Asia agtech: Work in progress

Global food supply issues and local economic realities are driving more capital into Asia’s agricultural technology space, where business models – from marketplaces to deep-tech – are still being proven

Pure Harvest Smart Farms battled its way to a USD 4.5m seed round in 2017, repeatedly meeting investors who scorned the notion that high-quality produce could be grown in the brutal heat and humidity of the United Arab Emirates (UAE). But Sky Kurtz, the company's founder and CEO, reasoned that if he could prove the technology there, it would work anywhere.

"Convincing people when I had nothing but a PowerPoint, a pile of dirt, and the promise of what we would build was hard," he said. "Once we had the pilot running, operated it for two years and demonstrated the unit economics, we started attracting institutional interest."

Pure Harvest is now a controlled-environment agriculture (CEA) success story, with 22 hectares under operation across four farms in UAE and one in Saudi Arabia that combine top-grade greenhouses and proprietary systems for construction and climate management. The company claims that yields for its water-intensive, short shelf-life perishable fruit and vegetables are among the highest in the world.

Investors are embracing what they previously spurned. Pure Harvest has raised over USD 380m in committed capital, including a USD 180.5m round that closed in June. Korea's IMM Investment contributed USD 50m and is supporting an Asian expansion initially focused on markets that are hot, humid, and have lots of sunlight. Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Korea are on the target list.

Kurtz draws on key macro and geopolitical themes when describing the Asian opportunity: feeding a global population that is growing fastest in arid or humid geographies like South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa; Southeast Asia addressing food security issues by increasing domestic output and easing reliance on China, which supplies half their vegetables and one-third of their fruit.

The other is climate change. "Traditional food production is under attack from irregular weather patterns," he said. "Import-dependent, non-producing nations are not only going to have demand due to demographic factors, but those who supply them will be fighting to meet their own needs."

Investors echo these sentiments. Patrick Vizzone, head of agri-food at Franklin Templeton Global Private Equity, identifies the need to increase food production in a sustainable manner as the main driver of a shift in global agricultural technology investment from downstream to upstream assets.

Rising agtech investment in Asia, however, is underpinned by more than just a global industry upswing. Agriculture accounts for significant portions of economic output and employment in most of the region's emerging markets. Technology applications from marketplaces to hard-tech to biotech are gaining traction, and mainstream investors are comfortable enough to join growth-stage rounds.

"More VCs are in all of these categories," said Mark Kahn, a managing partner at Omnivore, a specialist agtech investor in India. "Agriculture is 25% of India's economy and half of its employment. I see this correction of more mainstream capital coming in as the recognition of something that has always been the case."

Growth-stage awakening

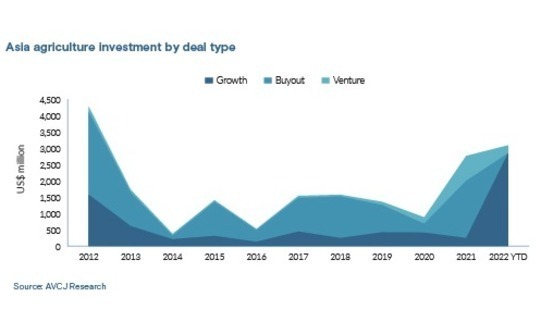

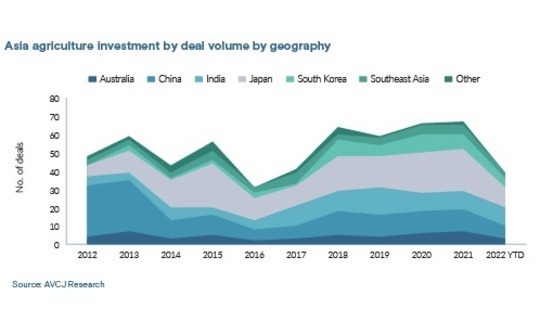

The split between downstream and upstream is reflected in AVCJ Research's investment datasets. Private equity deployment in Asia's overall agriculture sector – not agtech specifically – reached USD 2.7bn last year and the running total for 2022 has already surpassed USD 3bn. The annual average amount for the five years through 2020 was USD 1.1bn.

However, of the 100 or so deals of USD 20m or more since 2012, one quarter – or one-third of total investment during this period – are downstream-centric. More pertinent, perhaps, is the rise in VC, which anecdotal evidence suggests is swinging towards upstream. Deal flow has increased steadily since 2016 and the USD 763m put to work in 2021 was more than the prior eight years combined.

In the past 12 months, DeHaat and Agrostar have closed Series D rounds of USD 115m and USD 70m, respectively, while Arya raised a USD 60m Series C. Participating investors included Schroders Capital, CDC Group, Sofina, Lightrock India, Sequoia Capital India, Temasek Holdings, and Prosus Ventures.

Hemendra Mathur, a venture partner at deep-tech-focused Bharat Innovation Fund and an advisor to numerous investors in agtech, positions these companies as early movers in what became a wave of start-up activity from 2017. Downstream marketplaces that mainly serve retail, restaurants, and individuals, specialist financial technology start-ups, and other advisory players sprang up.

An emphasis on scale-at-any-cost has shaped the development of many marketplaces, and facilitated those follow-on funding rounds, but it is unsustainable, according to Mathur. Investors are now scrutinising unit economics for sightlines of movement from positive gross margins to positive EBITDA – and Mathur said he couldn't name a marketplace that has completed this journey.

"If you are doing staples, your gross margins are 2-4%, so you need large volumes to become profitable. Fruit and vegetables and animal protein, the margins are 10-15%, but additional logistics costs mean profitability has yet to come," he explained. "I'm hopeful, but right now, there is no clear path there. Even some well-funded start-ups are still trying to figure out the product-market fit."

Similarly, Varun Malhotra, a partner at special fintech investor Quona Capital, highlighted how Arya's core competency as a warehouse provider is complemented by financing and commerce functions: farmers can wait for pricing conditions to optimise post-harvest, borrow money against the crops held in storage in the meantime, and have certainty over sale through Arya's relationships with large processors.

"If it were only commerce or just credit, the relationship with the farmer would be shallower – they would just compare you to the highest bidder. Arya is an integrated platform, so they keep coming back. It is woven into the lifecycle and value chain," Malhotra said.

"The founders spent the first couple of years understanding the foundational layer of managed storage and cracking execution. Then they built trust with customers. If you're showing up out of the blue asking to do business with farmers, you will burn a lot of cash acquiring them."

Go narrow, go deep

Moreover, the company has risen to prominence by focusing on one vertical, non-perishable grains. Younger platforms are also targeting economic sustainability through specialisation. Vegrow, which recently closed a USD 25m Series B round, started out focusing on fruit and vegetables before narrowing its scope of coverage to fruit. It is said to be profitable on a contributed margin basis.

The addressable market is still enormous – India's fruit industry is said to be worth USD 60bn – and it presents specific challenges. One is creating supply chains that move perishable produce with different ripening speeds and storage requirements quickly from widely dispersed growing areas to demand centres. Another is meeting the needs of a broad universe of buyers.

"With fruit, you might have 10 different product grades coming from the same tree," said Ashutosh Sharma, head of India investments at Prosus. "The buyer set runs from modern trade through general trade to mom-and-pop stores. For example, the biggest apples go to Wholefoods and the smallest go to street hawkers."

Prosus is one of the relatively recent mainstream converts to Asia agtech. Its debut came last year with the lead investor role in DeHaat's Series C. Since then, the firm has backed three vertical-specific marketplaces: seafood-focused Captain Fresh and Aruna, in India and Southeast Asia, and Vegrow, which it is pushing to expand from apples, pomegranates, and citrus into other fruit categories.

To appeal to Prosus, marketplaces must continuously engage farmers through advisory services in addition to aggregating supply for downstream sale and build trust with farmers by cultivating relationships with other stakeholders in supply chains, such as local store owners who provide inputs. In some cases, marketplaces can become on-demand suppliers to these store owners.

The reality is that most marketplace sourcing is done through intermediaries. Bharat Innovation Fund's Mathur estimates that less than 10% of industry-wide output comes directly from farmers, yet he believes moving further along the supply chain – either upstream to work directly with farmers or downstream to supply produce to end-retailers or consumers – is essential to delivering profitability.

"Either you go deep into the supply chain straight to farmers or you have strong value addition at the farm level through infrastructure, products, and maybe private-label brands. That value addition could be sourcing, rating, and bagging, which now mostly happens at the consumer end," he said.

"A lot of investment has gone into customer acquisition and building digital models, but not enough has gone into infrastructure and product development."

WayCool Foods is arguably the standout Indian example of upstream and downstream expansion. The company, which closed a USD 117m Series D round earlier this year, sources produce from a network of 85,000 farmers, including 3,500 direct smallholder relationships, handles processing in-house, and then distributes to restaurants and retailers under four private-label brands.

Commerce to finance

The same business models are getting traction in Southeast Asia. The Openspace Ventures portfolio includes two agtech marketplaces. Indonesia's TaniHub aggregates output from small farms and sells it to wholesalers and other midstream distributors, while Thailand-based Freshket is more downstream, primarily sourcing from processors for sale to hotels and restaurants.

Nichapat Ark, a director at Openspace, notes that each company is looking to broaden its coverage. TaniHub is in discussions with potential restaurant partners, and Freshket has started sourcing 30% of its produce directly from farmers with processing functions brought in-house.

"The company would still be economically viable even if it hadn't gone upstream, but it would have needed to aggregate more demand from restaurants to have that bargaining power with suppliers and get the right gross profit margin," she said, adding that most marketplaces in Southeast Asia are 12-24 months away from breakeven. "It is also the founder's vision to link farmers with restaurants."

TaniHub and Freshket, which have both raised Series B rounds, identified supply chain pain points based on local circumstances. The same applies to embedded finance, with the former developing its own peer-to-peer funding platform and the latter relying on partner financial institutions.

There is no TaniHub equivalent in Thailand, according to Ark. However, Ricult did aspire to serve as an inputs marketplace when founded in early 2016. It soon became apparent that farmers didn't have the money to buy anything, so the start-up pivoted to focus on this larger problem.

Ricult now sources agricultural data from various sources, including on-the-ground intelligence reports, and uses machine learning-based algorithms to generate analytics and actionable insights. These are sold to around 40 banks, crop processors, and large input suppliers in Thailand, Pakistan, and Vietnam with a view to making it easier for them to do business with smallholder farmers.

"Through our data, we can determine the credit score of a farmer, and that helps him unlock loans from formal banks instead of having to rely on informal loan sharks," said Usman Javaid, founder and CEO of Ricult. He added that the marketplace could be revisited if the financing issue is resolved.

For Indian marketplaces, embedded finance is regarded as a potential key revenue driver. Much like peers in other industries that leverage technology to bring suppliers closer to buyers, they believe customer knowledge can bridge the underwriting gap preventing traditional financial institutions from lending more aggressively to small players.

There are already a few standalone finance businesses that serve the agricultural sector, while the likes of Sammunati expanded from finance into commerce services. The lingering question is whether marketplaces have the bandwidth, talent, and data to become effective lenders. Data is perhaps the trickiest element because it relies on having strong existing customer relationships.

"When someone shops on my platform for less than 2% of their wallet share and shows up once every three months, my underwriting and collections cannot be robust. You need a pool of concentrated power users to provide solutions like credit and payments," said Malhotra of Quona.

Enter agtech 3.0

If marketplaces and the integration of agtech and fintech characterise the first two phases of industry evolution in emerging Asia, then agtech 3.0 will have more of a hard-tech theme. This is already apparent in global capital flows and in the preferences of certain global investors.

Franklin Templeton, for example, examines opportunities through an impact lens and looks to invest at the intersection of compelling market dynamics and government policy. There is a natural affinity for CEA given the macroeconomic and geopolitical context drawn out by Kurtz of Pure Harvest. Alternative proteins and electrification of farm machinery also hit the right notes.

"We look at the potential for impact and the ability for a certain technology or practice to contribute to decarbonisation and the indicative cost saving or cost imposition of that technology. For electrification, the potential and the savings are huge," said Vizzone.

Marketplaces are only of interest if there is a clear impact angle in terms of delivering better returns for producers or financial inclusion. Supply chain disintermediation on its own is not enough.

Recent agtech investment activity in Australia and New Zealand touches on some of these transformative notions. Leaft Foods extracts proteins from plants for use in a range of foods, SwarmFarm developed lightweight autonomous field platform robots that can displace larger machinery, and Loam Bio uses microbes to sequester carbon in farm soils.

All three are at the Series A stage, although Loam Bio's AUD 40m (USD 28m) round is easily the largest. Several farm management platforms for cropping and livestock with integrated software and hardware offerings – such as Halter and Agriwebb – have closed Series B rounds of USD 20m-plus.

"Specialist VCs with agri-food mandates have catalysed participation from sector agnostic VCs like Main Sequence Ventures and climate crossovers such as Clean Energy Finance Corporation spinout Virescent Ventures," said Robert Williams, who leads agri-food VC investments at Artesian, one of those specialists. "Global investors are also coming in like Khosla Ventures and Time Ventures."

Artesian is benefiting from increased corporate interest as well. The firm's first dedicated agtech fund was established in partnership with the Grains Research & Development Corporation, a government agency. Earlier this year, commodities storage giant GrainCorp tapped Artesian to help it establish an AUD 30m sustainable agriculture vehicle.

Deep-tech business models are taking hold in India in the form of drones, robotics, sensors, and satellite imaging. There is a sprinkling of plant bioscience, although industry participants observe that the overall biotech ecosystem needs more support. The recent USD 100m round for Absolute Foods, which is working on phytology and microbiology, is seen as an outlier.

Mathur of Bharat Innovation Fund notes that it will take time for these investments to pay off. "The gestation periods are longer than for supply chain start-ups, where you can get scale relatively early. There might be 2-4 years in development, then validation and go-to-market, so it could be six years before a start-up reaches commercialisation," he said.

Early days

Amid this nascent activity, however, Omnivore has registered India's biggest agtech exit to date. The VC firm invested in Eruvaka, which develops pond health sensors and automated precision shrimp feeders, in 2018 alongside Nutreco, a Dutch animal nutrition business. Nutreco has now bought outright control at a valuation of USD 40m-USD 50m, according to a source close to the situation.

It is the first time a foreign strategic has acquired an Indian agtech company. A key selling point was likely the fact that most of Eruvaka's sales are in Latin America and Southeast Asia, not India.

This is what connects Eruvaka – plus the tail of domestic peers looking to emulate its strategy – to the internationally-minded deep-tech start-ups coming out of Australia and New Zealand. It's also part of the model at Pure Harvest, which wants to bring technology into Asia: the ability to cross borders, expand addressable markets, and potentially become part of the conversation about solving global food problems.

At the same time, it underlines how challenging emerging Asia can be for deep-tech start-ups as they strive for product-market fit at an acceptable price point. Gaorai knows this only too well. As one of few agricultural drone fleet operators in Thailand, the three-year-old company spends much of its time explaining the technology to farmers.

Gaorai's value proposition is that farmers don't need to invest in hardware, rather they can contract out drone spraying when required. The drones are also collecting data that might be monetised as actionable information for farmers. Still, it's a tough sell.

"Farmers work more on impulse, and the reasons they have for choosing one thing over another cannot necessarily be understood and scaled. Some care about price; others don't. You need to be there, speaking to them face-to-face," said Matas Danielevicius, the company's CEO and co-founder. "There is technology, but no one is using it. That's the pain point we are trying to solve."

Solutions take time to bed in. Achieving satisfactory unit economics may involve years of toil. And exits are often works in progress – but Omnivore's Kahn is convinced more will come, whether by IPO or M&A. "A lot of these marketplaces, farmer platforms, and agri-fintech companies were only founded in the last five years," he said.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.