Australia take-privates: Going large

A combination of abundant dry powder and friendly financing conditions are encouraging global GPs to pursue ever-larger listed companies in Australia. For now, macro headwinds are no deterrent

The fervour that characterised the last three months of 2021 – when private equity investment in Asia hit a record high of USD 111.9bn – has long since passed. Deal flow in the first quarter of this year amounted to USD 70.9bn, a not insignificant total, yet uncertainties around the Russia-Ukraine conflict, rising interest rates, and volatile equities markets are all too visible.

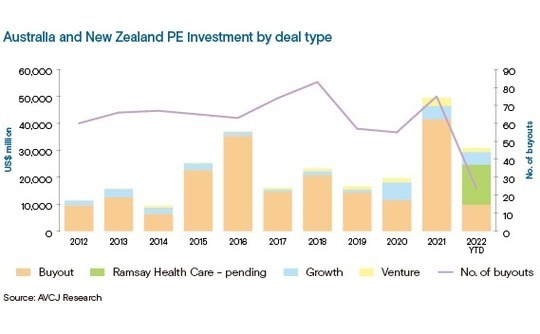

With GPs suddenly gun-shy, only one major market saw an uptick in activity. Investment in Australia reached USD 14.7bn, up 50% on the previous quarter, according to AVCJ Research. The Blackstone Group's agreement to acquire listed casino operator Crown Resorts at a valuation of AUD 8.9bn (USD 6.34bn) was the key driver.

Investment across Asia continues to slow, with approximately USD 15bn committed by the midpoint of the second quarter. Australia is no longer the exception to the rule, but the numbers are based on announced deal flow only. GPs are still aggressively chasing large assets in the public markets.

KKR has offered AUD 20.1bn for hospital operator Ramsay Healthcare while CVC Capital Partners pulled out of a bid for container supplier Brambles – reportedly worth AUD 20bn – at the 11th hour. Should the Crown deal close, it would be the largest private equity buyout in Australia outside of utilities and infrastructure. This glory would be short-lived should KKR reel in Ramsay.

"Many sponsors have a lot of money to deploy. One shouldn't underestimate the weight of that capital and the fact that opportunities to deploy it in sensible efforts is reduced at present. Finding big targets that offer a solid base for investment and put a lot of capital to work is attractive," said Mark McNamara, a partner at King & Wood Mallesons.

There are various subplots. Australia's large-cap buyout space is highly competitive with not only global private equity firms chasing opportunities, but also core-plus infrastructure managers with lower costs of capital. Lining up a mega-deal with complex financing and ample co-investment is a potential antidote: the few GPs capable of mounting a challenge are constantly playing catch-up.

Most Australian companies of suitable size are listed, so the public markets are a logical place to look. It played out the same way in the mid-2000s when annual buyout activity topped USD 10bn for the first time. While some are wary of drawing parallels with the boom-and-bust of the global financial crisis, noting differences in sector targeting and financing structures, others don't hold back.

"Australia's GDP is smaller than Korea's and you don't get USD 15bn leveraged buyouts in Korea. I'm reminded of 2008 and it's not only Australia. Buyouts are reaching USD 30bn in the US and USD 17bn in Europe; these are levels we haven't seen in 15 years," said one pan-regional fund manager.

"Over 50% of Brambles' business is in the US and US is heading for a recession. Walmart and Target have announced slowdowns – it's going to be brutal for retailers [who are Brambles customers]. These deals will only work out if you take a longer-term view and invest through long-dated funds. Even then, the IRR might only be 10%, which is fine for infrastructure, but not for private equity."

Safety in sectors?

Global GPs run multiple strategies and it is unclear how these mega deals will be divided up between different pools of capital. KKR has used its core investments – or longer hold, lower risk profile – strategy in Australia before. Several Blackstone real estate funds are mentioned in Crown's filings.

However, infrastructure and infrastructure-like returns are a prominent theme among the 16 take-privates completed and 11 announced since the start of 2021. Financial sponsors feature in 10 of them, including waste management business Bingo Industries, Tilt Renewables, broadband providers Vocus and Uniti, Sydney Airport, Spark Infrastructure, and power grid operator AusNet Services. Real estate is also represented.

There is more industry variety in the deals pending than in those completed, but sponsors are focusing on what they see as defensible. Crown is an exception – a business mired in regulatory troubles that could be ripe for a turnaround. Healthcare (Ramsay) and logistics (Brambles) are seen as more representative of the general mood.

In some cases, there is a reassuring real assets angle buried in a PE deal. Ramsay owns 54 of the 72 hospitals and surgeries it runs, creating a sale and leaseback opportunity that Macquarie estimated could be worth as much as AUD 8.7bn.

While any public company could theoretically be picked off, these situations can be fraught with difficulty. Company boards are bound to push for the best outcome for shareholders, which often results in incremental price increases as deals progress from bidding through due diligence and shareholder vote. Blackstone is paying a 48% premium for Crown over what it originally offered.

Deals can become acrimonious. In the pending group is fertility care player Virtus Health, which has agreed to an AUD 706m acquisition by CapVest Partners. However, BGH Capital, which made the initial approach, is refusing to concede. Australia's takeover panel has received two complaints, one claiming Virtus' board was unable to entertain rival binds, and one saying it wasn't willing to engage.

"Public to privates are harder to do in Australia. In other markets, they tend to be initiated by management, which convinces the board. In Australia, the primary form of communication is with the board," said Anthony Kerwick, a managing director at Adamantem Capital.

"Non-executive directors are well-represented, and they have a fiduciary duty to act in the interests of shareholders. They will explore whether another buyer can pay a fuller price."

Simon Moore, a senior partner at Colinton Capital Partners, who was previously Australia country head at The Carlyle Group, added that board members often hold few shares, so their personal economic interests are not necessarily aligned with maximising shareholder value even if that is the requirement. Moreover, some recognise they will lose their roles if they support a privatisation.

Boards are also subject to pressures from multiple constituencies – including institutional investors that might oppose a sale – so a seemingly attractive private equity offer doesn't elicit the expected response. There might be a difference of opinion as to whether and how soon the approach is disclosed, sometimes resulting in leaks by aggrieved parties.

"It's never a straightforward process," said Moore. "The response to the initial approach sets the course of the engagement. Some of it is down to the personality of the private equity firm, whether they want to play the long game or press the company into a process. The private equity firm must also assess the personalities on the board and how they are likely to respond to certain behaviour."

New habits

The recent crop of take-privates is notable not only in its overall number, but also in how many proposals have been made and then withdrawn. Brambles is one of seven that have stumbled since the beginning of 2021. Three of the six led by financial sponsors involved software providers: BGH and Hansen Technologies, EQT and Iress, and TPG Capital and Smartgroup.

Failure to agree pricing following a post-offer spike and businesses not appearing so compelling on closer inspection may have contributed to these abandonments. Tim Sims, a managing director at Pacific Equity Partners (PEP), which has completed eight public-to-private deals, offers another theory: GPs are moving quickly on assets and reasoning that they can work out the details later.

"Historically, PE Firms in this market, have been very circumspect before announcing a bid for a public company," he said. "One possible conclusion is that some private equity firms, particularly with backgrounds in other markets have deviated from this historic playbook."

The playbook is also changing in terms of the willingness of GPs to build up positions in public companies before they make a formal approach. Again, understanding the personalities involved and how they might respond is key. Will target companies look for alternative solutions rather than do business with what they perceive as an overly aggressive party or appreciate the seriousness of the offer?

"That stake building tactic is more common than it used to be," said McNamara of King & Wood Mallesons. "People have decided it is important from a board interaction perspective because it gives you credibility. It also protects your downside from interloper risk. You don't have the protection of a normal private process. Someone could buy a stake and stuff any chance of a deal."

BGH built up a 19.99% stake in Virtus – reaching 20% triggers a mandatory tender offer – prior to submitting a take-private bid last December. CapVest was willing to pay more but BGH has enough shares to block a full acquisition through a scheme of arrangement. In response, CapVest made a parallel off-market takeover bid with a lower acceptance threshold.

BGH may play the waiting game, reckoning that CapVest would rather withdraw and focus on other opportunities than run Virtus as a listed enterprise with a recalcitrant 20% shareholder on the register. Alternatively, the private equity firm could sell at a premium and allow CapVest to proceed, much like what happened when it lost out to Brookfield on Healthscope.

Virtus has received seven competing proposals from BGH and CapVest over about three months. Some pursuits have lasted even longer, such as PEP's acquisition of cleaning and catering contractor Spotless despite board resistance in 2012. In another instance, PEP held power distributor Energy Developments as a public company for five years after 25% of shareholders rejected a privatisation.

Overt hostility must be underpinned by a conviction that the target is truly mismanaged and undervalued. "If we cannot conduct due diligence and get access to enough information, we don't want to buy an asset, friendly or unfriendly," said the pan-regional buyout manager. "And if the situation is unfriendly, you don't really know what you are bidding on."

Middle moderation

The dynamics are often less fraught in the middle market. Adamantem's Kerwick notes that Australia hasn't seen a decline in the number of listed companies like the US and UK, but the same underlying drivers are present. A shift from active portfolio management to passive index tracking means fewer institutional investors want to hold smaller companies, while reduced research coverage at investment banks makes it harder for those same companies to raise capital.

"It is especially difficult if a company wants to change direction and needs investment, which involves taking on more debt or turning off the dividend tap. These would be viewed negatively in the public markets," he said. "At the same time, the relative balance of capital between public and private markets has changed enormously. Private markets can continue to fund companies."

Two of the six investments in Adamantem's first fund were privatisations. One of them, Zenitas, was caught in the classic public markets bind. Near-term headwinds were expected in homecare and disability care but the long-term prognosis was strong. The company recognised it would struggle to raise capital to support growth and so Adamantem's take-private proposition was readily received.

The mindset Moore described of how global sponsors think about take-privates is entirely different: "There will be half a dozen targets you've done work on, have management solutions ready to go, and you're waiting for them to come into strike zone. If the markets start moving, you either modify the proposal to reflect the conditions or you pay what you thought you might have to pay."

Assuming bids for the likes of Ramsay and Brambles were months in the making – likely, given the co-investment requirement – market conditions have moved substantially since deliberations began. Despite macro and geopolitical headwinds, the sponsors resolved to continue, helped by relatively little alteration in the quantum of financing and in the terms on which it is available.

"The Australian market is well-positioned in terms of sources of liquidity and the depth of those sources. There is too much competition for there to be a significant tightening of terms," said David Couper, a partner at law firm Allens.

"In the last 18 months, we have seen a lot of new entrants with very deep pockets. Ares SSG is now established here, Goldman Sachs Asset Management is ramping up on private credit, and there are many mid-market credit funds that can pool together and offer tickets of AUD 300m to AUD 500m."

When it comes to the larger transactions, no one financing market – commercial banks, financings underwritten and syndicated by investment banks, and the private debt providers – has done them all. Ramsay is a global company, generating more revenue internationally than within Australia, so KKR would likely tap the US term loan B (TLB) and euro high yield markets as well as local sources.

"Given the quantum of debt required, you have the flexibility to go into different markets globally," said Graf of Ares SSG. "Do you want a different type of instrument that sits behind first lien senior secured? Does that stay at the operating company level, or do you do some holdco mezzanine? Could you break the business into parts and finance them independently?"

Cyclical and structural

Sponsors are thinking more carefully about their equity theses and the consistency of cash flows, but when it comes to financing terms, there is more talk than action. For the first time in years, Graf has seen all-in interest rate exposure return to the agenda. Some managers are asking about replacing floating rates with fixed rates – asking, not doing.

Russell Sinclair, head of Australia debt and capital advisory at PwC, believes the interest rate covenants dropped from many US TLB deals last year – leaving just the gearing ratio covenant – could be primed for a return. "But it's for smaller borrowers only, not larger deals," he stressed. "And it's a discussion that's only just beginning."

There has been a shift in pricing, with Sinclair noting that high-yield rates are rising rapidly in the US. The consensus view is that it translates into a 100-200 basis point increase for deals out of Australia – not enough to stop a large transaction. After all, recent volatility means many companies are trading below pre-COVID-19 levels when approached by private equity and the investment thesis is in part predicated on recovery.

"The noise is there, but it's not enough to deter people," Couper of Allens added. "If it intensifies, and negative impacts are realised in the market, activity will drop. We just don't see that happening in the next six months."

Meanwhile, in the background, there lingers a long-term structural factor. The negative stigma in boardrooms about taking the privatisation route has largely dissipated, replaced by a recognition that public markets may not be the ideal venue for companies keen to pursue growth or transformation. Sims of PEP argues that private equity is now the optimal long-term backer.

"There is often an enormous amount of short-term performance pressure on public companies, which can compromise long-term strategic options. Share prices can be fragile and volatile, and public shareholders tend not to stay very long. That's a difficult platform on which to build if your industry is under pressure," he said.

"Those could be times when a different form of capital is required to maximise value."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.