China regulation: Shock and awe

A raft of rules, largely targeting the technology sector, has challenged business cases and thwarted exits in China. It is also contributing to tweaks in investment strategy

"We were supposed to do another close at the end of November, but obviously that's been delayed," one China VC manager remarks. "LPs say they need to review their China strategy. Some say they will do it next month; others say by the end of the year or the first quarter of next year. Everything is a bit up in the air."

This is a typical response from the fundraising trail. Four venture capital firms told AVCJ that progress on their latest US dollar-denominated offerings has been delayed by LPs putting a hold on China commitments. Inertia extends into the private equity space, with at least one large manager extending its fundraising period, according to sources close to the situation.

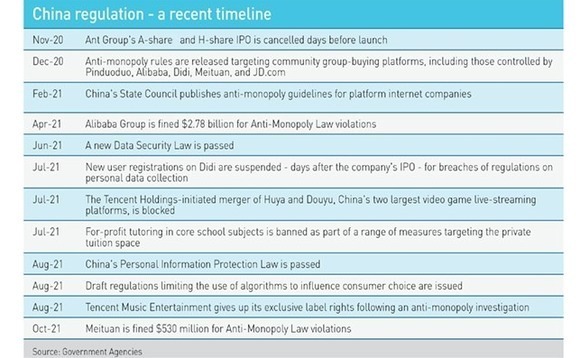

The cause is regulatory uncertainty that, in the space of less than a year, has spread across the technology sector into various consumer-facing segments of China's economy. Anti-monopoly investigations targeting top internet companies, a redrawing of the commercial guidelines for private education, and a sweeping data privacy law are among the highlights.

With investment theses being questioned and paths to liquidity unclear, LPs are reluctant to pull the trigger. One placement agent observes that he hasn't seen it this bad since the global financial crisis.

"There is enormous reluctance to jump into new relationships right now. Even on the re-ups, a lot of US institutions are talking at length to their partners about whether this is a pause, or it requires some sector rotation, and some adjustment by the GP," adds Edward J. Grefenstette, president, CEO, and CIO of The Dietrich Foundation.

The foundation, which has significant China exposure, remains cautiously bullish on the country's medium to long-term prospects. Indeed, it believes the regulatory changes, when viewed as part of a cohesive social agenda, could prove beneficial.

While the continued relevance and attractiveness of China to private equity is not in dispute – even the China VC manager notes an improvement in sentiment in the last few weeks – recent developments point to potential shifts in strategy. As some sectors face regulatory headwinds, others enjoy policy tailwinds, and investors are repositioning themselves accordingly.

"This doesn't mean we won't invest, rather the level of scrutiny and the level of vetting is going to be at a much higher level," says Hans Wang, who leads the Greater China team at CVC Capital Partners, while noting that the firm's investments haven't been impacted by regulatory changes.

"In addition, we are probably going to have to pivot our sector focus and strategy, because the universe of investable sectors narrowed," says Wang.

Full court press

Industry participants stress that they were not caught off guard by the nature of the regulatory intervention, rather the speed and scale. One China-focused private equity investor highlights the number of simultaneous actions, including the decision not to rescue China Evergrande, a casualty of a drawn-out crackdown on overleveraged real estate developers.

"This is a low point when it comes to global demand for China equities, probably the lowest point in the last 10 years," he adds, a conclusion reflected in public markets. The CSI Overseas China Internet Index peaked at 14,735 points in February; it is now languishing at around 6,700.

Shares in Alibaba Group, Tencent Holdings, and Meituan – early targets for the regulators, first through Ant Group's canceled IPO, then through anti-monopoly investigations – are down 40% on their January peaks. Recent IPO darlings have also taken a hit, including those directly impacted by regulation, like short video platform Kuaishou, and those not, such as chipmaker Cambricon.

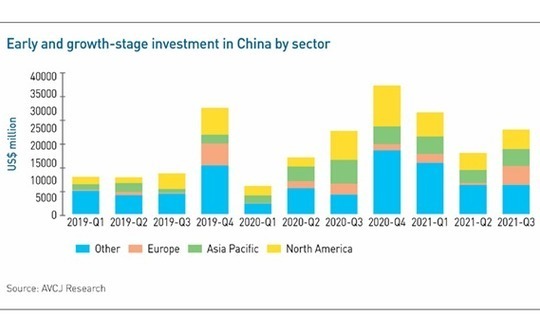

In the private markets, early and growth-stage investment in the technology sector slumped from $14.8 billion in the first quarter to $8.4 billion in the second and remained at that level in the third. As recently as the final three months of 2020, it was at a record high.

When investors are asked to name a sector in which they were previously active but would now avoid, education is the typical answer. As for existing positions, a string of write-offs is expected, although some companies are trying to pivot into school services or education hardware.

Exits have been complicated for performing businesses that are not directly in the firing line. Lincoln Pan, a partner at PAG, told the AVCJ Australia Forum that investors should seek exits as quickly as possible. However, he noted that the listing or secondary sale options envisaged for a kindergarten operator PAG owns are no longer viable. A structured solution seems most likely.

"The risk in the market has fundamentally changed," Pan added. "Certainly, in the next 12-18 months, with a lack of guideposts in terms of where regulations are coming, GPs need to be extremely careful on valuations and on underwriting."

Nevertheless, several investors claim to have anticipated government intervention. They cite social problems created by the industry's rapid growth – most parents hailed the change for liberating their children from endless after-school courses – which was in turn fueled by subsidy-driven business models that prioritized market share head of long-term sustainability.

Liyong Zhou, a general manager in the VC unit of Shanghai STVC Group, a state-backed LPs, tells AVCJ he turned down several educational funds in previous years. "I was very opposed to investing in after-school training from day one," he says. "Off-campus training cost a lot, creates anxiety, and many excellent teachers in public schools have been dug out by these training institutions."

Meanwhile, Jinjian Zhang, whose track record at Trustbridge Partners was based on education investments, chose to avoid the sector when he spun out to launch Vitalbridge in 2019. The warning signs were there as early as 2019, he notes, with customer acquisition costs mounting, ROI [return on investment] below 100%, yet stubbornly high valuations.

Vitalbridge also saw demographic pressure. China's birth rate has fallen for four consecutive years, reaching a 58-year low in 2020. Reversing this trend means reducing the cost of raising a child, with education and healthcare the key pressure points. "We felt that the regulation would come eventually, but we couldn't foresee when and how," says Zhang.

Didi debacle

The second regulatory intervention of note is the investigation of ride-hailing giant Didi over data privacy violations days after its US IPO in June. This laid the ground for additional approvals for certain companies seeking to list overseas.

China's Data Security Law was passed on June 10 and scheduled to come into force on September 1. Didi, as well as online job recruiter Boss Zhipin and trucking platform Manbang, listed in between these dates. Didi's IPO was extremely low-key. There was no ceremony, no speeches, and employees were forbidden to comment on the event. It suggested a degree of regulatory sensitivity.

An investigation by the Cyberspace Administration Office (CAO) soon followed, during which new user registrations were suspended. Manbang and Boss Zhipin were later also placed under review.

On July 10, the CAO issued draft measures requiring local companies holding personal information on more than one million users – Didi has 377 million – to report to relevant agencies about the data security before pursuing an IPO on an offshore exchange.

"In terms of exits, we wouldn't be looking at anything heavily reliant on the US," says CVC's Wang. "Overall, I would describe it as very much a China-contained thesis."

Others are less equivocal about the changes. Doris Guo, a partner at Adams Street Partners, told the AVCJ China Forum that it is just another part of the listing process, not unlike an audit. She doesn't expect the security review to "become a threshold for listing" and links the recent slowdown in IPOs to uncertainty ahead of final details being released.

Moreover, other industry participants claim that China's approach is reasonable when viewed in the context of US demands that foreign chipmakers like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC) and Samsung Electronics disclose supply chain information. TSMC has said that it cannot disclose confidential information on customers.

"Even if China didn't issue the data review measures, investors should worry about future IPOs by Chinese portfolio companies. The US has strengthened supervision, and it may ask companies to disclose even more information in future. To some extent, in order to preemptively avoid these potential risks, China has tightened rule on its side," says Fielding Chen, an economist at China Construction Bank.

Competitive dynamics

An intriguing byproduct of Didi's misfortune is the way in which prospective competitors are seeking to capitalize on it. Two ride-hailing companies, Caocao Chuxing and T3, have raised sizeable funding rounds in recent months, largely from strategic and state-backed investors. T3 has made clear that eating into Didi's market share is its goal.

While this might not be exactly how Beijing envisaged it playing out, creating a more level playing field within the technology sector is a key driver of the regulatory blitz.

The antimonopoly investigations saw fines imposed on Alibaba and Meituan for insisting that merchants use them as exclusive distributors. Another investigation resulted in Tencent Music Entertainment giving up its exclusive label rights, while a Tencent-initiated merger of Huya and Douyu – China's largest video game live-streaming platforms – was blocked.

One perspective is that these measures are "anti-entrepreneur" or even "anti-technology." Another is that leading technology companies have been allowed to roam too freely for too long, and that curbing their influence benefits consumers and competitors.

Alibaba and Tencent are now looking into how they can open their ecosystems to each other, allowing WeChat Pay to be used on Taobao and Alibaba services to launch WeChat mini-programs. Their recent investment in social e-commerce platform Xiaohongshu, suggests an end to the practice of taking capital from either Alibaba or Tencent, but never both.

"Recently we have seen changes in the strategic investment and M&A processes of the internet giants. They are more open-minded, no longer pursuing control and market share, more willing to create synergies and inject resources in accordance with regulations," says Daisy Cai, a general partner and head of China at B Capital Group.

"In the long run, the reduction of defensive acquisitions may even result in a larger private equity M&A and secondary markets."

At the same time, the notion of curbing influence has assumed specific importance with the release of draft regulations for algorithms, often used by internet platforms to recommend products. It is unclear how these rules will be implemented but a Beijing-based early-stage investor notes that artificial intelligence (AI) start-ups have suspended fundraising.

The concern is that regulators will take a heavy-handed approach and wipe out AI as an investable proposition, much as they did with large swathes of private education.

"AI is not a separate sector, it's a tool for many if not all industries. Regulators oversee the usage of data and algorithms to protect end consumers' interests and fair competition, not to hinder technology's development. AI is a key area of competition globally," says Jiawei Wu, a lawyer at Zhong Lun Law Firm.

Political angles

While China's approach to regulation may seem abrupt and arbitrary, the interventions of 2021 are connected by a single thread, which feeds into broader policy initiatives. The key themes, first outlined by President Xi Jinping, are a drive towards "common prosperity" and the "great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation."

Common prosperity is logically interpreted as wealth redistribution, and this is making its mark on the technology sector as companies pledge money to social causes. Steps are also being taken to improve employee welfare, with ByteDance and Tencent ending their infamous 12-hour day, six-day week, and Meituan guaranteeing a minimum wage and insurance cover for delivery staff.

In this context, reining in anti-competitive technology companies, curbing excesses in education, policing the use of personal information, and regulating algorithms could be seen as contributing to a society that is more equitable for consumers and a marketplace that is kinder to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Pointing to action taken against community group-buying platforms for anti-competitive behavior, J.P. Gan, founding partner at Ince Capital Partners, observes that it wasn't the subsidy-driven business models of market leaders that upset regulators as much as who was suffering as a result. "They were burning cash and hurting SMEs, that's why the government cracked down," he says.

Indeed, parallels are readily drawn between China's agenda and that of other countries. "What they are targeting is not dissimilar to what the US and Europe are doing on data privacy and making sure businesses are doing the right thing, as well as trying to grow," says Yar-Ping Soo, a partner at Adams Street Partners. "It's the structure of the government that's different. Things can be done faster."

The great rejuvenation is generally viewed as a reference to its international relations, specifically those with the US. The data privacy legislation is clearly designed to combat extra-territorial applications of other countries' laws and control the transfer of information overseas.

However, some investors present the broader package of regulations as a response to the US and the red lines it has drawn across trade, finance, and technology. Targeting consumer internet companies may support a strategic as well as a social agenda, by encouraging investment in higher-value core technology that addresses Beijing's desire for self-sufficiency.

"We can roughly divide technology firms into two categories: platform-based and hard-core technology-based. While hard-tech is its own barrier, platforms use scale and capital to set up barriers. They try to get to critical mass as quickly as possible to become the dominant player," explains China Construction Bank's Chen.

Deployment plans

Private equity investors as a group haven't abandoned the consumer internet segment – plenty of deals are still getting done – rather they are highly attuned to what plays into policy initiatives across different sectors. CVC's "China-contained thesis" includes pure domestic consumption opportunities, most likely those aimed at the broader middle class instead of the elite.

Within technology, nearly every investor is targeting domestic substitution, driven in part by US-China decoupling. China Renaissance is more specific, looking for areas in which local products are nearly on par with the imports they replace and may overtake them. Electric vehicles (EV) are a classic example, while also benefiting from the government's focus on climate and sustainability.

Capital is pouring into EV value chain deals, which include batteries, semiconductors, and spare parts. The emphasis on hard-tech dovetails with a similar deep-tech theme, contributing to a gradual but meaningful shift from B2C to B2B. Artificial intelligence, cloud infrastructure, semiconductors, and SaaS are hot commodities.

Venture capital investors began to diversify several years ago, driven by economic rationale – B2C was increasingly characterized by large platforms and expensive business models – more than regulation. Several VCs don't do any B2C, such as Yunqi Partners, Future Capital, Glory Ventures, and Ameba Capital. All have closed funds in recent months, despite the challenging environment.

In terms of early and growth-stage deal count, internet services – a rough proxy for consumer-facing – accounted for roughly half the China total through the middle of 2019. It then fell back and hasn't recovered. More recently, the same has happened in dollar value, as larger GPs get involved. The non-internet services share was 70% in the third quarter, up from 40% in the final quarter of 2020.

The implication is that, although overall China technology investment held steady in the third quarter, money was gravitating to new areas within the sector. Cleantech and renewable energy, which captures much of the EV value chain activity is $4.6 billion year-to-date, more than the previous four years combined.

Inevitably, it leads to concerns about valuations. "If something is not for the general good, you must be careful," says the China-focused buyout manager. "We invest in boring sectors that meet the fundamental needs of the people. Investing just because you think that's where the government wants you to invest can be problematic. People can forget about the business fundamentals."

SIDEBAR: Algorithm oversight

China recorded a global first in August by issuing proposed regulations for algorithmic recommendation technology. It is part of a broader effort to limit the power – and in this case influence – of internet companies. Investors had one obvious question: What does this mean for artificial intelligence start-ups that rely on these mechanisms?

According to Jerry Ye, founder and CEO of Whale, a China-based digital marketing start-up, the crux of the issue is what data are fed into algorithms, not the algorithms themselves. Companies with solutions based on highly sensitive facial or other biological data will inevitably be severely impacted.

A Beijing-based investor with exposure to start-ups developing facial recognition software confirms that fundraising across the industry has halted amid the uncertainty. Operations, however, continue. Jiawei Wu, a lawyer at Zhong Lun Law Firm, adds that understanding the proposal is contingent on studying two further laws on data.

First, the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which came into effect on November 1. It states that automated decision-making should be transparent and fair, and it should not impose unreasonable differential treatment on individuals in terms of transaction prices. This is aimed at e-commerce platforms, which leverage algorithms to market products to frequently returning customers at higher prices than those for newcomers.

In addition, individuals should be able to conveniently refuse AI-based commercial marketing. They could ask those responsible for data processing to explain the decision-making process, and ultimately refuse or opt-out of targeted advertising based on personal characteristics. This is primarily a data security issue.

Second, the Data Security Law (DSL), which came into effect on September 1. There is a focus on establishing data that are sourced legally, and it falls on investments and management teams to lead verification, says Wu. Key considerations include whether the data provider is properly licensed, and whether disclosure would constitute a breach of contract.

While biometric data are subject to strict controls, there are legal grounds for use, such as when there are national security implications, or it helps address anti-money laundering and risk controls in financial institutions.

Algorithms are regulated simply because their misuse – deliberately or otherwise – can have serious consequences. Google and Facebook's AI engines have both mistakenly identified black people are primates, while Detroit police arrested the wrong man for shoplifting after facial recognition software picked him on security camera footage.

"Currently, details of the rules are not clear. Investors should wait and see how standards are enforced," Wu adds.

Industry participants are also watching developments in the automotive industry – where AI is employed in road mapping and data, autonomous driving, and smart cabin controls – with interest. The industry is already subject to tight supervision, so might serve as a reference point for others.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.