China e-commerce: Chaos in the community

With investor sentiment on China’s technology sector cooling, community group buying platforms are battling to conserve cash. This has done little for the government’s anti-monopoly drive

Pengyu He, founder and CEO of Tongcheng Life, once China's leading community group buying operator, made his last address to employees in early July, standing between two policemen in the Suzhou Arbitration Bureau. The crowd was impatient because Toncheng Life had just gone bust.

"For those who are willing to start a new business with me, I can offer you a 20% share for free. That's all I can do now. I'm sorry, brothers. I am really sorry," He said, speaking over continued interruptions from employees wanting answers. Within minutes, he was pulled away by the police.

Tongcheng Life is the largest bankruptcy in China's community group buying space. Incubated by online travel agency Tongcheng-Elong in 2018, the company raised more than $300 million from the likes of Legend Capital, BAI, Welight Capital, GSR Ventures, and Oriza Holdings. It achieved a valuation of $1 billion in 2020. Tongcheng Life ended up with debts of RMB1.3 billion ($203 million).

There have been other failures. Wuhan-based Shixianghui and Hefei-based Dailuobo, which were backed by investors such as Hillhouse Capital and Softbank Ventures Asia, also ceased operations this year. It comes in sharp contrast to 2020 when capital poured into the space, enabling ever-larger rounds at ever-higher valuations.

"The COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020 led to sharp growth in community group buying revenue – people simply didn't have other choices when stores and wet markets were closed. But growth slowed after the pandemic came under control," says Charlie Chen, director of China Renaissance Securities, "Community group buying businesses are still loss-making, and they can't continue burning cash with no new capital input."

Community group buying players rely on designated individuals – referred to as team heads – who coordinate activity in their neighborhoods. This involves gauging and aggregating demand, placing orders, and arranging bulk delivery. They receive a fee for their work, typically a share of the profit. Consumers collect items themselves from local pick-up points.

Tightening the screw

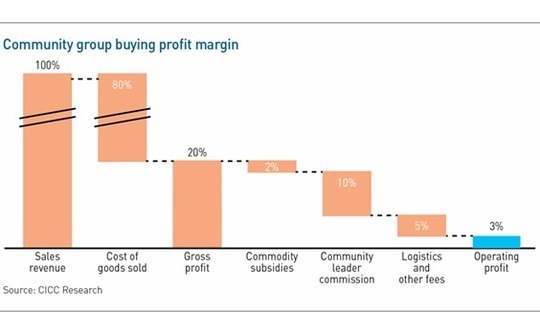

The industry is worth up to RMB1.5 trillion ($235 billion), according to China International Capital Corporation (CICC). It expects a larger portion of this revenue to go to a smaller number of participants, as consolidation reduces the competition to three or four giants.

However, this outcome appears to be something regulators would rather avoid. In December 2020, several months after the likes of Pinduoduo, Meituan, and Didi expanded into community group buying, People's Daily declared: "People expect them [internet giants] to take on more responsibility in promoting technological innovation. They shouldn't just care about the internet traffic flow regarding a few bundles of cabbage and a few kilograms of fruit."

Regulators responded by getting tough. In March, RMB1.5 million in fines were issued to Meituan, Nice Tuan, Pinduoduo and Didi-owned Chengxin Youxuan for "dumping products at prices below cost." Snap inspections began, with platforms ordered to take restorative action when they were caught selling certain products at a negative gross margin.

At the end of May, Nice Tuan was fined another RMB1.5 million and forced to suspend business operations for three days. Other platforms were called in for interview and told bluntly, "Follow the rules or we'll close you down," one executive with a community group-buying company tells AVCJ. Penny flash sales disappeared overnight.

Intervention has long-term benefits. It helps shift the commercial emphasis from high-cash-burn for customer acquisition to supply chain management, cost controls, and customer retention. But for many investors, there was relief that portfolio companies were less likely to get crushed by the mega-platforms.

"The biggest concern for a start-up is often coming into direct competition with the internet giants. When we backed ride-hailing businesses, we were really frightened when we heard that Meituan or Tencent was going to launch a business of its own," an investor explains.

Nice Tuan closed its Series D round at $750 million in March, three months after raising $196 million for the fourth tranche of its Series C. In May, it launched a new round, seeking $1 billion at a valuation of $5 billion, according to the investor, who has exposure to the company. Despite the recent suspension, Nice Tuan was emboldened by the ban on subsidies, reasoning that it would benefit from a more stable competitive environment.

Then consumer-facing internet companies had their world turned upside down. Two days after its US IPO, Didi was placed under investigation – and barred from registering new users – for violating data privacy rules. With investors suddenly gun-shy, unsure where and when regulators would strike next, start-ups realized that fundraising would be difficult.

Chengxin Youxuan was the first to retreat. At the end of July, its Chengdu headquarters was closed and 30% of its staff were laid off, local media reported. In August, the "war subsidy" – a bonus amounting to 20% of an employee's monthly salary, intended to encourage them to fight for market share – was abolished. As of September, the company's coverage has been cut from 31 to nine provinces.

Nice Tuan was advised to pull back from cities where it wasn't well established and focus on core markets, says the same investor. This has impacted 90% of its coverage area. The target valuation for the new funding round was lowered, but some existing investors still passed. Nice Tuan ended up raising less than half the expected sum.

"Some investors in the space are pre-IPO investors. Previously, they weren't looking for sustainable business models, they just wanted to exit after the IPO. When the data privacy law created uncertainty over US IPOs, these investors thought twice about recommitting," an industry analyst explains.

Still dominant

China Merchants Securities estimates the community group buying industry will incur losses of more than RMB20 billion this year. Meanwhile, the path to exit remains unclear. This is bad news for private equity investors, but the internet giants might look at the situation differently.

Community group buying is a prime source of offline consumer data, direct from communities. At a time when costs tied to promotions and accessing online traffic are extremely high, offline traffic is of great value. Even though these businesses are loss-making, the parent can still benefit by leveraging data to support profitable endeavors.

Chengxin Youxuan is arguably the most disadvantaged of the larger players because Didi has no e-commerce platform through which to realize synergies. "Its unit economics are the worst among the internet giant-backed platforms. Community group buying requires supply chain construction, but compared to Pinduoduo or Meituan, Chengxin Youxuan has no retail genes and little experience in e-commerce distribution," says a second investor.

In early June, the company began negotiations with JD.com and ByteDance over a potential sale, but they soon walked away. Taicaicai, an Alibaba Group-owned community group buying business formed through the merger of Hema Jishi and Taobao Grocery, has taken over many of Chengxin Youxuan's suppliers and franchisees. It now ranks third in the market after Pinduoduo and Meituan.

Despite attempts to level the playing field, it appears that internet giants remain a dominant force. In addition to the top three, Xingsheng Youxuan is heavily backed by Tencent and JD.com, Nice Tuan is aligned with Alibaba, and JD.com has its own Jingxi Pinpin brand.

Asked if they would consider backing another start-up in community group buying, investors are quick to respond in the negative. Regulatory intervention has reined in major players across China's technology sector, not least through direct investigations into anti-monopolistic behavior. But the liquidity squeeze means is asking tough questions about business model sustainability.

"From this perspective, you could say that supervision may have shortened these start-ups' survival time because of a slowdown in investment. From another perspective, regulation is actually helping small companies enjoy a level playing field," says China Renaissance's Chen.

"The problem is that before small companies can fully enjoy the benefits of antitrust, the investors behind them may have already withdrawn."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.