alpha Fund, a hedge manager that has grown from USD 20m to USD 300m in assets under management since Sun Hung Kai's investment. The only pure private equity player is E15 VC. The GP received USD 15m to anchor its second fund, which closed on USD 32m.

E15 VC is also based in Hong Kong and uses Sun Hung Kai's office space as headquarters. This has facilitated significant cross-pollination between teams. Sometimes E15 goes to professionals covering other asset classes within Sun Hung Kai for support with a specific query. Sometimes, it's the other way around.

Not every seeded manager takes up residence in the office, and they do not all have close relationships with Sun Hung Kai. But the option is there; Lui notes that there is still available space although she emphasises such arrangements are offered on a selective basis.

"You see that in pitchbooks about why you should use [a certain investor platform], but I hadn't actually lived it and seen how it works in real life, where you don't force it. Everyone has their doors, but they're glass doors," said Ted Lee, CEO of E15 and formerly a managing director at both Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) and The Blackstone Group.

"I know that if there's something complicated that needs to be discussed, there's a guy a two-minute walk away, who I can talk to. No special agenda necessary – it's just peers. There's real value in that."

Despite the intimacy of this approach, Sun Hung Kai fashions itself as having light touch with managers. To this end, it prefers a revenue-share model – rather than taking equity stakes – while offering support such as warehousing facilities to expedite deals while fund paperwork is still in process.

"If you're an LP, a great way of boosting returns is simply having a good portfolio and being able to do co-investments. And what better way to do that than constantly interacting with your managers and having them on site?" said Philip Liang, E15's managing partner.

"You're clearly going to have the first access to deals. You're going to know the most about them, the upside and downside. The benefits to co-investment are huge because we know we have a partner that's going to do a follow-on investment, and they get to pick some of our better companies and get higher exposure, increasing their returns. It makes a ton of sense."

Going too big?

The Australian superannuation space helps illustrate the difficulty of scaling this kind of approach. In private equity, internalisation generally means a smaller number of larger-size fund commitments plus co-investment alongside portfolio managers.

Seeking to go large has resulted in a strong tendency to prefer the blunt tools of direct investing with in-house teams and more aggressive co-invest terms. In certain situations, super funds are known to demand USD 3 of co-investment for every USD 1 of fund commitment. They have significant negotiating leverage over local managers.

"Some of the old-school PE guys in Australia really don't want to give up co-invest, but you have to either give us a very material fee rate or co-invest, or both. The reality is, we have no requirement to partner with anyone in Australia if we don't want to," said one super fund manager. "You can go off to the US, and they'll ask who your local anchors are. If you don't have any, that's bad."

Part of the super fund equation is the idea that the industry is further down the conservative end of the spectrum than much of the pension fund universe. For the most part, there is an acknowledgement that Australian superannuation is not ready to take on the level of complexity in commercial decision-making required to do PE alone. Most funds want more direct ownership, but they want to do it with partners.

There are numerous local challenges, not least currency depreciation against the US dollar, which can exacerbate the denominator effect for those with large international portfolios.

More important is the notion that super funds are at a disadvantage to their Canadian counterparts in terms of regulatory requirements around budgeting for staff, which keeps the talent hurdle high. Another super fund manager said it has been in talks with the likes of GIC and Canadian pension plans about adopting a more cooperative approach with GPs, but people remain the sticking point.

"We see the Canadians as 10 years ahead of us. They partner with GPs rather than do everything internally, and that's where we would like to be," said the second super fund manager, flagging a need to reduce manager fees.

"Until the board gets comfortable paying the levels that the Canadians pay, it will be difficult to attract and retain the right talent. AustralianSuper has lots of people, and it is doing more internalisation, but it's still mostly a hybrid model where they partner with managers."

The talent question is set to become even more critical as deep operational capabilities become indispensable. And there is concern that in fee-sensitive jurisdictions such as Australia, programmes are being launched without the appropriate skills in place. At some point, the drive to internalise private equity may backfire and bring the industry debate more into the open.

The strongest brand names will have a natural advantage in terms of recruitment, though only where there is an existing PE programme. Entrepreneurial inroads such as seeding emerging managers will not serve the bulk of large institutions with intentions to scale indefinitely. But there are few other options for going from zero to one.

"Those that do it have done it from the start. I haven't really seen anyone new doing it. They ask about it, and some say they do it, but they rarely do," said David Brown, Asia Pacific deals leader for PwC, referring to institutional investors setting up new PE programmes.

"If you're setting something up from scratch, you're going to need to headhunt from established GPs, and you're going to need that kind of expertise and operational capability because you can no longer just rely on things being more valuable in time. That's going to cost you a lot of money, and it can be difficult and risky for many of these institutional investors to justify that."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.