GP selection: Discriminating customers

Sizeable LPs are hardening their criteria for fund commitments in reaction to a tougher investing environment. But going with fewer, deeper relationships is an uphill climb

LPs have a long list of reasons to believe their job selecting GPs is getting more difficult. Much of this can be blamed on opportunism around COVID-19 dislocation and the rapid deceleration amidst downturn expectations in more recent months. Overarching it all is the idea that higher employee turnover within fund managers as a result of these shifts has elevated the need to re-test relationships.

The greater uncertainty has slowed pacing of commitments and raised the bar in terms of transparency, sustainability, and sweeteners such as co-investment. At the same time, LPs say they're seeing less continuity in returns, which increases the relative weight of less measurable factors around process, team, philosophy, and deal flow. GP selection was always a judgment call, but now it's foggier. Or is it?

"Institutional investors say it's getting harder to pick GPs, but I think the last several years have been hard and it's about to get a lot easier because the tide is going out and they'll see who's wearing bathers and who's not," said Steve Byrom, former head of private equity at Australia's Future Fund, who now runs institutional advisory firm Potentum Partners.

"The challenge is that LPs haven't needed to figure out what quality looks like, and it's no longer good enough if GPs have had high performance – it's about what drove that performance and can that be sustained in this new environment. What's more, there's little consensus among LPs on what quality looks like."

Quality is an ethereal concept, with most attempts to flesh it out evoking important but difficult-to-validate virtues such as experience through cycles and deep operational toolkits. The first step is often to weed out the hallmarks of momentum investing, including implied strengths around timing trends and a reliance on leverage in a low-interest rate environment.

Increasingly, this process also means demanding evidence of a repeatable formula for post-acquisition value creation, whether that involves in-house or third-party resources, with data-driven performance benchmarking backed up by qualitative interviewing on specific operational contributions.

The imperative to seek out value-add capacity in GPs has only intensified as the impact of its absence comes into focus. PwC demonstrated this in dramatic style with new research suggesting that, on average, doing a deal destroys value in terms of total annual shareholder returns.

The study found that 53% of buyers and 57% of sellers in M&A transactions globally underperformed their peers (owners that did not do a deal) during the 24-month period following the deal. Private equity historically represents a minority of this activity, but that's on track to change, with PE involvement in Asian M&A said to have tripled to 40% of all deals during the past 16 years.

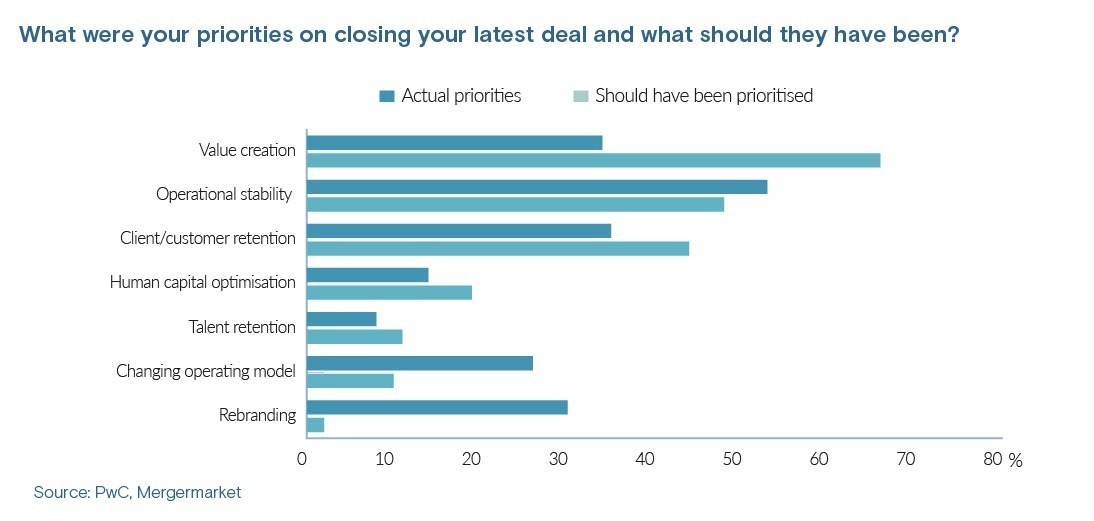

A survey conducted by PwC and Mergermarket, AVCJ's sister title, found that corporate executives experienced significant buyer's remorse, much of it doubtlessly driven by private equity. Only 34% said value creation was a priority at the time of acquisition, although 66% said it should have been. In Asia, these figures were 29% and 66%.

"It's usually the mindset of investors that value creation happens post-deal, but that's probably too late in a lot of cases," said Jacky Lui, PwC's Asia Pacific deals strategy and operations partner.

"The capability lens needs to be considered upfront by investors, especially in private equity, because the market has already factored in the usual programmes such as management reshuffles and cost optimisation. Those are already expected in multiples, which is partially why valuations are higher."

Internal cohesion

Assessments of this kind invariably hinge on intangibles about the individuals involved and their capacity to work together. Team cohesiveness has arguably increased in importance with many GPs opting for longer holding periods. These concerns bleed into the mechanics of longer holds and how decisions are made around instruments such as single-asset and multi-asset continuation funds.

Continuation funds are among the more acute points of contention, with one industry participant estimating less than 10% represent the GP's best assets and full alignment. Most LPs interviewed for this story deferred to guidelines from the Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA) in this area.

Further team-related issues include the makeup of the investment committee, who's on, who's off, and why. Who are the designated key persons and how often have key-person provisions been applied? Motivation and ownership structure can be quantified to some extent in formal compensation, but culture remains the wildcard in this area.

"We have managers that were founded by investors who were very frustrated they didn't get the ownership and economic recognition they felt they deserved and moved on to form their own firms," said an investor at an Asia-based sovereign wealth fund.

"But there are some managers in our portfolio where some of the very best investors do not have any ownership stake in the management company, and that's fine by them. They happen to be good investors and were brought into that regime."

Even where compensation and culture appear harmonious, there is a sense that a more uncertain macro environment – coupled with high levels of dry powder – could exacerbate longstanding challenges around getting comfortable with the risk appetite among the best and brightest.

"They're under pressure to deploy and sometimes take a chance to get deals over the line. If it works, they'll do brilliantly. If it doesn't, they'll just pop off to join another GP," said one industry participant. "You have to make sure they aren't forcing deals past investment committee on the back of personal motivations."

Countering this aspect of private equity requires approaching it as an industry that has become as much about operations as ownership, where sole practitioners can no longer flourish. In this light, GP specialisation has come into focus as a potential indicator of team alignment, motivation, and likely longevity.

Expansion of LP private equity capacity appears to be driving this aspect of GP selection. Institutional investors on this path are becoming ever more aware of their internal PE teams' strengths and weaknesses, and where a specific GP could help them fill a gap. This amplifies the onus on managers to clarify their sectoral sweet spot and differentiated knowledge base.

"We favour sector expertise because we think the market is so competitive these days, you need that focus of skills and insights," said Stephen Whatmore, head of private capital at QIC.

"For many GPs, having a particular sector focus – maybe two – really helps galvanise those teams, their discipline, mindshare, and investment processes. There is less turnover in those groups, and that speaks to team cohesion."

At the same time, LPs' broad desire to pursue more compact manager relationship portfolios suggests the team-level advantages of specialisation will dwindle in relevance.

A prevailing philosophy, at least among the largest players, finds that diversification is best achieved in the underlying company portfolios, not at the GP level. This has translated into the targeting fewer, larger, stabler, and more internally diversified managers. But it's not making selection any easier.

Two distinct trends are driving the phenomenon: the impetus among GPs to go multi-strategy and the blurring of the asset classes that define those strategies. The concern from the LP standpoint is that asset managers in this vein must be judged for a more varied set of returns and results.

Issues of alignment can also arise depending on how the teams are incentivised across a GP's various revenue streams, how big the various business lines are compared to each other, and the extent to which there is overlap between their respective management teams.

There is also the notion that more complex GPs must demonstrate higher competence in terms of teamwork and flexibility. Most investors acknowledge the complementary benefits of a multi-strategy approach but are unsure of managers' ability to juggle talent across different risk and decision-making cultures.

"When you get to the big firms that have every kind of asset class in every jurisdiction at every level, it's inevitable that not all of their teams are going to be of the same quality," said one Australian superannuation fund investor.

"We have a relationship with a big one like that, and we often talk about expanding it, but it doesn't often pay off. It's pretty infrequent that we spread across asset classes with the same partner because we can't get conviction with all the teams."

Flight to quality

Suspicion of multi-asset strategies is not universal among large institutional LPs, but it does appear at odds with almost universal expectations for a flight to quality.

For example, Chris Ailman, CIO of California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS), raises alignment of interest as a significant concern when considering how large GPs have tended to expand beyond a pure private equity approach. But the desire to take bigger bites with fewer managers remains.

"We'll add selectively, and if we're adding, then we're probably not re-upping somebody else," he said, noting that track records have become relatively weaker performance indicators versus cultural factors that are best understood by physically visiting a manager's office.

"It's terribly hard to make a decision to not re-up with a firm or reduce your re-up early. But in reality, you want to sell high, reduce it when they're doing well, and not put a lot when they're doing poorly."

To a large degree, the consolidation of GP relationships is a function of limited bandwidth within LPs. But this has been compounded in the more recent term by pressure to mobilise cash, given its purchasing power is eroding by the day in an inflationary environment.

The overwhelming urge is to access proven managers as quickly as possible. This typically comes with greater capacity to scale co-investment programs and fewer headaches in terms of ensuring professionalism. But it is not without risk.

"If you're going to have a flight to quality, you need to be patient and wait for those high-quality groups to turn up," said Potentum's Byrom.

"Secondaries would be the wrong way to go about getting that exposure at the moment because that's going to give you too much beta, which is really unattractive in this market environment. You need to be able to pace getting that money to work. Don't be in a rush to get it all out the door today."

New Zealand Superannuation (NZ Super) offers an illustrative case study in the difficulties of achieving a compact roster of GPs.

As the sovereign wealth fund has scaled – currently around USD 40bn in assets under management – there has been an instinct to tighten up the alternatives programme and go large. Fund commitments of USD 100m, for example, are not on the cards unless it comes with at least USD 100m in co-investment rights and access to other vehicles down the track.

Still, its number of GP relationships has increased by nine in the past two years alone. This includes three new partnerships under a sustainable transition theme, three in real estate, two in infrastructure, and a tentative toehold in venture capital via a fund-of-funds commitment to StepStone Group.

NZ Super's quality criteria largely revolve around transparency and alignment, but choppier deal markets in the recent term have also highlighted an appreciation for restraint.

"We have one manager that didn't deploy our committed capital because they said they didn't see the opportunity to invest at the price they were seeking," says Del Hart, head of external investments and partnerships at NZ Super.

"We thought, next time they come to market, we will have an increased level of trust with them, and we'll be in a more comfortable position to deploy more capital because they showed discipline."

The firm's highest hurdles, however, are arguably in environmental, social, and governance (ESG), with Hart adding that it is no longer acceptable for GPs to lack a robust process around managing the relevant risks and opportunities in their portfolios. This includes how they assess climate risk.

"We're spending more time understanding not just their capabilities but also their mindset, making sure they have the appetite and belief that this adds value to their portfolios over the long term," she said. "We're moving to thinking about sustainable investment more holistically."

The ESG angle

CalSTRS has made ESG a priority as well, defining it as a basket of business risk compliance considerations that carries the same weight as megatrends the likes of energy transition and ageing populations. The takeaway is that while investors may debate the connotation of E, S, and G, much of which smacks of moral posturing, no GP should be without a plan for the megatrend.

First and foremost, GPs need to find a way to measure their carbon footprint at the portfolio level. This includes attention to at least scope-one and scope-two emissions (direct emissions and emissions from purchased energy) but also plans to think about the complexity of scope three (tracking indirect emissions through the supply chain).

So, do strict ESG requirements whittle down the field to the point where GP selection is becoming easier? "No, GP selection is harder, mostly because of the lack of persistency in returns," Ailman said.

"Just because the GP's been bottom quartile doesn't automatically eliminate them. It's still an uphill climb, but it's somebody you want to think about. And just because a GP is not up to speed right now, these are terribly smart people, and it doesn't mean they can't get there. A GP may go from a climate denier to somebody embracing it."

In Asia, the heaviest ESG compliance overheads come with commitments from Australian superannuation funds, which are seen as in line with European requirements. Interestingly, GPs' shortcomings in this area fall more under the G than the E or the S.

Possibly the most common dealbreaker in this area is proactive event notification arrangements, whereby GPs are obliged to keep LPs abreast of meaningful disruptions to business as usual.

"What we really want is people to say, for example, ‘There's was a cybersecurity event, and we're dealing with it.' But seven times out of 10, GPs are pushing back on that. I can't be constantly asking if everything is okay," said the superannuation investor.

"They'll say, it's not fair to tell us about fraud because the people might be falsely accused. They can't tell us until it is proven and it has gone through a court, and they've been convicted and are in jail. They don't want the responsibility for deciding what's material. There are a lot of what-ifs. But to me, it's a really reasonable ask."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.