China outbound: Organic options

Tough domestic competition is encouraging Chinese tech start-ups to expand overseas – often organically, earlier in their lifecycles than before, and despite regulatory concerns

Dreame spent three years perfecting its first product, but it proved time well spent. The Chinese company, established out of Tsinghua University, released a vacuum cleaner to great acclaim in 2018. It soon expanded into sweeping and mopping robots and hair dryers, all based on a motor capable of 150,000 revolutions per minute (RPM). Dyson was the previous global leader on 125,000 RPM.

"Our vision is to become a world-class technology company. Dyson remains the leader in home cleaning, but we believe we are the only rival of equal strength," said Roc Woo, a founding partner of Dreame. "We originated in China because it has solid industrial foundation and top engineers. We invested heavily in R&D from day one, choosing the path of technology accumulation."

The company recorded sales of CNY 2bn (USD 297m) in 2020, up from CNY 500m in 2019, while growth was up more than 100% year-on-year in the first six months of 2021. Notably, 70% of revenue comes from overseas markets. Dreame's products have topped the selling charts on AliExpress and Amazon in multiple European countries in the EUR 200 (USD 210) and above bracket.

"When you go global from day one, you embrace higher product standards. Consumers in Europe and the US are more demanding in areas like home appliances, so you need strong R&D capabilities to meet their needs," said Ming Lei, who leads consumer internet at China Renaissance's Huaxing Growth Capital. The firm co-led a CNY 3.6bn Series C round for Dreame last year.

At the same time, Dreame and its Chinese peers are venturing overseas in response to intensifying competition at home – reflected in rising marketing costs and rapid product iteration cycles.

In the home cleaning electronic appliances space, for example, 90% of sales in China are through e-commerce channels, which places a premium on online traffic to drive market share. According to Woo, there is a natural Matthew effect, whereby the top three players eat up 90% of the market and the cost of joining that exclusive set is huge.

The product iteration phenomenon is underpinned by the close geographic connection between industrial supply chains and end consumers. Feedback comes swiftly and is channelled into demand for new versions. Manufacturers are pushed into an endless cycle of upgrades.

"If you do not count the current period of market turbulence, I believe the trend [of Chinese companies going global] is increasing," said Wanlin Liu, a managing director at The Carlyle Group. "We are seeing more companies going global without having established successful and sizeable domestic businesses, typically in areas where domestic competition is intense. Competition is less cut-throat in overseas markets."

Three waves

A China Europe International Business School (CEIBS) survey published in late 2021 found that two-thirds of respondents are engaged in overseas business activities and half participated in investment outside of China or in overseas capital markets. While only 14% generated over half their revenue internationally, there is a strong desire to increase this among tech sector representatives.

Geopolitical issues are top of mind – tariffs, market access, intellectual property, and investment rules were among the most frequently cited in the CEIBS survey – but not necessarily a deterrent. A separate study by Boston Consulting Group found that 85% of respondents from digital companies not considered market leaders cited intense domestic competition as the key reason for going overseas.

In this sense, the current wave of outbound expansion involving technology companies differs from the two that preceded it. The exact starting point of the first is unclear. Huawei Technologies began selling communication equipment to Russia in the late 1990s and gained parity with Apple and Samsung in the global smart phone manufacturer rankings in 2020.

Those three brands achieved prominence in South and Southeast Asia after establishing domestic dominance. Their major selling point is "value for money," said Ben Harburg, a managing partner at Chinese VC firm MSA Capital. They offer something much like Apple but at a lower price point.

The second wave, from the mid-2010s, was led by consumer internet giants Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings. They expanded their footprints in e-commerce, gaming, social media, and financial technology through a combination of organic and inorganic strategies.

Alibaba turned AliExpress into a global name and made direct acquisitions in the likes of Southeast Asia, Pakistan, and Turkey. Tencent has combined landmark buys like Finland-based mobile game developer Supercell with a portfolio of minority investments. It was an early backer of Sea, operator of the Shopee e-commerce platform, which overtook Alibaba-owned Lazada in Southeast Asia.

"The first two waves involved the geographic growth of large Chinese companies that had traditionally focused on the domestic market," Harburg added. "The third – the so-called Chuhai (which means ‘go overseas' in Chinese) is different. Those are China-built companies whose primary market is not China."

Shein-ing example

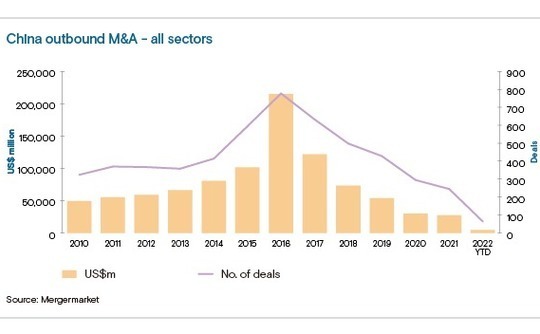

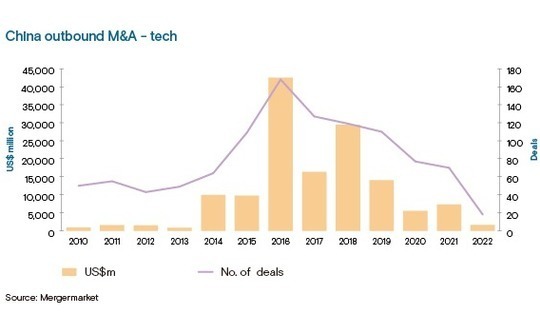

Expansion tends to be organic rather than through M&A. Chinese outbound M&A peaked in 2016 and has declined every year since then, chiefly because of restrictions imposed by Beijing on cross-border investment and increasingly challenging approval regimes in target countries.

The technology sector broadly follows this trend. M&A topped USD 42bn in 2016, the year Tencent acquired Supercell, according to Mergermarket data. In 2021, it reached USD 7.3bn, a modest year-on-year increase but still a fraction of the previous highs. The downward trend was broken in 2018 when there were a couple of significant semiconductor deals, but those are unlikely to be repeated.

Fashion e-commerce platform Shein typifies the third wave. Though largely unknown domestically, the company leveraged social media to build a strong following among US teens, gaining a 28% share of the US fast fashion market. Shein's most recent funding round reportedly closed earlier this year at a valuation of USD 100bn, more than the combined market capitalisation of H&M and Zara.

"Shein is a very successful supply chain company. It has opened up a direct link between Chinese factories and overseas consumers, taking the ‘small order, quick iteration' philosophy to the extreme," explained China Renaissance's Lei.

The common factor – from clothing to consumer electronics and everything in between – is China's manufacturing strength, in terms of quality and cost. Daisy Cai, a general partner and head of China at B Capital Group, credits manufacturing clusters found in the Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta with enabling this outbound push.

"In the past two decades, China has established mature industrial supply chains with operating efficiency that far exceeds other countries," she said. "This has nurtured a number of leading companies with international competitiveness."

Hard and soft

It is an export-driven phenomenon that has shifted from products into services, from hardware into software, and back again. The consumer internet companies replicated their business models overseas, deploying Chinese teams to leverage internet traffic just as they had done domestically. Community group buying and social networking and media sharing are recent examples.

Online payment also qualifies. Low credit card penetration and high smart phone penetration combined to turn China into the world's largest mobile payment market and make Alibaba affiliate Ant Group's Alipay is the number one platform. Ant is the largest investor in Paytm, India's market leader. The business model is now making headway in Africa with VC-backed Chinese start-up Opay.

ByteDance-owned short video platform TikTok is often cited as the most recent successful Chinese mobile internet export, although its high profile has led to regulatory issues, and bans, in some markets. The company gained a technology edge with the acquisition of Musical.ly in 2017 and has since grown TikTok into more than just an overseas equivalent of Douyin, its Chinese product.

"ByteDance has explored and formed a whole set of playbooks suitable for overseas markets and it has threatened Facebook's leading position in the social software space," added Cai. "From the export of Chinese business models to original Chinese innovations for overseas markets, we see that Chinese companies are constantly upgrading as they go global."

In recent years, investors have pivoted from mobile internet to business services and deep-tech domestically. Michael Yao, a partner at ZWC Partners, which makes early-stage cross-border investments, identifies a similar trend in outbound expansion, with the mobile internet opportunity largely exhausted. Supply chain capabilities and integrated hardware and software are now in focus.

Robotics is a case in point. In addition to Dreame, the likes of Roborock and Ecovacs have quickly gone global and now compete head-to-head with iRobot in the US domestic robot market.

In the industrial space, Geek+ has claimed a 10% share of the global autonomous mobile robot market by supplying warehouse operators. VisionNav is looking to do the same for driverless forklifts and tractors, with more than 50% of its revenue expected to come from overseas. The US is a key target market. 5Y Capital and Meituan recently led a USD 80m Series C extension for the company.

"Robots are a combination of algorithms and manufacturing. China has a great advantage in manufacturing, while its algorithm software is also strong. As overseas manufacturers lack the hardware ecology of places like Shenzhen, their product iteration is slow. This translates into a huge competitive edge for Chinese players," said Peter Chen, a managing director at 5Y.

However, he notes that timing for overseas expansion is critical. It takes up to five years for a new robotic product to achieve maturity and become internationally competitive. Before then, maintenance and repair costs in overseas markets are prohibitive.

Tried and tested

China is also proving its international credentials in high-end manufacturing across the electric vehicle (EV) supply chain – an area where domestic players are arguably superior to foreign peers.

CATL has become a global leader in lithium-ion batteries with a 30% market share. Overseas revenue rose 252% year-on-year to CNY 27.8bn in 2021, making up 21% of overall sales. Tesla is its largest customer, accounting for 10% of revenue. The overseas gross profit margin is 30% compared to 22% overall. Svolt, another domestic battery maker, is also pushing into international markets.

Some private equity investors observe that the window of opportunity for batteries is closing – the incumbents are too strong. However, they still see potential in areas like autonomous driving technology. China-based LiDAR developer Hesai generates 60% of its revenue from overseas with Bosch Group and Aurora Innovation disclosed as customers.

"Equipment for high-end manufacturing is actually very difficult to produce. Chinese companies like Hesai not only do R&D on products, but also on manufacturing equipment. China's manufacturing capabilities give these companies an edge on US peers, and they can be much faster in product iteration," said James Mi, a founding partner of Lightspeed China Partners and an investor in Hesai.

China is less advanced in software than manufacturing, but some start-ups are still vying to become global players. Founded in 2015, open-source cloud database service provider PingCAP opened a US office in 2016 and now has 50 local staff. Half its revenue comes from overseas.

"China is already at the same level as top global players in the field of databases. About half of the most popular open-source database projects are developed in China. There are no national borders in this field, and targeting global markets creates a multiplication effect," said Ed Huang, co-founder and CTO of PingCAP.

The country is competitive in infrastructure software because of its large-scale data volumes, huge workloads, and incessant demands from local internet companies that are growing – and accumulating data – almost faster than they can back it up. Chinese database developers have, by necessity, earned a reputation for quality and stability, which has begun to resonate globally.

The same applies to some application software, typically in the software-as-a-service (SaaS) space. China is in the early stage of digitalisation and local customers aren't always clear about their needs. Consequently, software companies must be very hands-on and end-to-end solutions are preferred.

"In overseas markets, you can live well on a strong single product, but in the Chinese market, you have to do this layout of full service. Once you achieve this layout, you can expand geographically, and in fact, you will have certain advantages," Lanchun Duan, a managing partner at Cathay Capital, told AVCJ in a recent interview.

Cathay is an investor in Laiye, a China-based artificial intelligence and robotic process automation (RPA) specialist that claims to be winning deals from the likes of UiPath and Microsoft. Europe accounts for 20% of revenue. CEO Guanchun Wang expects it to be 50% by 2025, noting that the company's product matrix "has been tried and tested in the tough China market."

Opaque or transparent?

Regardless of industry, regulation looms large over corporate China's outbound ambitions. It is most visible in deal vetoes and sanctions – the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS) and other agencies closely scrutinise M&A and various Chinese companies have been cut out of global supply chains – but can be manifested in all kinds of ways, from licensing to recruitment.

There are two general responses. First, a company might seek to position itself as non-Chinese, which one executive from a global private equity firm describes as an increasingly common play. Second, it tries to be as compliant and transparent as possible.

Having established a global compliance division in 2019, PingCAP has adhered to requests to comply with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), industry-standard operating procedures, and International Organization for Standardisation (ISO) protocols. Dreame has teams in each region addressing intellectual property, legal, finance, and tax issues. Nevertheless, challenges remain in areas like procurement.

"In Europe, the US or Japan, when a large local telecom company or a bank considers a software service from China, they worry that in the current environment services might be interrupted and cannot be offered on a continuous basis. This brings extra challenges for Chinese enterprises looking to sell overseas," a SaaS-focused investor told AVCJ.

Moreover, the preference for organic expansion isn't solely rooted in regulatory uncertainty. Carlyle's Liu notes that M&A comes with a litany of integration issues – from language to culture to time zones – whether Chinese companies are buying assets overseas or foreign businesses are entering China.

Harburg of MSA discourages M&A unless it is required to negotiate an otherwise insurmountable obstacle like obtaining a license. PingCAP's Huang also advocates organic expansion as a means of slowly and steadily accumulating local knowledge.

"I prefer to build up a local team in a hands-on way rather than acquire an existing business," he said. "In building up the team, I get to understand the target market. The best globalisation is about localization. You can't be that localised through a quick acquisition."

At the same time, whatever complications Chinese companies face overseas might pale in comparison to the environment domestically. The technology sector has undergone tremendous upheaval in the past 18 months as regulators sought to clip the wings of local internet giants and reign in perceived abuses across the ecosystem.

As one investor points out, many Chinese companies have responded by looking to establish international headquarters in Singapore or introduce offshore structures as a hedge against further domestic disruption.

Indeed, some rue not going global earlier. Shiwei Xu, founder of Chinese cloud service provider Qiniu, observed in a recent article that many tech players have waited too long.

A popular development arc for start-ups now being established might be to deploy resources globally from inception rather than turn a China-centric narrative into an international narrative. A truly global vision enables the creation of truly competitive products and a reassuring level of diversification in a world increasingly characterised by nationalist economic policy.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.