GP profile: Future Capital

Chinese venture capital firm Future Capital bases its investments on strong networks and research as well as a fondness for founders who are not afraid to confound accepted wisdom

In 2015, Xiang Li was best known as the founder of Autohome, China's largest vehicle listings platform, which had gone public in the US two years earlier. Few were convinced the serial entrepreneur could make it in electric vehicles (EVs), reasoning that the expertise required for a technology-heavy manufacturing business was too far removed from running a media company.

Li – who didn't go to college after finding early success with an online computer purchasing guide – persevered with his EV dream, pumping in much of the money he earned through Autohome. Mingming Huang, the founding partner of Future Capital, was bold enough to take a contrarian view.

"By 2014, a new breed of domestic EV manufacturers was beginning to emerge. Mingming and I often discussed changes in the auto industry and the role of Tesla," Li recalled. "One day in early 2015, we met up in Beijing and I explained that I wanted to start an EV business. Mingming replied that he had been waiting a long time for me to do this and offered to be an angel investor."

Huang, who established Future Capital in 2014 after a career as an entrepreneur, had nurtured a longstanding interest in EV. He believed the industry was located at the nexus of two compelling investment trends: rechargeable batteries as replacements for fuel; and the emergence of smart cockpits equipped with driver assistance and entertainment functions.

Two competing EV manufacturers, Nio and Xpeng, emerged the same year and soon began raising capital. It was harder for Li, who named his start-up Li Auto. He wanted to build his own factory and he insisted on developing hybrids instead of pure EVs; both conditions put off large investors, yet the logic was sound when viewed in a local context.

First, in-house production facilities ensure product quality and safety in a Chinese market that sometimes lags in this area. Second, 80% of households don't have fixed parking spaces, so they often lack consistent and convenient access to charging piles.

Launched in early 2020, Li Auto's first and only model – Lixiang One – became the biggest seller among vehicles released by the new domestic EV makers. Over 90,000 units were cleared in 2021, compared to sales of 91,000 and 98,000 for Nio and Xpeng, respectively, across all product lines.

"Great entrepreneurs are often eccentrics. They have deep understanding of local markets, which might be non-consensus. They are super product managers, focused on customer needs without being distracted by issues like investor preferences," said Li.

"They are the soul of their companies. If Li claims to be number two product manager in the automotive field, no one can claim to be number one."

As an investor in Autohome, Huang knew all about Li's iconoclastic tendencies, which saw received wisdom turned on its head in the name of best-in-class customer experience. Consequently, Future Capital didn't hold back when it came to Li Auto. After providing angel funding, it re-upped in all seven rounds prior to the company's USD 1.1bn NASDAQ IPO in 2020.

Venture to growth

The venture capital firm has backed 170 start-ups to date, participating in the angel or Series A round in more than four out of five cases. There have been 28 exits from five US dollar-denominated and two renminbi funds, with Li Auto representing one of three offshore IPOs.

Future Capital raised USD 41m for its first fund and USD 74m for its second, in 2014 and 2015. The firm only disclosed adjusted distributions to paid-in (DPI), defined as distributed proceeds from investments plus marketable securities that could be liquidated. As of year-end 2021, the two vehicles were marked at 3.7x and 2.7x, respectively.

Last year, the firm raised USD 108m for its first growth fund, known as Select Fund Zero. Most of the capital will go into re-ups for existing portfolio companies, extending coverage deep into later-stage rounds. Investments will be restricted to businesses regarded as on course for unicorn status.

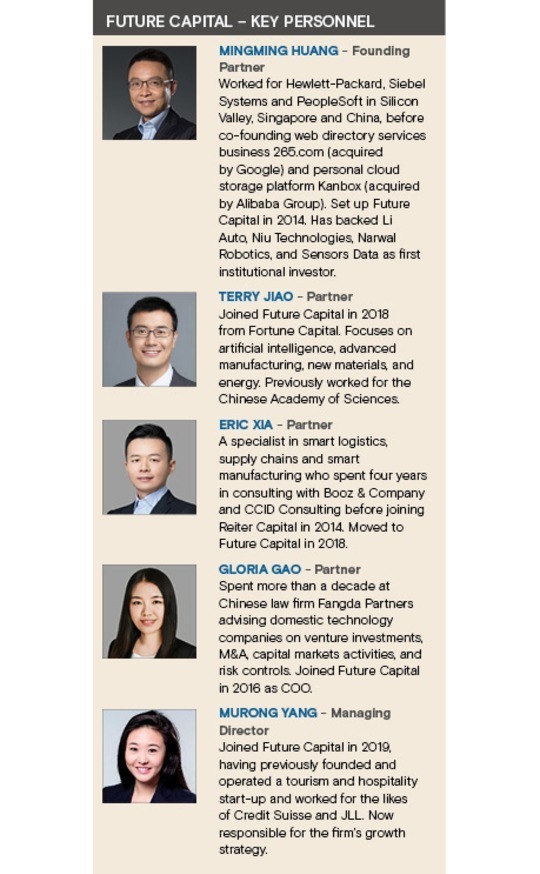

"The idea is to have a strategy that is highly selective and concentrated, backing companies we believe will become absolute leaders in their categories. In this sense, our Select Fund and our early-stage funds are complementary," said Murong Yang, a managing director at the firm who oversees the growth strategy. "We want to support the best tech companies in the long term."

Huang's philosophy of backing entrepreneurs in Li's mould – stand-out product managers whose insight might be mistaken for eccentricity – applies to Future Capital's deal sourcing more broadly.

He met Wenfeng Sang, founder and CEO at data analysis start-up Sensors Data in 2015. Sang had reached out to around 30 top-tier investors and only managed to secure four partner-level meetings. In most cases, progress stalled at vice president level. Sang said to Huang: "If you are like other GPs and only interested in model SaaS [software-as-a-service] companies, we don't have to talk."

From his years spent working at Baidu, Sang recognised that what worked for SaaS in the US wouldn't necessarily work in China: large enterprise users in China were not ready or comfortable to put internal data on the public cloud. SensorsData provided private clouds from the outset.

"When we launched, the Chinese investment community believed in directly replicating the American SaaS model in China. When we proposed doing on-premises [database] deployment, most investors were unwilling to support it," Sang explained. "As it turned out, the strategy helped us quickly gain access to the market at an early stage and beat out the competition."

Future Capital sent a term sheet to Sensors Data on the same day as the meeting. Sang had displayed some of the qualities that Huang cherishes above all others: an understanding of local customers and a willingness to persevere. Last year, Sensors Data closed a USD 200m Series D led by Tiger Global Management and The Carlyle Group. All existing investors re-upped.

"Leading companies in China have their own unique or non-consensus views on local industries and users. And they dare to insist on these points of view, they aren't there to please investors," Huang said. "We attach great importance to this when selecting entrepreneurs. We kind of avoid those who are well-rounded and make you feel very comfortable – those who, whatever you say, agree and follow."

Keeping the faith

A similar story played out with Narwal Robotics. Founder Junbin Zhang was a 20-something postgraduate student when he met Future Capital in 2015. At the time, many start-ups were developing vacuum robots, using US-based iRobot as a model. Noting that most Chinese households have solid wood floors or marble floors rather than carpets, Zhang focused on mopping use cases.

Future Capital came in as an angel investor, but it took Narwal three years to release its first product as Zhang's attention to detail led to repeated delays. For example, he noted that the prototype's two circular mopheads left a tiny gap in the middle; they were replaced with triangular mops. This set back the launch by three months and left Narwal's finances precariously positioned.

Future Capital continued to trust the team and re-upped. When the product finally launched, Narwal quickly carved out a niche in the cleaning robot industry, earning a reputation for delivering quality. The likes of GL Ventures, Sequoia Capital China, and ByteDance have participated in later rounds.

Huang asserts that great entrepreneurs need little guidance from investors: "We never talk much about post-investment empowerment and post-investment value. This may be because I'm a serial entrepreneur myself. If you are so awesome and can help rejuvenate a business, maybe you shouldn't be an investor, you should be running companies yourself."

Strong relationships with entrepreneurs are not solely the preserve of early-stage investors. After Future Capital led a Series B round for cloud gaming service provider Well-link late last year, founder Jianjun Guo approached Huang with a dilemma: Should the company build in-house semiconductor manufacturing capabilities given the policy tailwinds behind the current industry boom?

It was already 10 p.m. but Huang invited Guo to his Beijing office for coffee. Topics of discussion included how battery maker CATL controls a portion of the technology in key components, which gives it more negotiating power when dealing with upstream suppliers.

Guo departed with a newfound resolve: Rather than make semiconductors, Well-link would build specific algorithms into chips, giving it a hold over the intellectual property rights.

More recently, Huang and Guo spent three hours walking in Beijing's Chaoyang Park – Future Capital and Well-link are both based in the city – discussing a new funding round.

"Entrepreneurs and investors can be cooperative, but sometimes they hold opposing views. Future Capital is rare in that we've always felt like they are our own people," Guo said. "We are first-time entrepreneurs, so we have obvious cognitive boundaries. Right now, the markets are undergoing drastic changes. We need accurate information and opinions from those who think from our side."

The other side

Engagement isn't always about expansion and up-rounds. On occasion, Future Capital gets its hands dirty in helping companies that have run into trouble. Electric scooter manufacturer Niu Technologies is a case in point.

The company emerged within the space of a few months. Designer Yilin Hu sent his smart electric scooter business plan to Xiang Li, who passed it on to Huang. Not long after meeting Hu, Huang recommended the project to Yinan Li, formerly a vice president at Huawei Technologies. Yinan Li expressed an interest and soon teamed up with Hu. A founding team was assembled weeks later.

In 2015, 12 months after those initial introductions and two days after a press conference marking the launch of Niu's debut product, Yinan Li was placed under investigation and investors clamoured to withdraw their capital.

Future Capital and Niu's founding team established a five-person working group to address the issue. They met daily to oversee operations. More importantly, Huang persuaded Yan Li, previously a principal with KKR's Capstone operations unit, to join the team. Investors were suitably appeased.

"That generation of Chinese entrepreneurs has such a vision and ambition – to compete head-on-head with the world's best products and companies, relying on technologies and quality rather than so-called price advantage," Huang said. Another Future Capital portfolio company, open-source database provider PingCap, is one of the foremost examples of this phenomenon.

China has yet to produce a software player with the international scope and scale of Oracle, IBM, or Snowflake. Some doubt the country ever can.

Yang has a different perspective. While China's consumer internet industry has peaked, demonstrated by high user penetration and saturated growth, the supporting infrastructure is still delivering dividends. Domestic e-commerce transaction volume is more than that of the US, France, Germany, Japan, and the UK combined, creating a wealth of data points for advanced technology.

Moreover, meeting the demands of e-commerce platforms battling for market share and supporting so much traffic creates a unique environment for those providing the technology infrastructure and back-end software. Developers like PingCap are used to rapid innovation and product iteration.

"We've never separated 2C and 2B, we look at them as a single value chain. For each investment, we consider the upstream and downstream. Innovation on the consumer-facing side is always backed up by innovation in supply chains that comes from related business service providers," said Yang.

The same logic applies to hard technology. China is responsible for half of global EV production, chiefly serving domestic demand. Meeting evolving consumer needs in a fast-growing and highly competitive industry naturally spreads throughout the ecosystem, including companies that make the underlying infrastructure, from chips to sensors.

Future Capital backed automotive chip developer Motor Comm four years ago and the company's valuation has since risen 100-fold. The investment was sourced through Li Auto's network.

Applying insights

Future Capital's investment team maintains lines of dialogue with the company's chief technology officer, head of autonomous driving, and the technical staff responsible for supply chain procurement. Receiving in-depth insights, on a continuous basis, allows the venture capital firm to identify emerging industry trends. It has made more than 20 investments along the EV value chain.

"If you want to exceed market perception and performance, you must invest three to five years ahead of the market," said Huang. "It's not about our insights. It's because we have built and keep on building deep connections with top-tier companies we backed in the past. They are not necessarily the largest players, but they have a cutting-edge understanding of industry development."

This is an important part of Future Capital's strategy, enabling the GP to dig beneath top-down research to identify themes and target companies. However, ultimately it is subordinate to Huang's philosophy of backing entrepreneurs that understand their customers and aren't afraid to fly in the face of conventional wisdom if it results in better-quality products and services.

His relationships and insights are not confined to the desktop. They emanate from constant communication with founders, whether on Zoom, over coffee, or during walks in the park. That helps foster trust - knowing when to be hands-off and trust a team's judgment even when it cuts against self-protective instincts.

With China's technology sector facing significant challenges, Huang draws inspiration from Baillie Gifford. The UK investment manager bought into Tesla in 2013 at around USD 6 per share. It remained resolute through the low periods, from high-level departures to controversies surrounding founder Elon Musk, and made a reported USD 29bn gain.

Similarly, Future Capital hasn't slowed its pace of deployment in China. Valuations have moderated, which is a welcome development. More telling, though, are the implications for founder motivation. For someone to take the plunge with a start-up at a time when market conditions are far from favourable, there must be a compelling customer pain point and an equally compelling solution.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.