India consumer media: Showtime

Investors navigate slim margins and a complex cultural landscape as new digital channels help Indian media rebound from COVID-19. Sector leaders are flirting with global expansion, but is it too early?

No category illustrates the temptations and challenges of Indian media as concisely as over-the-top (OTT) video streaming. In the past two years, an oligarchy of Disney+ Hotstar, Netflix, and Amazon Prime have scaled rapidly, taking between 80-90% of the market. But the market has proven deceptively shallow.

"The biggest mistake investors make is assuming there are 1.3bn Indians who can pay for subscriptions. Some of them target subscription models at massive scale, but there are around 40-50 million households in that market," Ashish Pherwani, media and entertainment (M&E) leader for EY India, said. "It will probably take four to five years for the market to reach 100m paying subscribers. Other than that, there's so much scale to be had."

With only about 4.5m paid subscribers versus Disney's 36m, Netflix is feeling the pressure acutely. CEO Reed Hastings recently called traction in India "frustrating," but pledged to continue leaning into the country. This will put the company's price point and positioning under the microscope, but for private equity and venture capital, there are more fundamental lessons to be learned.

Advertising, not subscriptions, remains king in terms of media monetisation in India, although there is distinct promise in gaming-style in-app purchases and retail-related crossovers including social commerce. Overall, the models are unproven with only a few digital players recognised as achieving revenue at scale and little clarity about how the paradigm will evolve.

The lack of monetisation is where the appeal lies, however. Indian M&E is only an approximately USD 18bn industry despite having an audience of some 600m video-consuming internet users. Advertising expenditure is particularly under-indexed, representing only 0.3% of GDP in India in 2020, a figure tipped to claw up to 0.4% by 2025. China and Japan are currently around 1%.

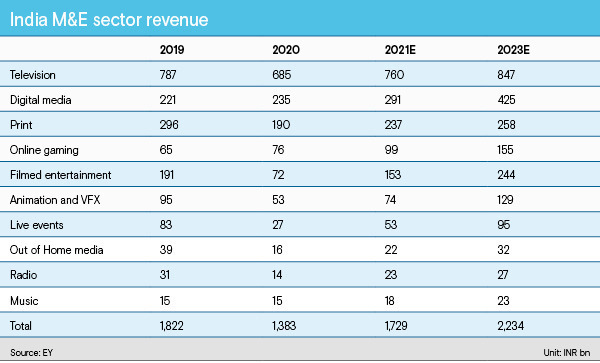

EY estimates the size of India's M&E sector will reach a record high of INR 2.2trn next year, up 17% versus 2020. The strongest performing segments will be live events, filmed entertainment, and animation and visual effects, which are expected to see growth of up to 52% between 2020 and 2023.

Streaming success

Television remains in the top spot at INR 760bn, but the pandemic saw digital media overtake print to create what is expected to be a INR 4.2bn industry by next year. Most of the upside here is in video; India is a predominantly Android mobile market, featuring pre-loaded YouTube apps. YouTube attracts 500m monthly visitors and has taken on a role as everyday all-purpose search engine.

"As a format, we are very bullish on short-video. We believe it has potential to be as ubiquitous as a DM app like WhatsApp," said ShareChat CEO Ankush Sachdeva.

ShareChat launched in 2015 after observing that the first thing consumed when people go online is content; financial services and commerce come later. The company's namesake social media app has various messaging, content sharing, and chatroom functions in 15 vernacular languages with a strong focus on artificial intelligence-power content recommendation.

By mid-2020, political tensions with China saw India ban short-video platform TikTok, the dominant player in this space locally with some 200m users. Of the various local start-ups aiming to fill the hole, ShareChat and Trell – which brands itself as India's leading lifestyle video app, vlog and blog – gained the most traction.

ShareChat has raised more than USD 950m across three rounds during this period, including a USD 266m round from the likes of Alkeon Capital, Moore Strategic Ventures, and Temasek Holdings at a valuation of USD 3.7bn in December. Its Moj short-video service, scrambled in the wake of the TikTok ban, has already reached the size of the flagship app. They now have 300m monthly active users (MAUs) combined.

In the meantime, there has also been a surge in the news app segment, where Dailyhunt peeled away from the pack in August last year, achieving a valuation of USD 3bn on closing a USD 450m round that featured The Carlyle Group.

Dailyhunt also offers a short-video service called Josh which had amassed more than 115m MAUs across 14 Indian languages as of the investment. This diversification is sometimes attributed to the inherent challenges of the category.

"News is not a high-margin business. About 70% of the revenue goes to the news owners and news creators. That's the challenge for most of the aggregation businesses in India," one investor said.

The common themes for success across the digital M&E space is attention to local languages and creativity in terms of monetisation models such as virtual gifting and tipping, in-app purchasing, and social commerce. ShareChat claims its virtual gifting function has grown 5x since its launch in January 2021.

International angle

The question remains to what extent the arrival of global investors will translate into global footprints.

TikTok's expansion success in the US, for example, was realised by targeting the Chinese diaspora and parlaying the initial demand to the broader market. ShareChat envisages a similar story in the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East, recognising opportunities to re-use existing content and pull in a wider audience for local creators.

"To be competitive in any foreign country the fundamentals will remain the same. Can you beat world class companies in ranking and relevance? Winning a market as competitive as India will give us more confidence to venture outside. For the next 1-2 years, we want to stay heads down [in India] and focus on the fundamentals of the business. I firmly believe that if we can win in India we can win in any part of the world," Sachdeva said.

Mayank Khanduja, a partner at Elevation Capital who led his firm's investment in ShareChat, sees audio as a more immediate opportunity for overseas adventures than video, largely because of a lack of dominant incumbents in the most interesting expansion markets.

He observes that active after-dinner listening to episodic content in the home is now outpacing passive drive-time consumption, especially in lower-tier cities and towns. The trick to this space will be eschewing the typical Indian production style of cranking out high volumes of lower quality content.

"A pure UGC [user-generated content] play may not work on audio. You need to moderate it yet not to the point that your own production capacity becomes the bottleneck. We're investing a team that has found a beautiful solution in scaling content in high quality," Khanduja said.

"If you're able to crack high-quality content creation at scale, it doesn't really matter which geography you attack. I definitely see very high potential for international expansion in audio in Southeast Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa, wherever the sensibilities are similar about consuming engaging episodic content. That's the thesis we're underwriting."

Across formats, digital media appears primed to leverage a range of Indian strengths in internationalisation. There is the natural facility with English, the large domestic market springboard, and the reputation as a behind-the-camera technology supplier.

Still, many investors see global expansion as a premature opportunity. Other segments are expected to go global first, led by software-as-a-service (SaaS), which is already an established cross-border play. Potential followers include cryptocurrency, education technology, and B2B services.

"For me, consumer media is a bit further behind because it's so context specific with language, cultural nuances, and accents. That's very hard to do abroad," said Dev Khare, a partner at ShareChat investor Lightspeed India Partners.

"Our advice is not to sell Indian content into international markets, other than if you're just trying to monetise 20% more with the Indian diaspora. If you've invented a format, use that by all means. It might be successful in the US – but use American actors, accents, and situations. You can't have a story about cricket suddenly get big in the US."

Rules, exceptions

Lightspeed's other key media holding is Pocket FM, said to be the largest audio OTT platform in India with some 40m downloads. In December, Pocket raised USD 22.4m in Series B funding led by Lightspeed with support from Times Group and unveiled plans to enter the US. This coincided with a partnership with US-based Triton Digital, which specialises in podcast advertising services.

Khare described Pocket as one of only a few Indian media outlets to gain traction overseas, while stressing that Lightspeed's investment in the company was not based on expectations of international growth. Indeed, 57.6m Indians were consuming podcasts on at least a monthly basis as of 2020, according to KPMG, making it the third largest podcast market after the US and China.

The most interesting aspect of the Pocket-Triton tie-up, however, is that it probably foreshadows India's role in global digital media in reverse. Rather than providing original content and intellectual property (IP) with support from foreign technical partners, India will be the technical partner for foreign producers.

Lightspeed has exposure to this idea via Pepper Content, a content production outsourcing provider able to supply everything from blogposts and videos to infographics and text translations. The leading player is arguably Amagi, a SaaS provider for traditional TV and OTT broadcasters that claims an audience of more than 2bn people. It has raised around USD 170m from the likes of Accel and Emerald Media, a KKR-backed platform.

WEH Ventures, a seed-stage investor that has made media a feature of its early activity, is confident about consumer-focused models but cautious regarding their potential to go global. The firm's portfolio includes Trell and Pratilipi, a literature, comics, and audio storytelling platform focused on user-generated content with service in 12 Indian languages.

Pratilipi has raised USD 79m to date from the likes of Times Group and China's Qiming Venture Partners and Tencent Holdings. Korean gaming studio Krafton led a USD 48m Series D last year. The plan is to transpose the company's IP into gaming formats for international audiences. "They'll do a little bit of global, but gradually, not crazily," said Deepak Gupta, general partner at WEH.

Gupta and Khare see significant echoes of China's consumer media story, comparing Pocket FM to Ximalaya, Pratilipi to China Literature, and Trell – which is gearing toward e-commerce adjacencies – to Xiaohongshu. China Literature raised USD 1.1bn in a Hong Kong IPO in 2017, while Xiaohongshu was valued at USD 20bn in a USD 500m round last year.

Meanwhile, Ximalaya exemplifies the difficulty of replicating a TikTok-style breakout. The podcast platform had built up an ex-China audience of 35m and raised more than USD 600m in private funding before abandoning a US IPO in September as tensions between Beijing and Washington around data-sensitive business models ramped up. It has since targeted a Hong Kong listing.

"The China parallels are important to investors to take a leap of faith because before 2016, we didn't have those models," Gupta said, flagging the two countries' more crucial similarities in terms of social confidence.

"As India's economy became stronger, there was a nationalist feeling, and that happed in China too. There's a pride in the culture that seeps through over time, and it becomes cool to consume media in your own language, which was not the case for my generation. In a tier-one English-educated society, MTV was cool. But that was a long time ago."

Content for kids

Some of the best case-studies in Indian digital consumer media creating global brands are in children's YouTube channels such as ChuChu TV, which tracks its US visits in the billions. This engagement model is about name recognition, not reliable revenue; the idea being that the exposure can lead to more lucrative contracts with traditional TV and OTTs.

Cosmos-Maya, an animation studio NewQuest Capital acquired from Emerald Media last year for a reported USD 90m, is going down this path with WowKidz, a network of 34 YouTube channels where original IP such as Vir the Robot Boy has clocked 20bn views, 30% of which are outside of India. Vir is said to still get 500m views a month despite no new episodes being produced since 2016.

The traction has translated into deals with Disney+, Amazon Prime, and Zee5, a local OTT. Similarly, an original title called Eena Meena Deeka, which has dominated the YouTube kids' channel of Canada-based WildBrain, is now receiving international co-financing for its third season with support from Sony. It will be re-launched with an English name, Ding Dong Bell.

Devdatta Potnis, a senior vice president in charge of revenue and corporate strategy at Cosmos Maya, likens Indian studios creating global content to a fast food restaurant putting a gourmet dish on the menu. One product will require an overhaul of operational processes and the economic returns may not be worth it.

"India has about 400m kids, and we have a 50-60% market share of the original content that goes to these kids. That's a value proposition that's only going to grow over the years. We don't want to compromise it. We will have our global ambitions, but from a management bandwidth standpoint, I wouldn't assign more than 10% to that," Potnis said.

Cartoons appear to be the most conducive category to international expansion. Dubbing is easy, and the hijinks are culturally universal. But prioritising the global stage over local success can be a dangerous road for Indian producers.

For example, Mighty Little Bheem, a title by Green Gold Animation, received global recognition as Netflix's first Indian cartoon, but this came at the cost of a local audience. The locally struggling Netflix remains the only service broadcasting the show.

"We're very clear that we have international aspirations, but we'll not let go of our Indian brand advantage that we have with our IPs," Potnis added. "Today, when we are planning a spinoff of Vir, we are getting an American writer for that global kind of storytelling, but we're also getting a creator out of India, so the soul is retained."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.