China VC: Funding puzzles

Late-stage investors are appearing in earlier funding rounds in China, offering premium valuations but potentially leaving start-ups in situations where they have too much too soon

Sequoia Capital China has achieved a scale unmatched by any other US dollar-denominated VC firm in the country. Its most recent fundraising effort in 2020 saw USD 180m accumulated for seed investments, USD 700m for venture, and USD 2.8bn for growth deals. Sequoia can back a start-up and stay involved throughout the private market journey.

No one exerts such power and influence without attracting critics, regardless of whether the barbs are warranted. A current bugbear among smaller investors is Sequoia's perceived habit of paying up to secure a foothold in early rounds, so that it is well-positioned to write larger cheques in later rounds as companies appreciate in size and value.

"We have all gathered around Sequoia at an investment summit and criticized their super-high valuations," a renminbi fund manager told AVCJ. "They are destroying the ecosystem."

This is not solely a Sequoia problem, a point stressed by multiple sources. Numerous deep-pocketed tech investors are looking to capture more alpha by deploying their capital earlier, which means valuation pressure at the growth stages filters through the entire ecosystem.

Hillhouse Capital Group, Tiger Global Management, and SoftBank's Vision Fund series are high-profile examples. But technology is a key vertical for generalists as well, whether they invest across the spectrum like Warburg Pincus, have dedicated growth vehicles like Boyu Capital, or place expansion rounds alongside more traditional investments in flagship funds.

Last month, a Chinese publication ran a story titled "Beijing-style investors, please get out of the industrial Internet circle." It circulated widely in the private equity and venture capital community, either denounced as sensationalist or endorsed as a reflection of the times.

Industry participants are happy to offer definitions of "Beijing-style investors," highlighting a willingness to pay a heavy premium to access opportunities and a tendency to apply consumer-internet expansion logic to industrial internet or business services companies. They are also willing to point fingers – just not publicly.

"These investors have done well in the past, so they raise larger funds," said one long-standing China GP. "Their tentacles reach every corner of the market, from angel rounds to buyouts to secondary investments. They also participate as LPs in funds or fund-of-funds, which gives them access to second-tier managers. This power should be constrained."

Shifting momentum

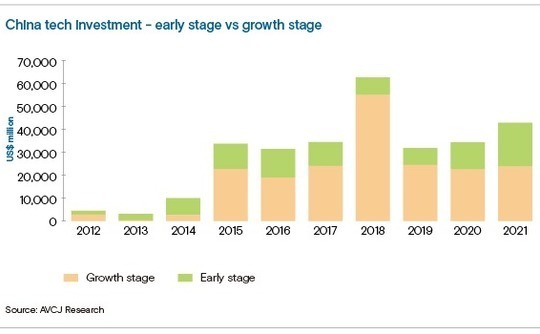

The go-earlier phenomenon has arguably become more accentuated in the past 12 months. The flood of capital into growth rounds for Chinese technology companies began in 2015 and continued uninterrupted until last year. Even though the headline number for 2021 – USD 23.8bn – is consistent with recent years, activity dropped off in the second half when China spooked the market with a string of regulatory actions.

Approximately USD 1trn was wiped off the value of US-listed Chinese technology companies between February and December. This created a mismatch between public and private market valuations that has yet to be reconciled.

"The valuation multiple of the primary market exceeds that of the secondary market in certain industries. As a result, some investment firms are looking to transfer part of their mid to late-stage investment allocation to early or growth-stage projects," said Kyle Xu, a managing director in China Renaissance's investment banking division.

"They are taking a wait-and-see approach on mid to late-stage investments. There is now less competition in the space with valuations falling, but at the same time, Series A and B rounds are very active. A lot of late-stage investors are participating in that space. We are one of them," said Daisy Cai, a general partner and head of China at B Capital Group.

These sentiments are reinforced by numbers. Early-stage investment in Chinese technology start-ups also spiked in 2015, reaching USD 11.1bn. It then plateaued, averaging USD 10bn over the next five years, before jumping to USD 19.3bn in 2021, according to AVCJ Research.

In some cases, shifts in strategy by late-stage players are highly visible or publicly acknowledged. SoftBank Vision Fund 2, for example, is going smaller and earlier than its predecessor. Cheque sizes in China are said to be as low as USD 30m.

Primavera Capital Group, which is reportedly targeting up to USD 5bn for its latest China fund, is part of the cohort of GPs launching dedicated early-stage investment platforms. Primavera Venture Partners (PVP) was established in 2020 to focuses on artificial intelligence, next-generation technologies, healthcare, climate change, and advanced manufacturing.

"We are paying special attention to cutting-edge technologies and even moving towards seed rounds, incubating and supporting stand-out teams," said Johnny Zou, cohead of PVP. "We are seeing explosive opportunities, and a lot of high-quality start-ups, in our target sectors. I've no doubt there will be more early-stage initiatives from mega-funds."

The notion that this transition leads to inflated valuations is endorsed by Thomas Chou, co-head of the Asia private equity practice at Morrison & Foerster. He has tracked a very significant increase in valuations between Series A and B rounds. At the same time, traditional late-stage investors going earlier isn't necessarily a new trend – more a familiar characteristic of boom periods.

"In my experience, VCs in China have historically faced a very competitive deal sourcing landscape. In the years leading up to the global financial crisis in 2008, it was the hedge funds that were in focus for offering high valuations with minimal due diligence, and for years thereafter it was the renminbi fund managers identified as driving up valuations," said Chou.

No guarantees

Early-stage deals, when pursued by well-resourced technology sector investors, sometimes form part of so-called platform strategies. They conduct methodical top-down research, identify key themes or segments, and then pursue the most significant players. Like Sequoia, it is all about getting in early and deploying more capital as companies scale.

Tiger Global is regarded as a prime exponent of the platform strategy. Crunchbase noted in late December 2021 that Tiger Global had made 335 investments globally year-to-date, a total exceeded only by accelerators Y Combinator and Techstars. One financial advisor observed to AVCJ that the firm is light on company-specific due diligence and heavy on valuations.

This approach is no guarantee of success. The start-up with the most capital doesn't always prevail in a hypercompetitive environment, and then when platform investors back multiple players in a single segment there is a tacit acceptance that some will fail.

In 2018, Tiger Global led a CNY 300m (USD 44m) round for Udesk, a China-based customer service software provider, making it by far the best-funded and highest-valued company in the segment. Since then, fundraising has stalled – there's been nothing since a USD 35m Series C extension in early 2020 – and Udesk is said to have lost ground to rival player Sobot.

Yunqi Partners backed Sobot in 2018, reasoning that a 2B start-up with a strong product could close the gap because there isn't the same high-cash burn-equals-scale philosophy as in 2C. According to Michael Mao, a co-founder at Yunqi, the firm has backed several 2B companies that have risen from second or third position to lead their respective segments.

Sobot recently raised a USD 100m Series D round led by SoftBank Vision Fund 2. Yi Xu, the company's co-founder and CEO, declined to discuss Udesk, but he emphasised that achieving efficiency is essential to survival.

"Lots of businesses decline after raising lots of money," Xu said. "It's often an efficiency issue. They expand aggressively, investing substantial sums while HR efficiency drops sharply. We hope to get the most out of every single dollar and we will try our best not to fall into such a trap."

A unicorn founder added that, though he regrets raising early rounds at low valuations, tight liquidity offered advantages as well. "For example, if I raised CNY 30m in the first round, I might not have been able to make good use of it," he said.

Malign influence?

Often, large equity cheques are accompanied by expectations that the recipients should scale rapidly. These expectations can be misaligned with the realities of the target industry. If the obstacles to growth are structural, rather than just financial, throwing capital at a company may result in a poorer customer experience. Similarly, getting too much money too soon can exacerbate any pre-existing weaknesses in a business model.

One founder of a software-as-a-service (SaaS) provider recalls taking money from a large investor at a high valuation and then being urged to initiate an aggressive product line expansion. The number of employees grew threefold in the space of three months.

It was a classic case of high cash-burn, mobile-internet wisdom meets steady enterprise services-oriented business model. And it left the founder in a bind.

A sharp increase in revenue could be achieved by providing customized solutions for large corporates, but this would mean lower margins and a fundamentally different economic model. Alternatively, the company could embark on a marketing blitz intended to attract small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). However, this segment is blighted by low survival rates and a general unwillingness to pay for SaaS subscriptions.

The money burned out quickly. When the start-up returned to market in search of additional funding, it failed to find any VC backers.

"There are numerous so-called small and beautiful high-quality companies that can grow 30-50% each year, but they are thrown into the air by radical VCs that come in with large amounts of money and demand 100-200% growth. This disturbs development rhythm and can result in a start-up burning to death," said one investor. "It happens every day."

The same mobile-internet logic is applied to late-stage rounds when large investors pay USD 100m for 20% interests in companies that, prior to their arrival, might only be valued at USD 300m. The goal, as the investor puts it, is to "quickly acquire monopoly status," thereby justifying an even larger jump in valuation.

Start-ups that want to develop at their own pace need early-stage investors that are familiar with the industry, business model, and management team. They can make assessments on what is right for a start-up at a given point in time – considering internal and external factors – and provide counsel accordingly.

"Even when I talk to friends who run start-ups, I advise them to initial funding from individuals they trust rather than picking investors based on brand name," said Wei Zhou, founding and managing partner of China Creation Ventures (CCV).

Tough on terms

A common misconception among founders, according to Zhou, is that they should take money from large investors as soon as possible. It makes for speedy fundraising – one player accounts for the bulk of the equity – and those investors can support subsequent rounds if other backers don't come forward. But these relationships are fraught with difficulty.

Relying on a single existing investor leads to concentration and conflict of interest issues: they might pull out completely or insist on pricing and terms for a follow-on that are punitive to founders. However, these problems may exist even when a large investor is not the sole participant in a funding round but wields its outsize influence over the process.

They are likely to demand a high degree of downside protection, including representations, warranties, and indemnities made by the founders in person rather than by the company. Founders might also be asked to stand behind a redemption right, with a relatively low trigger threshold, although in practical terms, it is often hard to execute on these.

Then there are veto rights, which could be used to block exits or fundraising. Whereas in the US preferred shareholders vote on decisions as a single asset class, with a simple majority prevailing, in China veto rights can often be exercised by just one series of investors or by every lead investor or every material investor. This makes corporate governance extremely challenging.

"For example, investors at the very early stage want to exit earlier, while investors in the later rounds have more time to achieve an exit, and have a higher target valuation," said Chou of Morrison & Foerster. "Granting veto right to individual investors across the cap table can bog down a company's ability to be able to make critical decisions in a fast-moving and competitive market."

PVP's Zou plays down the conflict-of-interest concerns, noting that funds within multi-strategy firms have independent decision-making processes and pricing mechanisms. His view is that entrepreneurs and investors should be more "open-minded and far-sighted," and recognise that integration of private equity and venture capital is an established trend.

Nevertheless, when it comes to constructing an investor base, Wayne Shiong, a partner at China Growth Capital, advocates bringing in investors focused on different stages in an orderly manner. This reduces the likelihood of being hamstrung by internal disagreements and makes it easier to recruit lead investors for subsequent rounds.

"If you take Tiger Global's money at the seed stage, then you basically lose a lead investor for your Series D," said Shiong. "There are limited investors that can take the lead in a Series D, but many choices for early rounds."

Entrepreneurial instincts

First-time entrepreneurs often struggle to grasp the nuances of funding rounds. The overriding impulse is to take what money is available, almost regardless of the source, especially in the nascent stages of development when business models are unproven and an element of uncertainty remains.

"You need to ensure survival. Provided the business develops well, other issues regarding valuations or investor backgrounds are only theoretical discussions," said Guobiao Deng, founder and CEO of XTransfer, a cross-border payment service provider, which closed a USD 138m Series D round last year led by US-based D1 Capital Partners.

This view is echoed by Chunquan Ma, co-founder and CEO of reimbursement platform Ekuaibao, who argues that primary concern is having capital at times when it suits the rhythm of the business. SoftBank Vision Fund 2 led a USD 155m Series D for Ekuaibao last year, on the back of a less than two-month due diligence process.

"The ideal scenario is you raise early rounds and then survive on your own like Google. In such case, a high valuation is okay," said Ma. "But if you need to raise money every year, you must be mindful of the valuation. If it's too high, a down round might follow. You have a kind of road map with milestones you need to hit to achieve different valuations and continue an upward trajectory."

Milestones – and the numbers that sit behind them – help capture a key difference between early-stage and late-stage investors. The former are motivated by ideas, technologies, and visionary founders, while the latter draw comfort from conformity with traditional evaluation metrics. This impacts their traditional entry points and how they perceive the needs of portfolio companies.

As these sometimes-conflicting philosophies and agendas overlap at an earlier point in a start-up's life, friction is inevitable. Ultimately, though, both sides want to see a return. It is ironic that down rounds sometimes come after an important milestone is achieved – the commercial landing of a debut product – but it says everything about the confusion of hype and reality.

"If you ride a megatrend that everyone is following but doesn't make income for a long time, investors might continue to support you even if the valuation is very high," said Wei Cai, a partner at Lightspeed China Partners. "But if your final product comes out and generates revenue, but your overall business growth doesn't keep pace with your valuation, it will lead to fundraising problems."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.