Vision Fund: Big is beautiful?

Previously the sole elephant in Asia’s growth-stage technology space, SoftBank’s Vision Fund program is now one of a herd. Prevailing amid increased competition may prove its thesis once and for all

Inside SoftBank Group, the Vision Funds represent a transition from telecoms-focused conglomerate to semi-corporate venture capital investor, at least in terms of cash flow. Outside the company, their significance is far greater.

With corpuses that dwarf anything else in the global VC space, the Vision Funds are known for placing outsized bets on perceived market leaders and have subsequently become something of a highwire act: spectacular when all goes well but disastrous when it doesn’t. In some ways, this is in keeping with the traditional venture risk equation, only with higher stakes. In other ways, it changes everything.

“Organizations that receive these big bets have a tremendous advantage and gain the resources they need to further accelerate their development and widen the gap between them and their competitors. This leads to even further investment and the cycle continues. In effect, market leaders of the future are chosen early in their evolution and then investors pile on, one after another. Winners become big winners,” says Jonathan Lavender, KPMG’s global head of private enterprise.

“The Vision Fund has forced other VCs to raise bigger funds themselves or risk being left out of the best deals. Market leaders are commanding big raises – and they are also getting high valuations – as investors compete to fund them. For those companies that Vision – or other large VC funds – consider to be winners, there seems to be an endless number of rounds available.”

Vision Fund 1 (SVF1) closed at $98.6 billion in 2018 with almost half the capital coming from Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, 28% from SoftBank, and the rest from the likes of Apple, Qualcomm, Sharp, and Foxconn. As of June, $86.2 billion had been deployed – almost half of it in Asia – across 92 deals. Realizations totaled $34.6 billion, while write-downs amounted to $17.3 billion

Controversy around the write-downs impacted Vision Fund 2 (SVF2) in 2019. With many LPs hesitant to commit, SoftBank provided the entire $40 million corpus, shifting to mostly smaller, earlier-stage investments, albeit with an unapologetic stride that suggests ongoing confidence in the big-check concept. The fund is already 50% deployed across more than 90 companies.

WeWork and Coupang

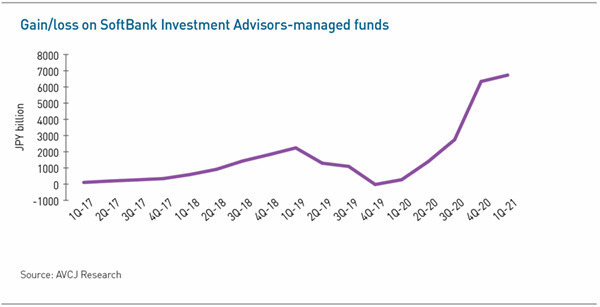

Industry sentiment on the Vision Fund experiment can largely be tracked in the performance of two investments: US co-working space player WeWork and Korean e-commerce giant Coupang. SVF1 committed $3 billion to WeWork at a valuation of $43 million before an overextended expansion agenda saw the company implode ahead of a planned IPO in 2019. It contributed $3.3 billion to SVF1’s losses and reinforced criticism about the wisdom of trying to create winners through sheer financial firepower.

Coupang, meanwhile, became the lead example of Vision’s reputational and financial comeback as a huge expansion drive culminated in a $4.5 billion US IPO in March; it currently has a market capitalization $46 billion. SoftBank invested $3 billion in the company from balance sheet between 2015 and 2018 before transferring the asset to SVF1, which is sitting on an unrealized gain of $24 billion.

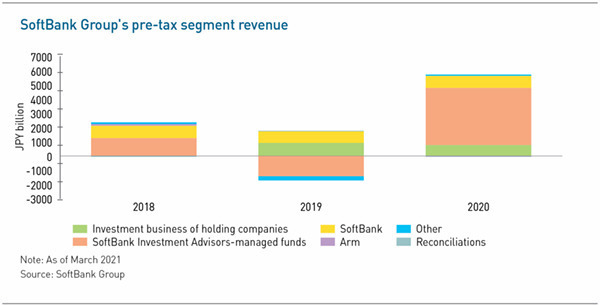

SoftBank’s balance sheet undulations in the past three years illustrate the rebound best. The unit that manages the Vision Funds, SoftBank Investment Advisors, recorded pre-tax revenue of JPY1.2 trillion ($11.1 billion) in 2018, negative JPY1.4 trillion in 2019, and JPY4 trillion in 2020.

Throughout the rollercoaster, confidence and skepticism about the strategy has been distilled in SoftBank’s enigmatic founder Masayoshi Son, universally known as Masa. Son’s early bets on Alibaba Group and Yahoo Japan cemented his reputation as a tech clairvoyant, while his passionate, Star Wars-quoting rapport with entrepreneurs has established him as a start-up whisperer.

None of these emotional inputs have changed with the downsizing of SVF2 and the industry-wide rise of mega rounds for minority stakes. To some extent, the Masa factor hints that SoftBank, other large-cap investors, and entrepreneurs continue to believe in the Vision Fund way. But there is also a sense that the big-money genie has been let out of the bottle, and there is no turning back from competitive, super-sized VC.

“Masa thought that SoftBank’s capital would be a differentiator and for a relatively short period of time, it was. Now it’s not at all,” says Gary Rieschel, who met Son in the 1980s and helped set up SoftBank’s early VC funds in the US and Asia before establishing Qiming Venture Partners in 2005.

“The biggest difference between SoftBank 20 years ago and now is back then Masa seeing things before the entire world could see them. Now, Vision Fund is seeing things at the same time as a lot of other people and fighting to deploy capital against them. And there is no such thing as cornering market share given the amount of money washing around the planet.”

Competitive threats

The emergence of sustained multi-hundred-million-dollar growth rounds for technology companies in recent years appears to be a validation of Vision Fund among sovereigns, corporates, public-private crossover investors, and global VCs. According to AVCJ Research, the amount of capital invested in $100 million-plus rounds increased 60% in China between 2019 and 2020. That figure was 57% in India and 43% in Southeast Asia.

Valuations have boomed, especially in potentially winner-take-all categories where the “money moat” approach of creating a runaway leader is seen as more credible. For example, even with its relatively subdued mandate, SVF2 provided an entire $1.7 billion round for Korean travel services player Yanolja in July, valuing the company at around $9 billion.

There is more to the trend than following Vision Fund’s lead, however, not least of which is the logic that most of the returns for any given company come before its IPO.

Among sovereigns and corporates, there are strategic agendas. For those crossing over from public markets, going pre-IPO can boil down to a lack of patience. For global financial VCs such as Insight Partners, the decision to relax on valuations is often driven by high conviction in other areas such as customer validation, team quality, or technology differentiation.

“Entrepreneurs have a lot more choices from different types of firms, and we as investors must work harder to ensure that when we are excited about a company, we earn the entrepreneur’s trust. The ball is definitely in the founders’ court,” says Praveen Akkiraju, a managing director at Insight, who previously led the enterprise and software-as-a-service practice for SVF1.

“In an environment where there’s a lot of capital and it’s being deployed very fast, there will always be anomalies in terms of how fundings are done and what types of companies are funded. But you have to look at this as a multi-sided event. It’s not just the capital – it’s also the fact that we are getting more innovation. Whether it’s individual consumers or corporations, they’re more willing to try new things.”

It's an open question as to whether all this is good for VC. Meanwhile, the early concentration of funding on perceived winners limits competition, which may not benefit end-customers in the long run.

There is also the idea that early-stage companies are encouraged to demonstrate their capacity to be market leaders of the future by eschewing a more traditional approach to growth where they focus on profitability as they go and instead prioritizing revenue and market share expansion. They can become so used to growing top line that it is hard to shift toward profitability, leaving investors disappointed.

“Valuations have skyrocketed in Southeast Asia on the growth side, with many unicorns propped up by sovereign wealth funds, corporates, and the likes of Vision Fund. That is in many ways a reflection of the long-dated view of those investors. In markets like this, where long-term growth and development is yet to be experienced, they can take advantage of some arbitrage,” says Alex Boulton, a partner at Bain & Company.

“The question is, will valuations continue to go up? We are starting to see down rounds and that can be quite challenging for the previous investors.”

Too much, too soon

Pumping cash into relatively young companies can have subtler, founder-level effects as well. The introduction of big money too early in a company lifecycle clashes with the school of thought that leaner businesses are more efficient. It consequently sets up pitfalls around wastage of funds on initiatives that don’t necessarily generate the best return and other poor strategic decision-making.

In some cases, big funding rounds can be misaligned with the scaling realities of the target industry. Company growth in telemedicine, for example, is dependent on the availability of doctors on a 24-hour basis, a business quotient that can be addressed with capital only to a point. Overextension in these scenarios is essentially a matter of burning cash to create a poor customer experience.

“Imagine you are a start-up, and you are running a marathon for five years and you’ve finally got over the hill, you see the finish line where you IPO, and someone gives you this energy drink. There are only a few cans on the table, so you want to grab it if it’s available. Could the energy drink leave you with a hangover or dehydration? I suppose so,” says Khailee Ng, a managing partner at 500 Global.

“When a company gets too much money too soon, if its existing business model has preexisting conditions, those would be exacerbated.”

At the transaction level, more pain could come with a proliferation of a relatively low-diligence investing style and increasingly complex term sheets. Oftentimes, the larger the round, the fiercer the negotiating battle over the small print. On one hand, sizeable investors request preferential treatment in corporate governance rights and follow-on rounds. On the other, companies attempt to streamline their obligations and rights packages with those of other investors.

“Some companies do not want a single investor holding so much power, as some companies want to maintain their flexibility and leverage by dealing with a dispersed investor base,” says Douglas Freeman, a partner at Goodwin Procter.

Vision Fund may have an edge in this area given the cult of personality that exists around Son. When larger asset managers play in growth-stage tech rounds, entrepreneurs are instinctively wary and less persuaded by the slick deal teams involved, which often have culturally alien backgrounds in banking. Although Vision Fund’s top people also fit this mold, the boss himself has proven an ace up their sleeve.

“I’ve had entrepreneurs come back to me and say, ‘Masa called last night, he wants to put in an extra $50 million.’ I say, ‘Okay, but didn’t we say we would keep the round to this size?’ And they are like, ‘But Masa says this,’” says one investor. “The star power still works, maybe not as much as three years ago, but every entrepreneur is going to take that call.”

Beyond China

There is also a significant geographic lens to the Vision Fund effect, which has seen much of the industry take a wait-and-see approach to China as regulatory action in the local technology sector plays out. This has accelerated a diversification drive into India and Southeast Asia has been unfolding among global players for several years. In the third quarter of 2021, India growth-oriented technology investment outstripped China for the first time since 2009.

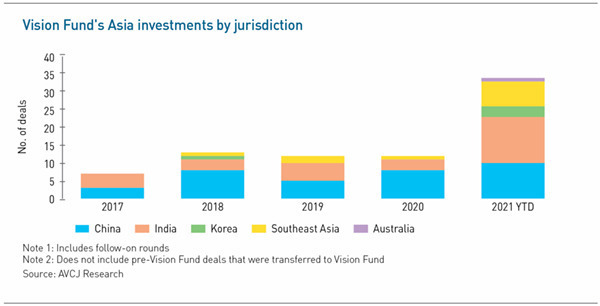

SoftBank has been hit by this wave to no small degree, given its 25% stake in Alibaba, one of multiple platform internet companies investigated for antitrust violations. It was announced in August that the Vision Funds’ exposure to China would fall from one-third to 23%. SVF2 already has more invested in Asia ex-China than in China. With the momentum of Coupang, Korea has been mooted as a potential beneficiary of the ongoing reallocation, but India and Southeast Asia remain the biggest targets.

Between 2018 and 2020, Vision Fund averaged a dozen deals a year in Asia and China accounted for more than half. SVF2 activity in 2021 is characterized by smaller checks for more companies across a wider selection of geographies. Of the 34 funding rounds announced as early October, China, India, and Southeast Asia accounted for 10, 13, and seven, respectively.

“In the last six months in Southeast Asia, so many people have come out of the woodwork, especially US investors looking for mid-stage and late-stage technology companies,” says Shane Chesson, co-founder of Singapore-based Openspace Ventures.

“I know of situations where someone has jumped in and got exclusivity, so other large investors couldn’t make aggressive bids like they normally would. Do those other investors feel they’re getting enough of what they want? Are they going to go earlier or increase the pressure on price? Both things could happen.”

In addition to the long-term nature of the opportunity, the argument for large-cap investors coming to ASEAN is increasingly supported by better visibility on exits. Consumer internet platform Sea paved much of the path with its US listing in 2017, while further encouragement came in August when Buklapak, an Indonesian e-commerce company, raised $1.5 billion in a domestic IPO.

A similar theme is playing out in India, where a greater understanding of tech business models among a large existing retail investor base is helping fuel an IPO boom and a corresponding swell in late-stage VC investment. Among the more recent beneficiaries of the trend is education platform Unacademy, which closed a $440 million round in August at a valuation of $3.4 billion with support from SVF2, Tiger Global Management, and General Atlantic.

Blume Ventures, Unacademy’s first institutional backer, expects this kind of activity to amplify its opportunity to realize investments via secondary sales – although it did not exit in the latest round, citing continued upside for the edtech company. Kunal Bajaj, Blume’s head of growth and exits, notes that the influx of heavyweight investors could also bring real value to companies like Unacademy.

“Having these crossover investors on your cap table 2-3 years ahead of your IPO allows you to start bringing discipline into your reporting, forward planning, investor communications, and strategy. It allows you to get a sense of the kinds of metrics the public market values, which could be very different from private markets,” he says. “A lot of the value these investors bring to the table is to cross that gap and say, ‘This is what you need to focus on because this is what the public markets value.’”

Value proposition

The Vision Funds could offer this and more by drawing on their parent’s resources. In addition to Alibaba and Yahoo, the SoftBank ecosystem encompasses Sprint, Line, T-Mobile, NEC, and Vodaphone, implying portfolio synergies for tech companies that would be difficult for other institutions to match.

For example, Automation Anywhere, US robotics software player that SVF1 backed under the guidance of Akkiraju in 2018, instantly went from no Japan presence to a local team of 300 with access to an existing mobile customer base of 35 million. Son calls the value-add strategy “gun-senryaku,” a Japanese term for the way birds fly together.

“I had an online conversation with Masayoshi Son for about 40 minutes and was inspired by his passion. He was very insightful and quickly caught the most important opportunities, which he suggested we focus on,” says Chunquan Ma, CEO of Chinese enterprise fintech company Ekuaibao, which raised a RMB1 billion ($155 million) round in August led by SVF2, which made its decision in less than two months.

“Vision Fund’s post-investment team helped us build financial analysis models, and we had several meetings in just two months. The team had 5-6 people follow up with us, and they introduced us to their other portfolio companies. When the time comes, they will be able to help us expand overseas.”

For Vision Fund, this concept extends to deal sourcing via sister investment units such as early-stage outfit Softbank Ventures Asia (SBVA). In the most recent example, SVF2 led a $400 million round for China-owned and Nigeria-focused logistics start-up Opay at a valuation of $2 billion. This represents the first Vision Fund investment in Africa. SBVA participated in Opay’s Series B in 2019.

“There’s no systematic referral process, but we try to make introductions to rising portfolio companies. Even if it’s not one of our portfolio companies, if it’s a good company that’s too big or late-stage for us, we can bridge them to our colleagues in Vision Fund,” says J.P. Lee, CEO of SBVA.

“In the case of Opay, they’re now able to get more help throughout the SoftBank Vision Fund global network and SoftBank Group’s network. That’s pretty meaningful, so we’re happy to help our companies raise their next round from our family.”

Activity in this vein has helped ease some of the reputational issues the Vision Funds have contended with since the beginning. It also illuminates some of the positive aspects of the money moat thesis related to ecosystem building, secondary market creation, and clarification of timetables to IPO.

Justin Tang, head of Asia research at investment advisory United First Partners, believes that recently improved sentiment for SoftBank can be largely attributed to strategic pivots for Vision Fund at the behest of activist investor Elliot Management, as well as Son playing a steady hand.

“If things work out for Vision Fund 2, I’m sure they could scale up pretty quickly for Fund III or Fund IV. I think right now, it’s about gaining back the confidence of investors and showing them that this is not a cowboy approach,” Tang.

“SoftBank was like an F1 car with only one speed, but they managed to install a few more gears. Now they realize, they can cruise in second gear, and if the opportunity is there, they can put the pedal to the metal. Barring a disaster like WeWork, they should be fine.”

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.