China IPOs: Offshore angst

Private equity exit timelines were thrown into disarray last year when US IPOs abruptly stopped. Regulators have offered some clarity, but investors are unsure when – or if – the magic will return

The path connecting Beijing and Shanghai with the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and NASDAQ is well-trod. More than 200 private equity-backed companies have completed the journey since 2000, when the variable interest entity (VIE) structure emerged as a means for foreign investors to access Chinese industries where their direct involvement is forbidden. IPO proceeds amount to USD 80bn.

Without US offerings, the first generation of China VC investors would have limited track records. Now, though, the NYSE-NASDAQ route is clouded by regulatory uncertainty, and they are busy repositioning start-ups to list in Hong Kong.

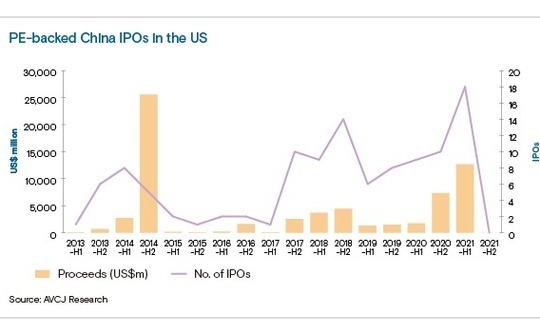

The turnaround has been dramatic. In the first half of 2021, 18 PE-backed Chinese companies raised USD 12.7bn through US IPOs, a level not seen since Alibaba Group went public in 2014. It extended an upward streak dating back two years. In the second half of 2021, the market ground to a halt.

It comes on top of additional regulatory hurdles around data privacy and the lingering possibility of forced de-listings in the US over an audit dispute with China. Bankers and lawyers are unsure about the viability of the US listing route, even if it remains theoretically open.

"Eight or nine months ago, when I spoke to industry participants who really focus on the US market, they believed there would be some kind of compromise on the audit issue. Now, most people think it would be difficult for either side to compromise, given the current level of tension between the two governments," said Marcia Ellis, global chair of the private equity group at Morrison & Foerster.

A surprising dovetail

The audit issue has been a slow burner, but finally, it may be about to go full blaze. Late last year, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) finalized implementation guidelines for legislation endorsing the removal of Chinese companies from US bourses if they block inspections by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). It effectively started a three-year countdown.

Bruce Pang, head of macro and strategic research at China Renaissance Securities, estimates de-listings of the 250 Chinese companies currently trading on US exchanges could start in 2024. If regulators take a harder line, the deadline shortens by 12 months.

An economist at a state-owned Chinese bank added that few investors took the prospect seriously until the Chinese government dovetailed with US regulators and encouraged local companies to avoid New York IPOs. He contends this was a pre-emptive action to address de-listing risk, but there were other motivating factors.

The Cyberspace Administration Office (CAO) subsequently issued draft measures requiring local companies holding personal information on more than one million users to report to relevant agencies about the data security before pursuing offshore IPOs. Didi's share price hasn't recovered and the company announced in December it would vacate NYSE and look to list in Hong Kong.

A Shanghai-based investor told AVCJ last year that such reviews are lengthy and involve a dozen different agencies, including the National Security Bureau. Asked for an update, the investor reaffirmed this assessment, and added that even business services companies that collect no end-consumer data are being caught in the net.

"During the process, relevant laws, provisions and regulations are not specified. Any of these regulators can hit the pause button or call off the listing process," he said.

Long waits for reviews, coupled with the general sense of process uncertainty, has already seen multiple PE-backed companies abandon planned US IPOs. They include podcasting platform Ximalaya, which has since filed to list in Hong Kong. The likes of Linkdoc, Daojia, Xiaohongshu, Keep, and Hellobike are also said to have turned their backs on New York.

VIE still viable?

These actions predated the China Securities Regulatory Commission's (CSRC) proposed offshore listing rules, which were released on Christmas Eve. Domestic companies will not have to seek approval for IPOs and documentation will not be subject to formal vetting, but financial penalties will be imposed for a failure to file or for disclosing significant false information.

"In recent years, there have been frauds such as Luckin Coffee, but the domestic securities regulator was unable to directly supervise or intervene. These frauds have damaged the international reputation of Chinese companies," said Zheng Yu, a senior partner at JT&N, a local law firm.

While this aspect of the rules is not being challenged by industry participants, various others are. VIEs, inevitably, feature among them.

One concern is that ownership restrictions applied to domestic listings will filter through to offshore offerings. At present, the foreign investment ceiling for A-share companies is 30%, with individual players capped at 10%. Pang of China Renaissance suggested that regulators might take a similar approach to VIEs, which are onshore structures.

But on a broader level, the viability of the VIE is being questioned in part because of US regulatory intervention. The SEC now requires Chinese companies to clearly disclose VIEs, including the relationship between the listed entity and entities responsible for business operations. They must outline the risks associated with VIEs and the implications of contracts being deemed unenforceable.

The CSRC responded by stating that companies with VIE structures can list overseas provided they meet compliance requirements and subject to domestic laws. It offered a degree of reassurance, but the draft regulations do not go into any detail on these two conditions.

Betty Yap, a partner and global co-head of the financial sponsor group at Linklaters, suggested that the compliance requirement relates to data security. Meanwhile, the reference to domestic laws is open to even wider interpretation.

"There is a big question mark as to what this is getting at as a VIE is sometimes seen as a way to circumvent foreign ownership restrictions and may not be seen as fully compliant with domestic laws," she said.

"Can a VIE be considered as compliant with domestic laws? Does it depend on the structure? Can a certain amount of restructuring make it work? Does it depend on the investor base, for example, is the VIE actually controlled by PRC nationals?"

Meet the meddlers

Once regulations come into force, implementation guidelines are introduced, which usually help distil vague policy language into meaningful action points. Nevertheless, industry participants claim uneasiness over the authorities' propensity to meddle.

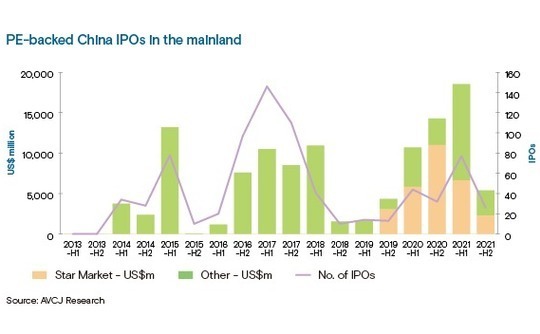

Offshore listings are subject to a lighter-touch, registration-based system intended to allow speedy passage to market. A similar system has been introduced for IPOs on certain mainland bourses in recent years, but it appears the CSRC cannot help itself.

"The regulator is also supposed to step back in Shanghai's Star Market and Shenzhen's ChiNext, merely ensuring the accuracy and completeness of an IPO candidate's filing. But a lot of companies have been told to shelve their IPO plans or have withdrawn applications," said one banker.

"We cannot say it will happen in exactly the same way for VIE-structured companies, but we have reason to worry about their chances of survival in the face of new rules and approval requirements."

Moreover, the proliferation of VIEs in the consumer internet space – direct foreign ownership is severely limited in the tech sector – means most companies will have to undergo data security reviews as well. "Those with fewer than one million users are unlikely to meet IPO requirements for overseas markets [because they don't have the scale]," a second banker added.

Not everyone is willing to write off the structure. An alternative perspective on China's bid to rein in offshore IPOs is that VIEs aren't really in the crosshairs. In fact, it is all about data and VIEs are more like collateral damage – because they are used by a lot of Chinese companies listed in the US.

"You should not mistake and think that this is an attack on VIE structures," argued Ellis of Morrison & Foerster. "Based on what the CSRC has said, and all kinds of other things that have happened in the last few years, we believe the government has accepted VIE structures and can live with them."

This view is endorsed by Xiaofeng Wu, a founding partner at Bright Capital, which specialises in early-stage consumer-technology investments. He noted that the regulator's intentions can be read in the decision to allow companies with VIEs to access the A-share market. Electronic scooter brand Segway-Ninebot was the first to achieve this in 2020 on completing a Star Market listing.

Vague and vaguer

Positives are also drawn from the final version of the cybersecurity review requirements, which take a softer line than outlined in the draft. Whereas originally it applied to all "data operators" with more than one million users, now it is "network platform operators." This subtle shift means the likes of hotel loyalty programs are not subject to review.

Yap of Linklaters cautions that the term "network platform operator" has yet to be properly defined. At the same time, companies deemed significant to national security must be reviewed even if they don't meet the one-million-user threshold. "It does give the government quite a lot of discretion, which I think is intentional, so it can assess on a case-by-case basis," she said.

Another vague area in the cybersecurity ordinance concerns Hong Kong and to what extent it is considered a "foreign" authority. Most investors are working to the assumption that reviews will not be required. Ximalaya has yet to be called for inspection, one of the company's backers said.

A Beijing-based LP added that Didi would also be exempt. "Such a special arrangement sends a very positive signal to investors and the overall market," the LP said.

However, China Renaissance's Pang believes that, in practice, relevant companies pursuing Hong Kong IPOs will still have to undergo a review. However, the Chinese authorities will make it a more streamlined and simplified procedure in order to support the special administrative region as a financial hub.

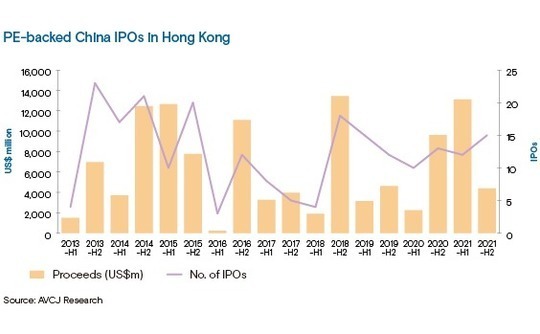

The consensus view is that regulatory actions taken in China and the US have effectively elevated Hong Kong to the default option for offshore IPOs. This is already reflected in the exit provisions included in investment agreements.

In addition, there is an expectation that more US-listed players will follow Didi's lead and seek to move to Hong Kong. To date, 19 companies have opted for US-Hong Kong dual listings or completed secondary listings in Hong Kong. The territory's exchange is looking to facilitate full transitions, notably reducing the volume requirements for re-listings.

"Weighted voting rights provisions have also become more flexible because they no longer need to apply only to ‘innovative' companies if those companies are returning from the US," said Zhong Jin, a managing director and deputy head of growth enterprise investment banking at China International Capital Corporation (CICC).

According to CICC, 37 US-listed Chinese companies would meet requirements to re-list in Hong Kong. It is uncertain what route they might take to get there. A take-private is one of several options. Centurium Capital led such a transaction for China Biologic Products last year, and Zhixing Chen a managing director at the private equity firm, told AVCJ that a Hong Kong IPO is a logical next step.

"This is the best and most convenient way, without any structural adjustments. The current shareholders are all US dollar-denominated funds. From an investor perspective, future liquidity and exits may be easier in Hong Kong," he said. "But we do not rule out an A-share listing in the future."

Smaller companies that are unable to list directly could become merger targets for entities that list in Hong Kong under the territory's new special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) regime. Industry participants expect helping businesses complete the final leg of the US-Hong Kong journey to become a prevalent SPAC theme.

Clarity to come

These transitions are not necessarily straightforward because they involve adopting a different corporate mindset. Hong Kong is still a compliance-based system, so listing candidates must address certain deficiencies. In the US, disclosure of the risks these present is enough. For example, a ride-hailing business wouldn't be accepted in Hong Kong without a full set of local operating licenses.

Ellis of Morrison & Foerster said the CSRC's draft offshore listing rules hint at a requirement for complete compliance. This would remove the distinction between Hong Kong and the US – and essentially make it challenging for unconventional or less well understood Chinese companies to list.

"If you are in a disruptive sector, doing something that hasn't been done before and the regulatory framework is non-existent," she said. "For that type of business, it would be hard to list anywhere."

The picture will become clearer as regulators issue more guidance and companies start to test the water in greater numbers. Much the same can be said of the wider policy landscape in China, which was significantly altered in 2021. The technology sector was a particular target and investors are still trying to map out the longer-term implications.

Although the clarity around IPOs has yet to reach an optimal level, China Renaissance's Pang believes the government is now doing more to manage the pace and intensity of its initiatives.

"Officials have started to communicate more effectively with the market about the motives and rationale behind the regulatory push and telegraphing future hotspots," he said. "This is because, in our view, investor concerns may be driven less by the substance of proposed regulations and more by communication."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.