ESG best practice: From global to granular

The value creation-driven PE playbook on ESG in Asia converts marginal gains into big picture policy wins – provided investors focus on the right areas and the flow of information isn’t stymied

From the pursuit of net zero carbon emissions to ensuring companies are run by teams as diverse as their customer bases, ESG (environment, social, and governance) agendas are often underpinned by sweeping, world-changing objectives. The challenge – for institutional investors that endorse these goals and private equity firms that pledge to deliver on them – is granular implementation.

Persuading the founder-entrepreneur of an emerging Asia-based business that adherence to an ESG policy could boost the bottom line is only half the battle. Capital is usually required to pay for the supporting infrastructure so that initiatives can be applied and tracked properly, generating relevant performance data. This must happen consistently across the portfolio, the information flows upwards, from GP to LP, and then maybe the big picture objective gradually moves within reach.

Two months ago, Temasek Holdings and Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan (OTPP) participated as anchor LPs in the $7 billion first close of Brookfield Asset Management's Global Transition Fund. Both groups have committed to achieving net zero by 2050 or sooner, and the fund – which has a target of $12.5 billion – is mandated to accelerate this journey while generating strong risk-adjusted returns.

Ambitions don't get much larger, and Temasek even roots achievements in economics, putting a dollar value on emissions saved: $42 per ton of carbon dioxide. Yet Purnima Gandhi, a vice president who covers sustainability issue for the Singapore government-controlled investment fund, told the AVCJ Singapore Forum that obtaining data to feed into this internal calculator can be difficult.

"Sometimes we have a minority stake and there is a difference in terms of the amount of data you can get as a majority investor," she says. "It's not easy to get all these data from private companies to measure their direct emissions, and most importantly, their indirect emissions – or scope three – which come through the wider impact of the supply chain. You can ask and they will have a few people figure out the emissions, but it's almost like it's done retrospectively."

A rising priority

The obstacles that must be negotiated on the path from company-level disclosure to LP-level reporting become more noticeable as ESG rises ever higher on investors' priority lists.

It has long been a preoccupation of development finance institutions (DFIs), with Geetali Kumar, East Asia and the Pacific lead for disruptive technologies and VC at the International Finance Corporation (IFC), stating flatly that no GP-LP alignment on ESG means no fund commitment.

However, a wider subset of LPs is now asking similar questions. The focus has moved beyond ensuring an ESG or responsible investing policy is in place to scrutinizing implementation, reporting, and integration into the investment lifecycle. In Australia-based Adamantem Capital's most recent fundraise, some LPs issued ESG due diligence questionnaires before they did anything else.

Meanwhile, at a general corporate level, COVID-19 has prompted rethinking in the C-suite. More than half of respondents in a KPMG CEO survey published towards the end of last year said their personal pandemic experiences – either falling ill or seeing others fall ill – had impacted strategy. In addition, 79% admitted to reevaluating their purpose to better address the needs of stakeholders.

Nearly two-thirds said COVID-19 had led to the societal component of ESG programs being prioritized, even as a similar proportion claimed that success in managing climate-related risks will determine whether they retain their jobs.

"The rise of purpose is real in the value proposition and in the war for talent, and it's increasingly relevant for brand reputation among customers. We are seeing social consciousness movements, like Me Too and Black Lives Matter, increasingly influence business as well," she explains. "All of these things – plus the move towards greater regulation on sustainability issues – are driving change."

As industry participants are at pains to point out, ESG is a journey, and the scope is too broad for investors to focus on every aspect at the same time. Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ), for example, identifies key themes within E, S, and G that matter most to it and then digs into the detail on a deal-by-deal basis.

In governance, the pension plan currently emphasizes cybersecurity and tax; in social and environment, the priorities are diversity and inclusion and carbon emissions. Even then, the goalposts are continually moving. In 2017, CDPQ set a target of a 25% reduction in carbon emissions by 2025; as of June, it had achieved a 37% reduction.

"If we are not going to do anything about it, we could go home with our bonuses [emissions reduction is embedded in variable bonus calculations for staff as well as in investment committee decisions]," says Wai Leng Leong, head of Asia Pacific at CDPQ. "But that's not the point. It's a new field, so it must be a dynamic process. We are reexamining at it as we speak."

The pension plan is also reviewing its approach to energy transition. Rather than focusing on areas such as renewables, it is argued that more capital should go to companies in industries where carbon emissions are very high and financial support is required to drive transition to lower levels. This may have a more significant impact on net emissions.

Choose your battles

Picking areas of ESG to concentrate on applies equally at the other end of the spectrum in terms of company-level implementation. These emerge from an understanding of risk and materiality.

"We lay out performance standards for portfolio companies to IFC levels and to ILO [International Labor Organization] levels. It's about engaging with management pre-investment and ensuring there is an alignment to close those gaps. It's also about weighing in on materiality and what is important for the investment," says Michael Octoman, a senior partner and COO at Navis Capital Partners.

The processes around targeting and subsequent engagement vary considerably. As part of its focus on carbon, Adamantem has an emissions reduction committee below the LP advisory committee (LPAC) for its second fund. Other initiatives include responsible investing-related engagement sessions for CEOs from across the portfolio, which serve as forums for sharing best practice. The importance of diversity and inclusion within enterprises has been among the topics covered.

There is a continual emphasis – more pronounced in Asia's emerging markets, though still relevant when dealing with small to midmarket companies in developed economies – on raising skill levels and providing access to expertise in areas where in-house resources might be lacking.

Partners Group's global impact investment business, which has been rebranded as Blue Earth Capital, has chosen to focus on distribution – of goods such as medication and agricultural supplies – to lower-tier cities in Asia's emerging markets. This may generate a combination of social and environmental impact, the latter through fuel efficiency in transportation.

Impact is not strictly quantitative on the social side, but the firm measures as far as possible. For example, when drilling down into the benefits of boosting distribution of authentic medicines in a specific area, it is important to calculate the penetration of inauthentic medicines and to what extent that can be offset. However, Blue Earth must first ask whether companies have the ability and resources to measure and know which metrics to track.

"As we move up the spectrum to more developed companies, we've seen companies that have maybe failed on ESG due diligence in earlier rounds, and they've come back and said, ‘Now we know what we're doing, this is what we've done, will it work?" explains Shanaz Rauff, an investment leader at Blue Earth.

"It's an interesting dialogue you have with founder-entrepreneurs to differentiate yourself and show that you have this bench strength of human capital experts, of HSE [health, safety, and environment] experts to support the company through this journey of change," he says.

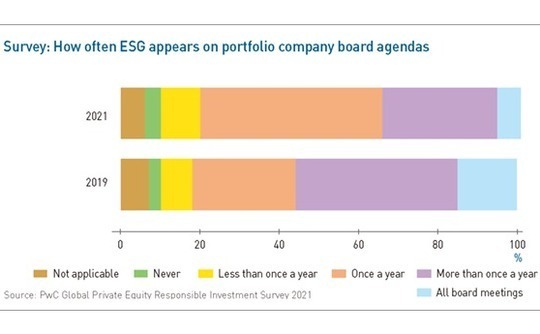

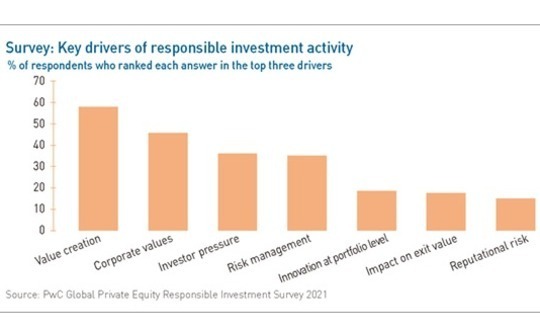

This is essentially where ESG impact and corporate value creation meet, a notion increasingly appreciated by the private equity industry. In PwC's 2019 PE responsible investment survey, risk management was highlighted most frequently as one of the top three drivers of ESG activity. Fast forward to 2021 and risk management falls to fourth, after value creation, corporate values, and investor pressure.

Owners and reporters

Nevertheless, value creation credentials are built on resources and expertise. Navis first considered ESG from a compliance perspective 15 years ago; five years after that, the firm began to look at it through a value creation lens. Over time, a framework emerged that covers the entire investment process, from due diligence and portfolio management through exit. Relatively few private equity firms active in Asia have achieved full integration.

"A lot of companies have ESG checklists – and whether or not they are sufficient is a different issue – but very few have ESG frameworks," says Steven Okun, founder and CEO of APAC Advisors, a consultancy that specializes in ESG, sustainability and stakeholder engagement. "It's not a question of what are the checklists and due diligence, but what are the frameworks to work with companies in the investment phase. That's much harder than doing a checklist and it still needs work [in Asia]."

Establishing what private equity clients want from pre-investment ESG due diligence and helping them achieve it accounts for much of the workload at Blackpeak, an investigative research and advisory firm as well as a sister company of AVCJ. Chris Leahy, a managing director at the firm, notes that investors still struggle with the post-investment part, where there might be tensions between commercial imperatives and social impact.

Obtaining information – which may involve discreet interviews with stakeholders and investigating supply chains – and implementing the right governance protocols is one challenge. Another is establishing which frameworks and reporting standards should be used to process these data.

"The problem with these shrink-wrapped guidelines is they can make people a bit lazy," says Leahy, adding that Blackpeak relies on them as a starting point only. "They are useful as a guideline, but what works for private equity firm A, B or C can be different. You must do what works for the fund rather than have a one-size-fits-all framework imposed by somebody."

A study conducted in May by Duff & Phelps and the International Valuation Standards Council found that nearly half of valuation experts believe a lack of a standardized and recognized measurement system is the biggest threat to effective ESG disclosure. Respondents cited 14 different combinations of frameworks, with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Sustainable Accounting Standards Board (SASB), and Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) among the most popular.

"We need to be more consistent and adopt the same reporting. You have GPs, public companies, private companies – everyone says, ‘I've adopted ESG.' But what have you adopted, how are you measuring it, what reporting matrix are you using? Even if I zoom down to carbon, you could be measuring carbon emissions or carbon intensity, and you could be using data points from different service providers," says CDPQ's Leong.

It is generally hoped that the alphabet soup of reporting standards will be strained into a more unified approach, much like the evolution process for accounting standards where the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and the US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) are preeminent. Some efforts to consolidate ESG frameworks have already begun, with the CFA Institute and the IFRS Institute working on solutions.

Missing the point?

Even if companies reach a point where ESG data capture is fully embedded and it moves seamlessly through consistent assessment mechanisms and into standardized reporting formats, that's not where they should stop. Temasek's Gandhi sees number-crunching and benchmarking as a minimum; thereafter, companies must think beyond the financial risk element in their reporting.

An additional concern, identified by Rauff of Blue Earth, is that IFRS is already to some extent abused in that businesses meet a basic level requirement and then put their own spin on financial results. A common ESG reporting standard might encourage similar behavior, although at the other extreme, anything too detailed or prescriptive risks confusing and alienating less well-resourced players.

"The risk of overreporting and over-compliance is a real one," she says. "Going forward, the key thing will be to manage the burgeoning reporting requirements amidst the need to see what really shifts the needle for any given company or sector."

New regulation is coming thick and fast, from TCFD to the EU-driven Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regime (SFDR). No one contests the need to hold people accountable on ESG through reporting and measurement. But they warn against introducing rules for the sake of it, which may only serve to add obstacles to the path from company-level disclosure to LP-level reporting.

Corporate governance in Asia Pacific is an example of what not to do, according to Blackpeak's Leahy, where real insight has been sacrificed in favor of top-down, regulator-driven disclosure. ESG might also be pushed out of the boardroom into the hands of passive compliance units if overregulation persists. "There's a risk of missing the wood for the trees, spending too much time bogged down in checklists and paperwork, and missing the opportunity to implement material change," he says.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.