Japan fundraising: Regional banks revisited

Japan’s regional banks have risen from a low base to become a meaningful LP constituency for local middle-market managers. Their staying power might be a function of broader industry consolidation

Shinsei Bank broke new ground in 2000 when the lender – then known as Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan – was acquired out of bankruptcy by Ripplewood Holdings and JC Flowers. Foreign investors had never previously secured control of a Japanese bank, and it led to a remarkable, and lucrative, turnaround that impacted the broader financial services sector.

More than two decades on, it's possible Shinsei will once again play a pioneering role in Japan M&A as part of a new wave of hostile takeovers in Japan. Last month, SBI Holdings offered JPY116.4 billion ($1.1 billion) to increase its holding from 20% to 48%, pushing the bank's board on the defensive. Private equity is not an actor in this drama, yet it might become an indirect beneficiary.

SBI, a holding company with a diverse range of interests across financial services, has outlined grand ambitions to create Japan's fourth megabank. Shinsei may form part of the puzzle. But SBI is already busy buying up stakes in Japan's regional banks, taking the lead in a national consolidation drive.

Negative interest rates have made life difficult for these lenders as they accumulate deposits yet struggle to extend loans. This dilemma has prompted many to make commitments to private equity funds rather than hold assets on their balance sheets. Consolidation could result in the emergence of a handful of larger players better equipped and resourced to participate in the asset class.

"There is a lot of pressure on tier-two regional banks to consolidate," says Hiroshi Nonomiya, CEO of local placement agent Crosspoint Advisors. "This trend will continue, and it is good news for private equity. If the regional banks consolidate, they will have the capability to do sophisticated private equity investment. Right now, smaller banks can only do alternative investment on a limited scale."

Burst of activity

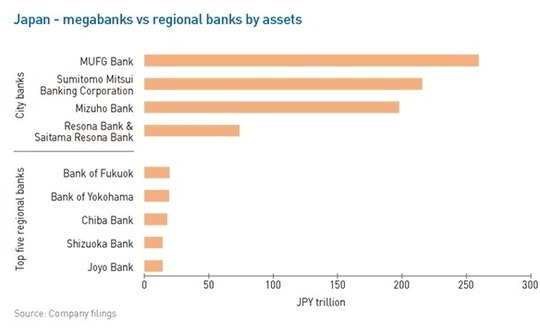

There are currently 99 regional banks in Japan, 62 in the first tier and 37 in the second. The top tier has changed little in the past 20 years, while the number of second-tier members has shrunk by more than one-third. First-tier lenders held JPY394 trillion in assets as of March (five city banks, including the three megabanks, had nearly twice as much), led by a handful of large players.

The 10 largest regional banks account for approximately one-third of tier-one assets, with Bank of Fukuoka, Bank of Yokohama, Chiba Bank, Shizuoka Bank, and Joyo Bank making up the top five.

It was in the 2016-2017 vintage of domestic funds, which launched in the months following the introduction of negative interest rates, that regional bank participation became noticeably more visible. Ten middle-market buyout managers achieved final closes in 2017 – six were announced in the month of April alone – with local LPs accounting for the bulk of commitments in most cases.

Notably, megabanks and insurers were willing to commit larger sums than before, and regional banks followed suit, albeit with smaller checks. Almost every GP noted an uptick. Tokio Marine Capital closed its fifth fund with JPY51.7 billion from 34 LPs, all of them domestic, compared to JPY23.3 billion from 18 in the previous vintage. One-third of the Fund V corpus came from 17 regional banks.

Tokio Marine went fully independent and rebranded as T Capital Partners before raising JPY81 billion for its sixth fund earlier this year. While foreign investors were tapped for the first time, there were still over 40 local LPs. However, the number of regional banks fell below a dozen. The likes of CLSA Capital Partners and Aspirant also saw a drop in regional bank participation on the previous vintage.

"The major players that have some experience committing to private equity are still there," says Koji Sasaki, a managing partner at T Capital. "But 2016 was a boom period for regional banks and we saw a lot of newcomers with no experience making LP commitments. Some of them decided to withdraw, perhaps because their expectations were much higher than they should have been."

Competing priorities

The macroeconomic case for stepping back is weak. Until interest rates turn positive, regional banks will effectively be paying Bank of Japan (BoJ) for every yen they retain on their balance sheets. Meanwhile, domestic private equity has performed well.

"The market is growing, there are more deals, and the returns have been great – 2x is fantastic by domestic standards," one international placement agent who covers the Japan market observes. "If you only need to generate 5% net and you are getting 15-20% net, why would you not continue to invest unless there is a liquidity crunch? And the problem in Japan is too much liquidity."

A couple of regional banks were prevented from re-upping in T Capital because of policy changes that required them to prioritize investments or other financing solutions in their localities over commitments to Tokyo-based GPs. As for the expectations factor, financial returns are only one consideration: banks also want to establish relationships and secure leveraged financing work.

If these downstream opportunities haven't materialized, a re-up may not be forthcoming, notes Niklas Amundsson, a partner at Monument Group. Equally, the relationship might be established and fruitful, but the regional bank sees the new fund is oversubscribed, so there's no pressing need for its capital and it looks for other ways to be helpful.

Another explanation is fees. According to Taketo Furuya, founder and CEO of Ark Totan Alternative, another local placement agent, management fees paid to GPs are often categorized with brokerage fees, on opposing sides of the ledger. How much of what is made on mutual fund sales is wiped out by PE exposure and is it counterbalanced by additional leveraged financing mandates?

"If they are paying 2% on a $20 million investment, that's $400,000 in management fees every year. Board members are pushing back, saying ‘We need to revisit this fee issue because we are spending a lot of time and resources on mutual funds and making money there, and then paying it out again with one private equity fund investment.' Some banks have stopped investing," he explains.

This perspective highlights the distinction between relative newcomers to private equity and those seasoned enough to have seen beyond the j-curve and recognize the long-term appeal of the asset class. There tends to be a positive correlation between asset size and length of exposure to private equity and the quantum of internal resources devoted to it.

Relationship, strategic, financial

Kazushige Kobayashi, a managing director at MCP Asset Management who oversees a local fund-of-funds program, places regional banks into three categories – relationship-driven, strategic-driven, and financial-driven. The first group usually assign PE coverage to the general investment team, while the second group lumps it with business development because they prioritize synergies.

Financial-driven investors are more likely to have dedicated private equity teams. Bank of Fukuoka and Shizuoka Bank – both members of the top five regional lenders by assets – are said to fit this profile. "I still remember meeting a guy from Shizuoka Bank who had private equity on his business card," Furuya recalls. "I'd never come across anyone else like that from a regional bank."

In certain cases, an external private equity program is a natural extension of an internal principal investment business intended to help local corporates facing succession or turnaround challenges. Chiba Bank Capital and Hiroshima Bank's Hirogin Capital Partners are cited as examples.

There are also situations in which regional banks team up to boost their firepower. Shikoku Alliance Capital was established in 2018 by Awa Bank, Hyakujushi Bank, Iyo Bank, and Shikoku Bank to invest in Shikoku, the smallest of Japan's major islands. However, it is unclear where the socioeconomic mandate stops and the financial mandate begins, which can have implications for recruitment.

"Captive private equity funds often aren't managed well because anyone from a regional bank could be seconded to manage them as opposed to professional investors. And they don't raise capital from institutional investors," says Crosspoint's Nonomiya. "But we have seen banks team up with local private equity firms that do know how to manage funds."

RBG Partners might represent the next evolution in that thinking. An independent manager set up in 2018 by a team from Sumitomo Mitsubishi Banking Corporation (SMBC), a debut fund of JPY4 billion was raised from Yokohama Bank, Hokuriku Bank, and Japan Post Bank. Yokohama Bank also took a minority stake in the GP, suggesting it sees private equity as a long-term strategic priority.

RBG is now looking to raise a second vehicle of $150-200 million from a broader institutional investor base, according to a source close to the situation. The firm remains headquartered in Yokohama and its name derives from Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse, a Meiji era customs building turned culture and retail venue that is one of the city's most iconic landmarks.

Regional banks tend to write equity checks of $10-30 million for domestic private equity funds, but T Capital's Sasaki notes that the larger players can commit $50 million-plus, approaching megabank territory. It's possible that industry consolidation will lead to larger checks and more strategic initiatives along the lines of RBG and Yokohama Bank.

These lenders might also become more comfortable allocating to overseas private equity funds. A few are said to have done this on their own or under the close guidance of gatekeepers. Asset managers such as Development Bank of Japan (DBJ) have also established structures to aggregate commitments and deploy the capital internationally.

Secondaries to come?

SBI said last year that it would invest in up to 10 regional banks as part of its fourth megabank agenda, and it has ties to around 40 others through a regional revitalization joint venture. Meanwhile, the Financial Services Agency (FSA) and BoJ are encouraging consolidation. BoJ has offered subsidies in the form of preferential interest rates to lenders that move in this direction.

It all points to a bifurcated universe in which a handful of large players increase their competencies and capabilities and the rest fall back. Industry participants see a nascent secondary opportunity as some regional banks retrench and pare their private equity exposure. However, this will take years to play out. Groups that have ceased new commitments aren't necessarily selling existing positions.

Bee Alternatives, formed following a spinout by Ant Capital Partners' secondaries team, expects to invest no more than 40% of its debut fund in Japan. But there is a regional bank angle, specifically helping lenders generate the capital for re-ups in new funds – so they can retain relationships with GPs – by facilitating partial exits from earlier vintages, according to a source familiar with the firm.

The challenge is largely educational and procedural, and confined to the less sophisticated groups. Some banks are not only unaware of secondaries and how they work, but they also lack the systems to monitor fund performance, the source adds. Assets might be held at cost, and no one knows how to assess whether a theoretical secondary transaction represents fair value.

Moriyoshi Matsumoto, a managing partner at WM Partners, another local secondary investor, alludes to the same problem. WM recently launched a fund with Alternative Investment Capital that will target LP positions in domestic funds. Larger banks, life insurance companies, and corporates are expected to be the primary source of deal flow.

Matsumoto admits that the regional bank opportunity "is warming up" but sellers will require a lot of support from the likes of SMBC and DBJ – WM's strategic partners – because they "do not know how to sell and how to evaluate the funds they hold now."

"One of the difficulties in Japan is that investors don't like to jump into transactions if they haven't found any cases before," he explains. "At the same time, they don't like making decisions themselves – so they need advice to move forward – and they don't have much idea about the market or process of the transaction."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.