China biotech: Going global

A gradual shift in focus from sourcing assets from overseas for application in China to bringing China-made treatments to the world is challenging the notion of what constitutes a local biotech start-up

WuXi Biologics, China's leading provider of outsourced drug development services, doesn't want to be constrained by borders. The company has seen a gradual international-to-domestic shift in its customer base as local development activity has picked up, notably in biotech.

At the same time, WuXi is pushing a "global dual sourcing" agenda, aimed at meeting the needs of customers across China, the US, and the EU, so that risks associated with cross-company and cross-border technology transfer are minimized. It currently has more than 300,000 liters in annual manufacturing capacity, of which nearly one-third is located outside of China.

There is a clear strategic objective to occupy more of the industry value chain, but WuXi's approach is also representative of China's increasingly significant role in the global drug development ecosystem. Once wholly or primarily focused on in-licensing intellectual property (IP) for application in China, local biotech players want to create their own treatments for patients worldwide.

"Historically, CROs [contract research organizations] and CDMOs [contract development and manufacturing organizations] were the powerhouses for doing clinical trials in China, for local or global sponsors," observes Vikram Kapur, head of Bain & Company's Asia Pacific healthcare practice.

"Now they are saying, ‘I have Chinese biotech companies that want to conduct trials in Australia or North America. How do I provide services to them, so they don't end up with a global CRO?'"

Beyond borders

Just as CROs follow clinical trial locations, investors follow talent. There are various reasons why a biotech start-up might be relevant to China: a treatment that addresses an unmet local need; relationships that offer market access; or even a China-born, overseas-educated founder. An in-country development team – when the drug is for a global market – isn't necessarily one of them.

"China has a lot of advantages. You can't stop people gravitating here because there is so much talent and infrastructure, and costs are lower than in the US," says James Huang, founder partner of Panacea Venture. "But I source deals globally; I don't care where a start-up is based. If they have great IP and I believe they can build infrastructure in the US and China, I will invest in them."

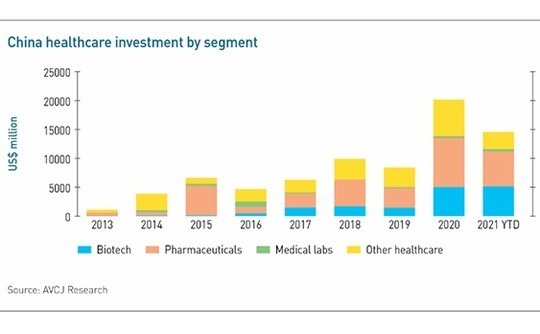

Numerous data points track China's drug development boom. PE and VC investment in healthcare reached a record $20.2 billion in 2020, more than the previous two years combined. Commitments to biotech rose 3.5-fold to $5 billion, while pharmaceuticals more than doubled to $8.5 billion. In 2021 to date, these segments have received $5.1 and $6 billion, respectively.

Huang points to Triarm Therapeutics, a specialist in CAR T-cell therapies that emerged from a research institute in Germany, but now has most of its research headcount in Shanghai and is expanding into the US. The same applies to Nikang Therapeutics. Incubated by CBC Group, it is based in Delaware, has research staff in California and Texas, and is considering an R&D center in China.

"Healthcare is a global business – that's why we have the largest global footprint of any PE healthcare firm in Asia. One-third of our people are outside of China. Being in the US, Japan, and Europe is a huge advantage," says Wei Fu, CEO of CBC. "We are getting talent globally to make drugs; we are sourcing innovations globally; and we are commercializing those innovations globally."

In and out

While incubation is a core part of CBC's business, out-licensing isn't necessarily an immediate goal. I-Mab Biopharma and Everest Medicines were established by the private equity firm to pursue in-licensing strategies, targeting overseas IP where there was a clear line of sight to monetization in the China market. Both listed last year; I-Mab on NASDAQ and Everest in Hong Kong.

Eight months after going public, I-Mab struck its first out-licensing deal with US-based AbbVie. It involves an anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody, which inhibits "don't eat me" signals sent by cancer cells to immune system cells that destroy bacteria and other harmful organisms.

CD47 serves a similar cellular communication disruption function to PD-1, another checkpoint inhibitor-based cancer treatment that has become popular in China. PD-1 prevents cancer cells from binding with a specific protein that renders immune cells unable to detect them. BeiGene, which was previously backed by private equity, announced a PD-1 out-licensing deal with Novartis in January.

It is argued that the turning point for China out-licensing came in 2017 when the country was accepted into the ICH, a global pharmaceutical industry body that creates unified technical standards and guidelines for drug developers. This accelerated the entry of international treatments into the China market, and vice versa, through mechanisms such as mutual recognition of clinical trials data.

The tipping point may have come in 2020. "It was a breakout year, with more nascent innovation and more global partnerships involving best-in-class products," says Marietta Wu, a managing director at Quan Capital, citing I-Mab, BeiGene, and Junshi Biosciences partnering with Eli Lilly on a COVID-19 antibody treatment. "There was a collection of high-quality deals, and it has continued in 2021."

Like Panacea and CBC, Quan Capital invests globally, conducting top-down research into areas it finds interesting and helping to create companies if no existing operator fulfills the criteria. A lot of deals come out of the US and China, given its strong presence in both markets. "Local is an important consideration, but perhaps less important," Wu adds. "Science has no borders."

Discarding geographic silos has implications for operational input as well as deal-sourcing strategy. Investors targeting post-incubation start-ups must consider what they can offer in addition to capital, with recruitment, technical input, and commercialization among the key issues. This would include deciding when to out-license and who to consider as partners.

"What are the investor's relationships like in the big biotech clusters? If a VC has roots in North America or Europe, can it help a start-up commercialize or think through the trial processes in foreign markets, and potentially facilitate an exit in that market?" says Bain's Kapur.

People power

Quan Capital was established by Samantha Du, a one-time healthcare investor at Sequoia Capital who founded Chinese drug developer Zai Lab in 2013. The original thesis was in-licensing, but the company struck its first global co-development deal in 2017 and most projects since then have followed the same format.

Du is not the only investor-turned-entrepreneur in the space. Jonathan Wang co-founded OrbiMed Asia in 2007 and departed two years ago as Inmagene Biopharmaceuticals gained traction. The company started in China but has formed an R&D group out of San Diego. It is working on about 20 drug candidates, some in-licensed and others co-developed with global pharma players.

Panacea's Huang draws comparisons between Wang and Michael Yu, founder of Innovent Biologics, which has in-licensed and commercialized drugs in China and has started out-licensing as well, with offices in Europe and the US. Both individuals are comfortable operating across global markets.

"Michael has the skill set of a Chinese scientist who has worked as an executive for a US biotech company," Huang observes. "These cross-border businesses are being built and run by returnees. They have been in the industry for a long time in the US and Europe, and they returned to China to build their own companies. Now they are building infrastructure outside of China."

The presence of heavily credentialed founders and experienced teams is often a differentiating factor when developing drugs from scratch. Even as more Chinese biotech players outline grand ambitions, there are still significant gaps between China and its global peers in certain areas.

Nikang is working on small-molecule oncology treatments and has already out-licensed one drug candidate to US-based Erasca and begun phase-one clinical trials. This progress underpinned a recent $200 million Series C round. Industry participants claim that China is generally up to five years behind the developed markets on small-molecule drugs.

In CAR-T cell therapy – which involves extracting immune cells from a patient, modifying them, and then returning them to the host to attack tumors – China is making rapid progress, partly because of regulatory support. But CAR-T is often categorized as a medical technology, not a drug. Yifei Wang, a managing director at GL Capital Group, notes that original, high-quality drug discovery is still rare.

"There are two kinds of out-licensing in China. First, the fast-follower model, which you find in areas like PD-1, where the speed of clinical trials has been fast in China and there are good use cases globally," Wang explains. "Second, there is best-in-class out-licensing. For example, the CAR T-cell candidate Cilta-cel that Legend Biotech out-licensed to Janssen Pharmaceutical was among the first developed in its category and the clinical data was very solid."

Being different

To the extent specialized needs are emerging within China's biotech community, emerging CROs and CDMOs looking to challenge local and global incumbents might be encouraged. Most of the VC funding in this space over the past 12 months has gone to companies looking to differentiate their offering in terms of geography or clinical specialty.

Bain's Kapur highlights the success of TPG Capital-owned Novotech in targeting the China-Australia corridor, which has become popular for early-stage clinical trials. "China originated trials happening abroad are growing at a very healthy clip," he says. "A lot of that is because there is a recognition that there is innovation coming out of this market that can be commercialized in other markets."

Joinn Biologics and Thousand Oaks Biopharmaceuticals both earmarked some of their recent funding for US expansion, while dMed Global raised capital to fund a merger with US-based Clinipace. On the specialty side, Quan Capital joined a $96 million Series A in March for Innoforce Pharmaceuticals, which is working with Thermo Fisher to introduce cell and gene therapy manufacturing capabilities.

"A lot of companies have been established in different areas – focusing on small molecules or big molecules – and some are going overseas," says Colin Yu, head of China life sciences at KPMG. "One reason is a policy environment that encourages innovation. Another is that asset-light is the future trend. With external market pressures like price cuts, big pharma companies want to focus on the most profitable parts of the value chain and outsource the rest."

KPMG identified the latter trend two years ago in a report that mapped out how the pharmaceutical industry might evolve through 2030. It identified three business archetypes: the active portfolio company that constantly reappraises its product mix; the virtual chain orchestrator that focuses on solutions rather than owning assets; and the niche specialist that focuses on a single treatment area.

Big pharma companies are increasingly focused on the front end or the back end: seeking differentiation through first-class research or strong go-to-market, and then outsourcing the manufacturing. The future appears to be asset-light, which could create opportunities for start-ups that absorb this capacity. China, however, isn't quite there yet.

"Asset-light and virtual models are common in the West, but not so much in China because there isn't a well-established industry focused on specialty drugs," says Quan Capital's Wu.

"That's changing rapidly, but for now, local biotech leaders have a window of opportunity to grow fast, and not just from an R&D perspective, but covering the whole value chain from discovery to commercialization with every functional area."

The first wave of Chinese biotech start-ups that listed in Hong Kong two years ago, their flagship treatments ready for national rollout, were aggressively hiring sales and marketing staff. As of year-end 2020, Innovent had 1,300 people in commercialization out of a total headcount of 3,200. It has five products approved for marketing in China.

Structural flaw?

The lingering question is whether it pays to be big. Motivations to expand into out-licensing and create drugs for global markets tend to focus on value creation – but there is a China twist. Companies are not so much being pulled overseas by the promise of substantial paydays as being pushed there by eroded economics in their home market.

"Once a drug is commercialized in China, there can still be challenges in terms of market access. First, you need to get your drug listed in public hospitals and that process is not smooth. Then there is inclusion on the drug reimbursement list, which often results in significant price cuts," says KPMG's Yu.

Several industry participants point to PD-1 as a classic case of what happens when mandated price cuts – the cost of qualification for reimbursement under government-backed insurance plans – collide with commercial price competition. PD-1 won approval in China in 2018, four years after the US, and the likes of Junshi and Innovent leaped on the opportunity. Ultimately, so did everyone else.

Innovent is the first and only company to have a PD-1 inhibitor included in the reimbursement list. This broadened the potential customer base, but regulators insisted on a more than 60% price cut. Meanwhile, new entrants flooded the market, putting downward pressure on prices for drugs outside the reimbursement system.

Last year, Innovent made its international breakthrough with an agreement to out-license the PD-1 product to Eli Lilly. BeiGene followed suit with Novartis. But GL Capital's Wang believes the local industry dynamics that prompted Innovent and BeiGene to look overseas are strangling the potential of other companies to come up with similarly significant discoveries.

"A key negative factor in the long-term development of innovative drugs in China is pricing under the national drug reimbursement program," Wang says. "As an example, PD-1 is 20 times more expensive in the US than in China. This makes it very difficult to support a biotech company at a valuation above $1 billion if the lead asset is only developed for the local market."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.