Asia renewables: Building out

A surge in renewable energy development is expected in the wake of most Asian jurisdictions making net-zero commitments. Investors are bullish on the macro picture but cautious on the detail

It was a battle that pitched Australia's largest carbon emitter against one of the country's most prominent technology entrepreneurs and, to some extent, a public that had become harshly attuned to the realities of climate change following drought-induced forest fires and heavy flooding.

At issue was AGL's controversial plan to separate its energy retail operations from its traditional coal-fired electricity assets. Both would ostensibly pursue energy transition strategies characterised by low carbon products and renewables, with the former achieving net-zero by 2040 and the latter reaching this landmark in its electricity generation portfolio by 2047.

Grok Ventures, an investment firm established by Atlassian co-founder Mike Cannon-Brookes, was not impressed. In February, it teamed up with Brookfield Asset Management and sought to buy AGL, promising an accelerated timetable for phasing out coal-fired power and a significant investment in large-scale renewable energy and energy storage projects.

A month later, after being rebuffed twice by the AGL board, Grok and Brookfield walked away, with Cannon-Brookes lamenting the company's decision to demerge. AGL and Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP) subsequently announced an AUD 2bn (USD 1.4bn) partnership that would work alongside the coal-fired electricity unit and help it build a renewables portfolio.

By the end of May, though, the demerger was in tatters. AGL abandoned the plan, having recognised it wouldn't receive enough shareholder support, and pledged to consult stakeholders as to the company's future. The climbdown represented a compelling victory for the climate activist lobby, but to some, the line between PR and policy implications is blurred.

"It is helpful when a major energy player is being pushed to decarbonise quicker because it means the Australian renewable energy market will be interesting," said Anthony Muh, Asia chairman of New Zealand-based H.R.L. Morrison, which focuses on infrastructure and property investments.

"[The AGL situation] highlights that the drive to decarbonise is not just a government initiative. But does it really make much difference at the industry level? I'm not sure. Developing renewable energy projects takes time – you need to find the right land with the right resources in a location that has sufficient transmission capacity."

This largely corresponds to sentiment across the region. On one hand, private equity and infrastructure investors are bullish about the long-term prospects of most Asian countries targeting net-zero carbon emissions between 2050 and 2070. They enthuse about rising corporate interest in buying renewables directly as well as government efforts to ramp up green energy tender processes.

On the other, there is uncertainty as to how smoothly policy will crystallise into investment opportunity. Conditions vary across the region. While concerns about transparency, bureaucracy, and insufficient regulatory infrastructure are typically voiced about emerging markets, key questions around transmission, storage, and transportation require answers regardless of geography.

Big numbers

The scale of Asia's climate challenge is lost on no one. "It is so sizeable, anyone who wants to be in this sector must be in Asia. To get to net-zero, we must decarbonise the region," said Daniel Cheng, a managing director with Brookfield's renewable power and transition business in Shanghai.

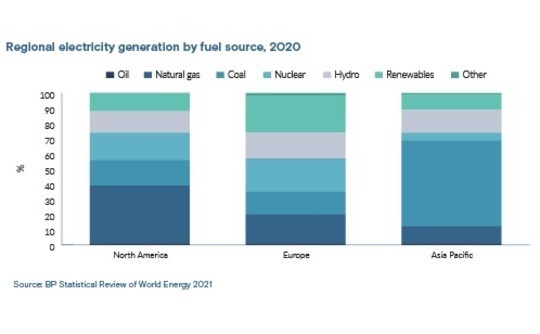

Led by large economies like China and India, which are still urbanising and industrialising, Asia's dependency on coal is plain to see. Coal was behind 57% of electricity generation in 2020, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2021. North America and Europe were on 17% and 15%.

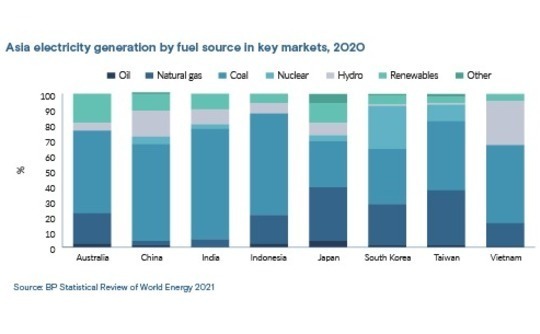

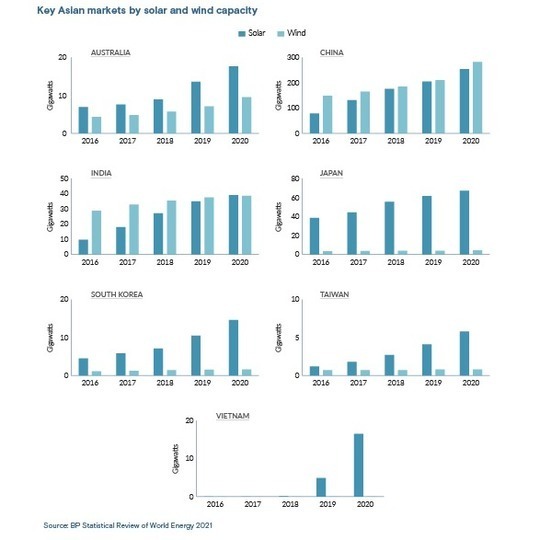

Asia trailed Western peers in terms of the percentage contribution of natural gas and nuclear to electricity generation, but it was on par with North America for solar, wind, and hydro combined. This is largely due to a rapid and large-scale buildout in China, where solar and wind capacity expanded 3.3x and 1.9x between 2016 and 2020.

Some investors avoid China, citing a lack of transparency, but there are other targets. Bruce Crane, head of Asia Pacific Infrastructure at Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan (OTPP), observes that Japan, Korea, and Taiwan enacted renewables regulations several years ago and are now reaping the benefits. Across the three markets, solar capacity grew 1.7x, 3.2x, and 4.8x between 2016 and 2020.

In terms of transaction activity, some of the most visible transition-related deals have facilitated exits for financial sponsors. One key takeaway from AGL and similar situations globally is that the act of hiving off legacy thermal generation assets alone is not enough: it must be accompanied by meaningful plans to retire that capacity and invest in areas like renewables.

Traditional utilities and energy retailers have, therefore, embarked on a shopping spree. Two Asia-based deals from 2022 stand out: Actis sold Sprng Energy, a 2.9 GW portfolio of India-based solar and wind assets to Shell for USD 1.55bn; and Albamen received over USD 1bn from Singapore's Sembcorp for 10 solar and wind projects, comprising 658 megawatts, in China.

In the case of the Albamen portfolio, Sembcorp outbid financial sponsors and SOEs despite pandemic-related travel restrictions limiting due diligence access. Meanwhile, Actis launched the Sprng sale process last November and received 17 non-binding bids, with the Russia-Ukraine conflict only slightly dampening appetite, said Sanjiv Aggarwal, a partner for energy infrastructure at Actis.

It is perhaps telling that the last time the private equity firm sold an India-based renewables portfolio – Ostro Energy in 2018 – the buyer was ReNew Power Ventures, a platform backed by Goldman Sachs and Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) rather than a corporate.

"A lot of large carbon-intensive energy companies now want to transition into clean energy providers, so we see them as buyers of our platforms," Aggarwal added, noting that India-based thermal energy stalwart JSW Energy recently paid USD 1.3bn for a domestic solar and wind portfolio.

"In Sprng, Shell got a set of well-constructed assets and a management team that can help them grow and achieve their own internal targets for capacity. They and others could take early-stage risk, but they tend to back existing management teams where the skillsets already exist."

Platform plays

Actis is ramping up its presence in Asia through several other platforms. In June, the firm launched Bridgin Power to invest in gas-fired power projects across Southeast Asia. It was followed earlier this month by Levanta Renewables, which also has a Southeast Asia remit, but with Vietnam as the anchor market. Meanwhile, a team has been hired out of Macquarie to cover Japan.

Other infrastructure investors are doing much the same. In April, KKR created Aster Renewable Energy to pursue wind, solar, and energy storage projects, initially in Taiwan and Vietnam. It comes two years after the firm launched Virescent Infrastructure to follow a similar strategy in India.

Morrison exited Tilt Renewables, its Australia platform, 18 months ago having concluded that pricing had topped out and the government wouldn't do much. Now, with the country under a new administration, it is looking to reengage. Gurin Energy was set up last year as a pan-Asia operation.

Brookfield, which already has platforms in China and India, is looking to build up its capabilities in Australia, Japan, and Korea, while GIP is expanding Vena Energy, a regional renewables portfolio it acquired from Equis Funds Group in 2018 at a valuation of USD 5bn.

The Equis team launched a new business, using a corporate structure instead of a fund, and raised USD 1.2bn from OTPP and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority for investments in Australia, Korea, and Japan. It is one of three platforms OTPP has backed in Asia, alongside Cubico Sustainable Investments and Corio Generation, with a combined 2 GW in operation or under development.

"As a developer, Equis has expertise in sourcing and executing on early development projects that is hard for us to replicate. That is why we like to fund platforms and management teams with a strategic focus on a particular thesis," said Chris Ireland, a senior managing director for greenfield and renewables at OTPP.

Australia, Taiwan, and India are widely identified as the regional leaders in corporate power purchasing agreements (PPAs). This is driven by renewable energy achieving cost parity with traditional sources and individual jurisdictions introducing the appropriate systems.

"Australia has the infrastructure to sign up corporates directly. Corporate PPAs are the vast majority of PPAs signed in the last 12 months, and the country has a robust electricity exchange and merchant market," said Luv Parikh, a managing director at Partners Group.

"In some other geographies in Asia, corporates are starting to commit to reducing their carbon footprint and would like to sign contracts with renewable generators, but the infrastructure to do so is insufficient."

India is beset by challenges routinely associated with emerging markets. These range from local authorities interpreting federal government policy in different ways to difficulties around construction, although Parikh observes that significant advances have been made in streamlining the permitting process for renewable energy projects and reducing the number of permits required.

Industry participants offer two reasons why India is strong on corporate PPAs. First, it enjoyed a head start thanks to an earlier captive corporate PPA system, whereby companies would take partial ownership of projects and source power from them. Second, developers want to make it work, given some believe tariffs are so low and competition so fierce that selling to utilities is uneconomic.

"The problem isn't a lack of projects, it's finding projects and working with states that can deliver the risk-return profile we are looking for," said Morrison's Muh. "The appropriate rate of return for foreign capital has always been an issue. By the time you take into consideration currency risk, political risk, and regulatory risk it becomes challenging."

Banishing bottlenecks

A key distinction between selling to utilities and selling to corporates is length of PPA – the former sign up for 20 years or more while the latter range from six to 15 years. The shorter the contract, the harder it becomes to secure debt funding on attractive terms, but project finance across most markets in Asia has become more mainstream, and banks can be willing participants.

In certain cases, renewables-friendly government policy has already filtered through to financing terms. Fung of Albamen explained that last year Chinese banks started discounting receivables on customers' balance sheets, enabling developers to realise a portion of energy subsidies as cash. This was followed by regulatory directives encouraging banks to lend to renewable projects.

Albamen refinanced all its projects at a 5.2% interest rate and with a 14-year tenor, only for banks to come back this year with offers of funding at 3.5%. "China Three Gorges [operator of the eponymous dam] is one of the best corporate borrowers in China and it was borrowing at 4.1% last year. We were only 110 basis points higher in terms of credit margin and this year we are lower," Fung said.

China also has an edge over other markets in the region on transmission infrastructure by virtue of its state-controlled apparatus. Industry participants contrast China's ultra-high voltage power lines, which they claim wouldn't be commercially viable anywhere else, with the Australian system, where transmission assets are in the private hands and regulators must incentivise new buildouts.

Australia's transmission bottleneck is notorious, the by-product of a surge in distributed rooftop solar installations and a generally skinny grid that comes under pressure relatively easily. The pan-Asian project developer observes that it takes 3-6 months to bring a completed solar plant online in Australia versus 1-2 days in Japan. Once online, plants can get fined for causing grid congestion.

The imbalance between energy supply and transmission capacity is visible across multiple geographies where renewables portfolios are expanding aggressively, added Morrison's Muh.

"Assets are curtailed because transmission companies cannot take additional energy. Even though projects are generating energy, it isn't being used so it is effectively going to waste," he said. "When people talk about energy transition, they focus on renewable energy generation. They don't think about the other part of the equation, but it is a necessary conversation."

The situation is exacerbated by renewable energy facilities often being located far from load centres where power is consumed, resulting in additional cost and risk. Storage and transportation solutions are required, which would address the intermittency of renewables – peaks and troughs driven by weather events wouldn't be a problem – and ease reliance on the grid as a delivery mechanism.

Green hydrogen is one technology being championed. It involves using power from renewable sources to electrolyse water, splitting it into hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen can be stored for long periods, making it suitable for fuel cells, and it contains more energy than the equivalent amount of fossil fuel. Alternatively, hydrogen can be used to make ammonia, another zero-carbon fuel.

If hydrogen represents mobile storage, then batteries will become the go-to stationary storage option. The technology is already proven and available; the obstacle is cost.

"Currently, if you add a battery solution to your wind or solar project, it will be roughly 30-40% above grid parity. It is difficult to sell that solution," said Parikh of Partners Group.

"Either the grid must provide banking – if the off-taker doesn't consume power when it is generated, then it is pumped into the grid and used for other purposes, and the grid issued a credit to the off-taker – or battery technology improves and costs fall, bringing it to grid parity."

Time will tell

All these avenues will take time to explore, whether it's 18 months as battery production ramps up to the point where supply can satisfy electric vehicles and renewable energy plants, or 10 years as existing infrastructure is repurposed for hydrogen. However, investors recognise that renewables are one part of a very long energy transition journey, with trillions of dollars spent along the way.

This offers context to how geographical incongruities are perceived as well as nascent technologies. There is tendency to divide the region into low-penetration and high-penetration markets, with Australia, Japan, India, and China on one side and Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam on the other. Singapore, which plans to import renewable energy, is somewhere in the middle.

Climate change and energy security – underscored by rising prices in response to the Russia-Ukraine conflict – are forcing more progressive approaches, but markets are neither starting from the same place nor moving at the same speed. Opportunities will come through offshore wind in Japan, widespread adoption of wind-solar hybrids, and Southeast Asia nations scaling up auctions.

"A lot more needs to be done in ASEAN, where government action has not kept pace with market potential. Indonesia, for example, wants to be net-zero by 2060, but its policies on renewables are the same as they were three years ago, if you look at the key aspects," said Aggarwal of Actis.

Yet the sub-region can deliver pleasant surprises. The Philippines, which hasn't made a net-zero pledge, recently ran an auction for 2 GW of solar and wind projects, ending a multi-year hiatus. Thailand is amending legislation ahead of an expected new round of auctions, while Vietnam went from negligible solar capacity in 2018 to 16.5 GW in 2020, not far short of Australia.

This set the scene for Levanta Renewables, but could Aggarwal have envisaged making that investment as recently as two years ago? "Perhaps not," he said. "We weren't convinced. Vietnam was in a frenzy of solar installation and then everything went quiet. We kept asking whether it was part of a longer-term story." Now, though, Actis appears to have its answer.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.